Exclusive: Pittsburgh Schools Reported Zero Student Arrests While Court Records Show It’s a Discipline ‘Hot Spot’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Zero. That’s how many Pittsburgh students were arrested at school during the 2017-18 academic year, according to the most recent federal education data. Certainly that’d be something for the 20,000-student district to celebrate, but there’s just one problem.

It isn’t true.

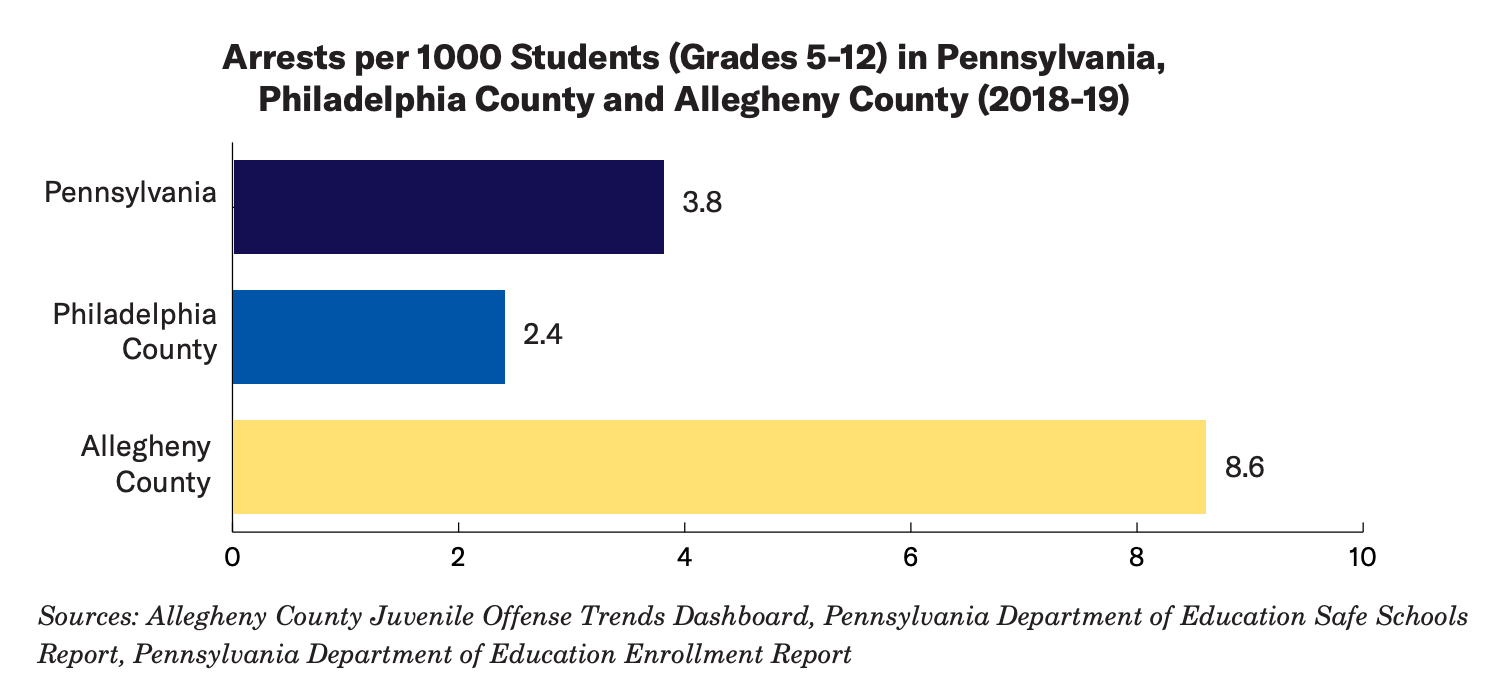

In fact, county juvenile court data tell a completely different story — one in which police actually carried out nearly 500 arrests in Pittsburgh schools that year, disproportionately against Black students and children with disabilities, often for minor offenses. That’s a key revelation in a study released Wednesday by the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, which found that school districts in Allegheny County had dramatically underreported interactions between kids and cops to the U.S. Department of Education. Student arrest rates in the county exceeded the state average, the ACLU analysis found, and among the county’s 43 districts, Pittsburgh Public Schools played an outsized role in shuffling children from campuses into the criminal justice system.

