Exclusive: Decade After Damning Report, Minneapolis Still Fails Special Ed Kids

25% of students with disabilities were proficient in reading in 2014. The district vowed to fix it. Now, it's 21% — and 18% are at grade level in math

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In 2014, Minneapolis Public Schools commissioned a review of its special education programs. The resulting 46-page report was packed with data pointing to an overarching, damning conclusion: The district had a systemwide literacy crisis. Until it was able to teach all of its challenged students to read, children with disabilities would necessarily lag.

At that time, about 25% of special education students were literate, as measured by state reading assessments, even though research suggests 75% of children with learning differences are generally capable of performing at grade level.

The report contained a number of recommendations and a warning: The needed changes “would typically take 1-3 years of careful planning, research, communication, coordination and roll-out, with a commitment from the leadership to provide focus and stability during the implementation process.”

The school board demanded bold change, and district leaders promised swift attention.

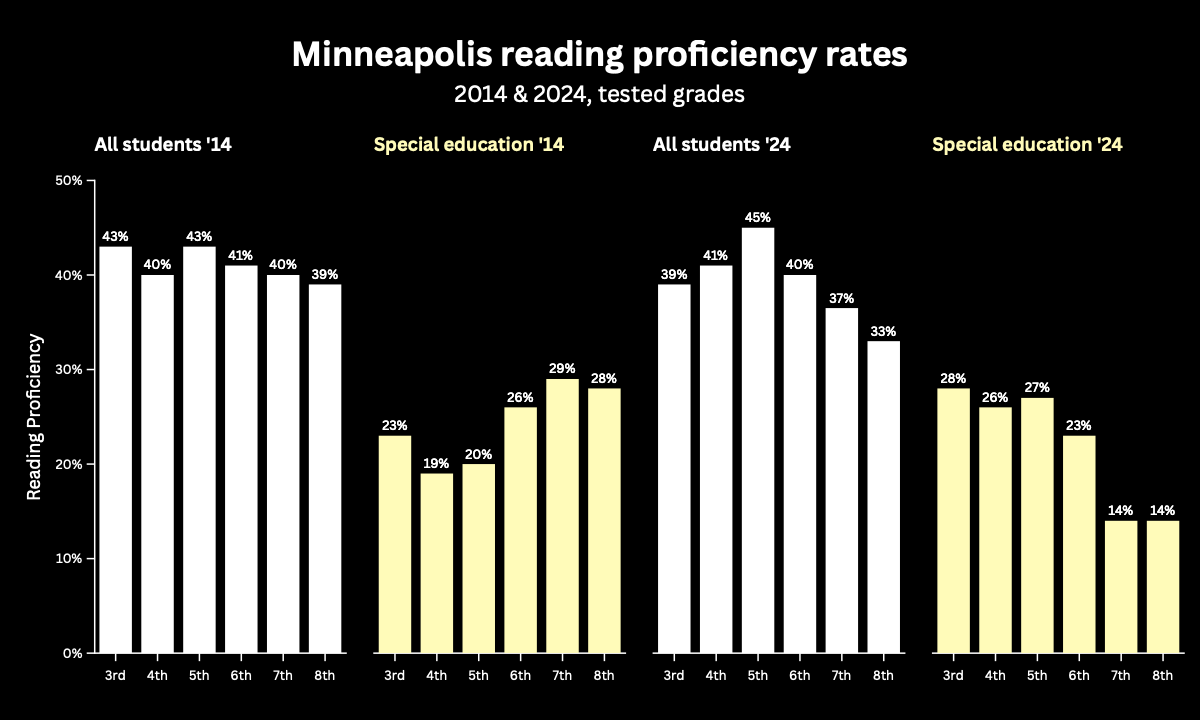

Fast forward not 1 to 3 years, but a decade. A new review from the Council of Great City Schools finds that Minneapolis schools still don’t provide adequate, equitable programming for children with disabilities. A copy of the report obtained by The 74 reveals that 11 years later, the number of children with disabilities who are literate has fallen to 21%.