The underreporting combined with the high student arrest rates, the report argues, raise serious questions about whether Black students and those with disabilities, who are disproportionately subjected to school-based arrests in Pennsylvania and nationally, receive “the protections from discrimination guaranteed by law.”

School leaders “have to realize that connecting young people to the justice system is harmful” and understand that “how educators choose to deal with students is a responsibility that they have,” said report co-author Harold Jordan, the nationwide education equity coordinator at the ACLU of Pennsylvania.

“The conversation is really about the harms to Black children” Jordan said, and while the Pittsburgh district “does not want to be seen as anti-Black or insensitive to the concerns of Black parents,” leaders have failed to adopt sufficient student interventions that don’t involve the criminal justice system, he said.

The Pittsburgh district attributed the underreporting of its data to the federal government to an error. After taking heat for racial disparities in arrests, school leaders hired a consulting group in 2020 to study arrest data and created a task force focused on improving school safety.

The U.S. Department of Education did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Outside southwest Pennsylvania, federal education data suggest the issue of underreporting student arrests is widespread nationally. The Education Department’s Civil Rights Data Collection is key to enforcing federal civil rights laws, but advocacy groups say inconsistencies and underreporting by local districts could weaken its utility.

School policing has become increasingly fraught in recent years, and dozens of districts cut ties with local law enforcement after a Minneapolis cop murdered George Floyd in 2020. Yet in the wake of destabilizing pandemic-induced campus closures, schools across the country have reported an alarming uptick in student misbehavior, including fights and weapons possession, and some districts have beefed up campus police to combat the mayhem.

By underreporting campus arrests, however, districts could give parents an inaccurate picture of campus safety and the effects of school-based police on the young people who interact with them.

“The harms of having police in schools are much more widespread than districts report,” said Jordan, who called Allegheny County a “hot spot” nationally for youth arrests. During the 2018-19 school year, Pittsburgh students were arrested at nearly eight times the state rate, the ACLU found.

Black and disabled youth face the brunt of arrests

Attorney Kara Dempsey, who represents children in education and juvenile delinquency matters, knows firsthand the long-lasting effects of school-based police on Allegheny County youth — especially Black girls.

In one instance, a middle school girl who said she took her teacher’s credit card as a joke ended up getting arrested, Dempsey said. Due to probation violations, she wound up in a secure detention facility. Youth often struggle to comply with probation guidelines, Dempsey said, and school-based arrests can then grow into a yearslong cycle of juvenile justice involvement.

“Because she has trauma, she runs from these facilities,” said Dempsey, a supervising attorney at the Duquesne University Youth Advocacy Clinic. “That just continues this cycle. It’s just really insane.”

Local activists have been sounding the alarm for several years. In a 2020 report, the local Black Girls Equity Alliance found Pittsburgh school district police were the single largest source of juvenile justice referrals for Black girls, accounting for a third of all referrals countywide. Black girls in Allegheny County were referred to the juvenile justice system at a rate 10 times higher than white girls, researchers found.

In response, Pittsburgh Public Schools hired a consultant group, RMC Research Corporation, to study the drivers of school-based arrests. Black students accounted for about 80 percent of district arrests, RMC found in its report, but just 53 percent of the student population.

Part of the problem can be explained by the “adultification” of Black girls in which adults view them “as more culpable, less innocent and less in need of help and support” than their white classmates, said Sara Goodkind, an associate professor of social work at the University of Pittsburgh who helps lead the equity alliance’s juvenile justice work.

“These really high rates of referrals of Black youth are not because there’s a problem with young people. It’s that there’s a problem with the adults who are responding to them and with the systems we have in place,” she said.

The number of police officers stationed inside public schools has grown exponentially in the last few decades, and research suggests their presence precedes an increase in student arrests. More than two-thirds of public middle and high schools had at least one school-based officer during the 2017-18 school year, according to the most recent federal data, and while suspensions and expulsions have declined in recent years, arrests have grown.

Police presence has long been bolstered by high-profile yet statistically rare mass school shootings, yet research is mixed on their ability to improve campus safety and civil rights groups have often warned their presence could do more harm than good.

To better understand student arrests in Pittsburgh, ACLU researchers analyzed data reported to the federal and state government, as well as internal district figures obtained through public records requests and those produced by the RMC Research Corporation. The results were perplexing, Jordan said, because each source produced different numbers.

During the 2017-18 school year, the Pittsburgh district reported 86 arrests and 395 law enforcement referrals to the state education department. That same school year, the district reported zero arrests to the U.S. Department of Education while the county juvenile court tallied 499 school-related arrests.

“For a district in which the arrest rates have been high for a very long time, why should they be so inaccurate,” Jordan asked. “I can’t speak to intentionality, but they are in the position to know that what they have put out to the public is inaccurate. They are well aware of that.”

During the 2017-18 school year, Black children made up 15 percent of the country’s students but 31.6 percent of those reportedly arrested at school, according to the most recent federal data. Black students with disabilities accounted for just 2.3 percent of the total student population but 9.1 percent of those subjected to arrests.

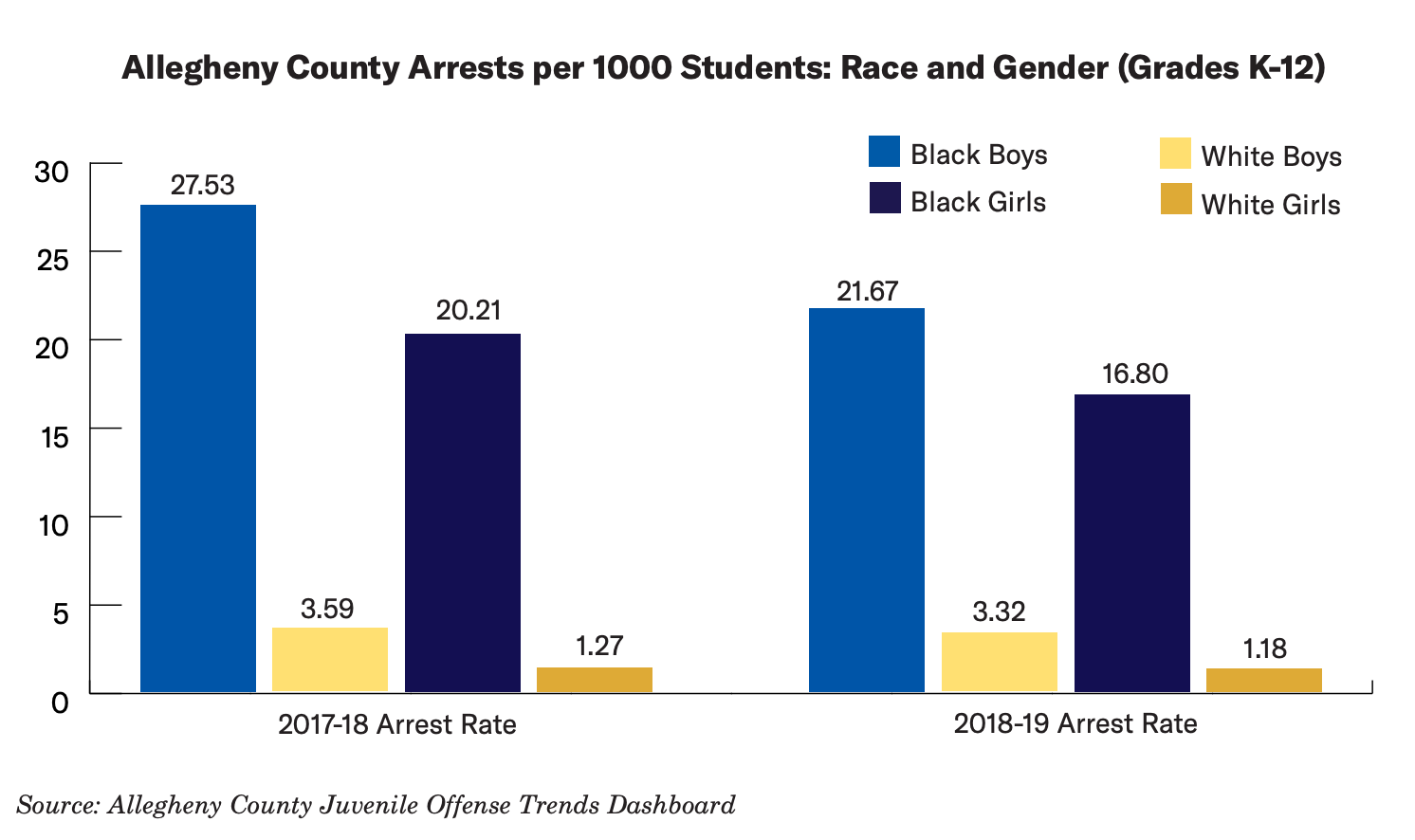

In Allegheny County, the racial disparities were far starker: During the 2018-19 school year, Black students were arrested nearly nine times more often than their white classmates, according to juvenile court records. That year, 1 in 51 Black boys and 1 in 69 Black girls were arrested at school compared to 1 in 316 white boys and 1 in 894 white girls. Black girls were the only demographic group where more than half of juvenile arrests stemmed from school incidents.

“The numbers speak from themselves,” Dempsey said. “There’s obviously bias in decision-making from people in power who have the ability to decide whether to either charge these individuals or not.”

Racial disparities were most severe in the 1,500-student South Allegheny School District, where a quarter of Black middle and high school students were arrested during the 2017-18 school year.