A key reason: a continued lack of solid instruction — this time, in both math and reading.

Children who were kindergartners in 2014 are about to start 11th grade.

The new report runs to 187 pages. In the intervening decade, literacy has risen among elementary special education students and fallen in grades 6 to 12. But overall, by 2024, the number of children with disabilities who could read at grade level had fallen to 21% and the number proficient in math stood at 18%.

District leaders have had the review since April, but have not released it publicly — something that has caused ripples on private social media accounts within the city’s disability community. It is now scheduled for public discussion at a special meeting of the board Aug. 12.

Minneapolis Public Schools did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The new report flags many of the same problems as the 11-year-old review, finds math instruction and behavior interventions are haphazard and recommends an extensive reorganization of special ed staff and programs. Among the findings:

The district fails to provide grade-level lessons for many children with disabilities, segregates more students in special ed classrooms than similar school systems, has huge racial disparities in discipline — and little guidance for staff on constructive responses to behavior issues — and high rates of absenteeism.

In addition, special education leaders lack clear lines of authority and accountability, educator training is inadequate and the district is likely losing money because no one person oversees Medicaid billing for in-school therapies. Students who need specialized transportation come and go on dozens of unexplained, alternative schedules, driving up costs and contributing to driver shortages.

“It’s shocking, but not surprising to see it in black and white, how poor a job we are doing of serving students with disabilities,” says Maren Christenson, who sits on the board of the Minnesota-based Multicultural Autism Action Network. She is particularly disappointed that except for a couple of passing references, the report does not include the voices of special education students or their parents.

Parent literacy activist David Weingartner says the school system in fact is making strides toward getting better classroom materials and training teachers on their use. But the 2014 report’s one- to three-year timeline for improvement, he says, did not account for huge rates of leadership turnover.

“We create these reports and then we cycle through superintendents and district leaders and district staff to the point where there’s nobody to take accountability for the report,” he says. “We’re at the point now where we’re making progress. But every year of a delay, it really sets the whole district back.”

In the decade between audits, the district has had five superintendents — one of them the former director of special education — and a rotating cast of school board members. It has also lost some 20% of its students, meaning a decrease in state tuition dollars and an increase in underenrolled classrooms. This has precipitated a financial crisis that has snowballed.

For the upcoming school year, district leaders dipped into reserves to close a projected $86 million shortfall in its approximately $750 million budget. Gaps of about $100 million and depleted reserves are anticipated over the next four years.

Christenson and other advocates fear the tide of red ink that has swelled since 2014 will stymie efforts to address the issues raised in the new report. “I really wish I could be hopeful this would be a clarion call to do something differently, you know, lightning bolt or something that we should start rethinking how we’re doing things,” she says. “But I just don’t see how that’s possible given the financial circumstances that the district is in and given the environment that we’re in right now.”

A coalition of parents who have lobbied the district to change its reading instruction, the Minneapolis Academics Advocacy Group pushed the school board to use one-time federal COVID relief funds to invest in new reading curriculum and teacher training. Instead, the money was used to postpone painful decisions such as closing underenrolled schools.

The auditors several times noted that they could not open newsletters and other resources intended to help educators and community members on the district website because they were password-protected.

The reviewers also called out a lack of transparency among staff. “Special education department leadership does not openly discuss challenges with district personnel,” the report notes, “limiting the potential for improvements.”

The reviewers focused much of their attention on the district’s piecemeal use of a framework called multi-tiered systems of support — a focused strategy that involves flagging individual students struggling with academics or behavior and attempting targeted interventions. Not a substitute for special education services, the strategies are intended for use with all students.

The 2014 audit called for implementation of a similar strategy so that educators could pinpoint the reasons why individual children struggle with academics or behavior and plug those specific gaps. Both students with disabilities and their non-disdabled classmates would achieve more. Better overall outcomes can keep children who don’t need formal disability services out of special education, both reviews said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)