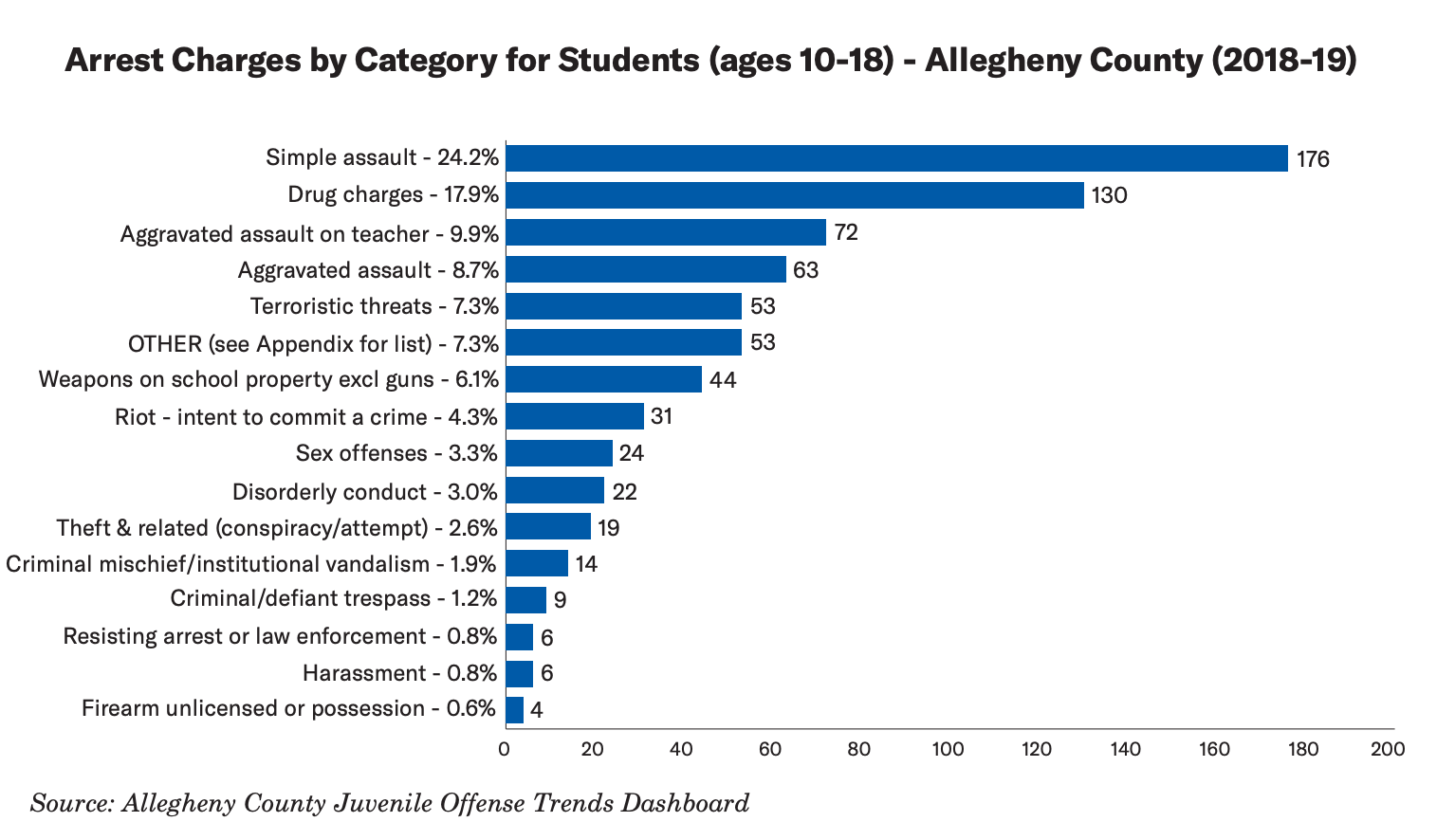

ACLU researchers found about half of arrests countywide were for simple assault or for drug charges, primarily involving small amounts of marijuana.

The drivers of racial disparities in student arrests and other forms of discipline, including suspensions and expulsions, have long been the subject of research and passionate debate. One study, published in 2020 in the academic journal Social Forces, attributed nearly half of the discipline gap between Black and white students to actions by teachers, suggesting that the “differences in punishment may be due to racial bias.” Just 9 percent of the disparities could be explained by differences in behaviors between Black and white children, researchers found.

Ted Dwyer, the Pittsburgh district’s chief accountability officer, said in a statement the arrest data it reported to the Education Department was inaccurate “due to an employee illness” that hindered fact-checking but didn’t learn about the problem until it was too late to submit a correction. He said the district has worked to improve data reporting processes, including those related to student arrests.

Dwyer said school police “have demonstrated their commitment to working with the school staff to curtail arresting students,” and noted that arrest rates have dropped in the last several years. However, he said arrest rates have decreased more quickly for white students than their Black classmates, therefore making the disparities even larger.

“The district has convened a task force to conduct deep listening sessions, review of the School Safety Manual and evaluate the effectiveness of current school safety and well-being,” he said in the statement. “The group continues its work.”

Questionable zeros reported nationally

By matching education data to juvenile court records, Jordan and his co-author Ghadah Makoshi, a community advocate at the civil rights group, took an unconventional and labor-intensive approach to expose the extent of school-based arrests across Allegheny County. School districts don’t generally compare their data against the figures collected by juvenile courts, Jordan said.

On a few occasions, journalists have done similar investigations. In a 2016 analysis of court records, The Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky, found that the local school district failed to report hundreds of arrests to the state. In 2020, Illinois Public Media reporters found that districts across the state had underreported student arrests to the U.S. Department of Education for years.

The issue plagues districts across the country. More than 60 percent of large school districts reported zero school-related arrests during the 2015-16 year, according to a report released in 2020 by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, a figure that suggested “a widespread failure by districts to report data on school policing despite the requirements of federal law.”

Three of the country’s 10 largest school districts — including those in New York City and Chicago, reported zero student arrests during the 2017-18 school year, according to a recent analysis by the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit news outlet. Yet in New York City, for example, police department records surfaced some 1,200 campus arrests that year.

For years, the federal Civil Rights Data Collection has faced scrutiny for offering incomplete data on highly sensitive topics other than school-based police, including on instances of sexual misconduct and educators’ use of physical restraints. In a 2020 report, the Government Accountability Office found that 70 percent of school districts reported zero seclusion and restraint incidents during the 2015-16 school year but the U.S. Department of Education lacked tools to fact-check the data’s accuracy. The department’s quality control processes, the government watchdog found, were “largely ineffective or do not exist.”

Advocates combating sex-based discrimiation have long accused districts of underreporting campus misconduct. In an analysis of federal civil rights data from the 2015-16 school year, the nonprofit American Association of University Women found that 79 percent of public schools serving students in grades 7 to 12 reported zero incidents of sex-based harassment or bullying.

Given the data’s role in enforcing civil rights laws, Jordan said the U.S. Department of Education should be more aggressive in ensuring the numbers are reliable. With better data, he said, researchers can better understand the impact of police in schools.

“The data doesn’t answer the whole question,” he said, “but it gives you the opportunity to drill down, to see what can be changed to improve the overall school environment without involving police and the criminal justice system.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)