A New Kind of Curriculum Night: Armed With Protest Signs and Data, Diverse Group of Minneapolis Parents Demands Better Reading Instruction for Their Kids

By Beth Hawkins | September 28, 2021

So what does it look like when families storm their local school board armed with data showing not just their school system’s failures, but evidence of success elsewhere? Officials are finding out in Minneapolis Public Schools, where tensions over flagging literacy rates have built up over a decade.

For years, the proportion of the district’s Black, Latino and Indigenous students and pupils with disabilities reading at grade level has hovered between 1 in 5 and 1 in 4. Depending on demographics, at some district schools the percentage of children reading on grade level is in the single digits.

Families of color have pushed for change and, seeing little, decamped for charter schools or took advantage of Minnesota’s open enrollment law to send their kids to suburban districts in large numbers. There has been no shortage of hand-wringing about the crisis, but, as in many large school systems, the guiding belief has been that parents and policymakers should leave all things curricular to the experts.

Still, in the last year, the ground has begun to shift, as an unlikely coalition of parents has come together to challenge Minneapolis’s strategies for teaching reading. Backed by the nascent National Parents Union, Twin Cities families of color are leading the charge, representing a socioeconomic cross-section of the city that includes affluent, white district parents whose children struggle with dyslexia.

As they press their demands with district leaders — through letters, at meetings, during public comment time at school board hearings and at protests outside them — the parents come armed with a growing archive of scholarly research that suggests the schools’ literacy strategies are ineffective at best. They also know there is cash to fix them, thanks to the American Rescue Plan. And they, finally, have the district’s attention.

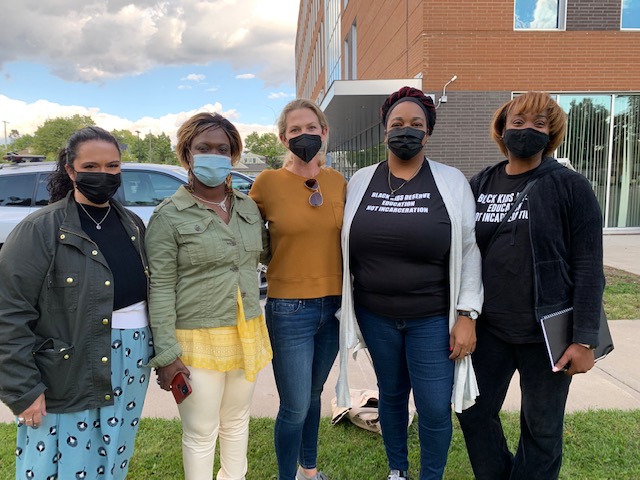

A former teacher, Khulia Pringle is a longtime Twin Cities parent activist who was tapped by the parents union to be its Midwest organizer. In September, she addressed a diverse group of families and students protesting in front of district headquarters, where the school board was about to discuss how to spend $160 million in federal pandemic stimulus funding. It was the group’s second demonstration in three months intended to pressure the district to shore up literacy instruction.

“They have major, major millions of dollars,” Pringle told the modest assembly, which included several parents union colleagues from other parts of the country. “They need to get a literacy plan that’s based on the science of reading.”

Given the pandemic’s academic losses, the school board should see the problem as more urgent than ever, said Sara Spafford Freeman, a parent advocate with a child with dyslexia. “The district has identified literacy as a priority” but seemed inclined to spend the stimulus funds on other things. The protesters needed to do “Whatever we can to convince them to pump the freaking brakes.”

Unlike in years past, the parents have statistics far beyond just the number of students who arrive at the crucial juncture of third grade reading too poorly to have much hope of ever achieving academic success. Much to the administrators’ shock, they understand why the problem is so persistent and what specific changes have sparked dramatic improvements elsewhere.

A podcast fuels a movement

Three years ago, journalist Emily Hanford published “Hard Words,” an audio documentary and accompanying article subtitled “Why aren’t kids being taught to read?” It laid out what researchers called “the settled science” of how children become literate — and the ingrained resistance of many education leaders to acknowledging the evidence.

Seemingly overnight, parents were grilling teachers and principals about their positions on whole language, the prevailing theory, which holds that children exposed to lots of books learn to read as automatically as they learn to speak. Whole language runs counter to evidence that most pupils must be taught to decode English’s odd letter combinations and sounds.

The report, along with follow-up pieces documenting teachers’ lack of awareness and explaining why colleges of education cling to discredited strategies for teaching reading — such as having students guess at a word after looking at pictures in a book — made Hanford a household name at dinner tables around the country. Suddenly, parents had a concrete understanding of why their children struggled to read, and possessed the resources to confront their school systems about it.

In August 2020, Pringle and the other parents came together as the MPS Academic Advocacy Group to pressure district leaders to change their approach to teaching reading. Right out of the gate, they had a long and diverse list of supporters, many of them parents of differing socioeconomic statuses who had assumed it was just their child who struggled. Some had believed poverty, not inadequate instruction, was the major hurdle to better academic achievement. But then, these parents from various income levels and disparate corners of the city compared notes.

They began corresponding with district leaders and after several months were told a new literacy plan would be forthcoming this past May. When the school board met, however, what Superintendent Ed Graff presented was a vague “framework” for how a plan would be developed. The families organized their first protest for the following board meeting.

District leaders declined to comment for this story. But at school board meetings over the winter, Graff defended the district’s balanced literacy approach — a common method developed in response to researcher criticisms that mixes existing lessons with some phonics instruction — while acknowledging the need to address flagging reading rates. In particular, he has rebuffed parents’ complaints about the reading curriculum the district adopted four years ago.

— Khulia (@kahlilahx1234) September 20, 2021

Morgan Polikoff, a professor at the University of Southern California Rossier School of Education and author of a book on curriculum reform, says the unusual thing happening in Minneapolis is that while school administrators all over deal with constant complaints, the Twin Cities parents have evidence.

”It doesn’t surprise me that the administrators are not prepared to defend themselves,” he says. “In the ed schools these educators attended, it’s probably generally accepted that balanced literacy is the better way to do things. They’ve never had to defend these things.”

For years, Minneapolis schools did not have a literacy curriculum at all. Then, in 2014, an outside audit of its special education programming blamed low literacy rates among children with disabilities on the district’s overall failure to teach all students to read. In the wake of that report, and following a pilot program that resulted in impressive student growth, the district paid $1.2 million for a curriculum called Reading Horizons.

A scandal erupted even before the materials could be distributed to classrooms. No one, it seemed, had vetted some supplemental materials that were included under the contract, and the classroom library books included offensive stories. In one, an African girl named Lazy Lucy struggled to keep her hut clean. In another, a Native American child and her father hunt a woolly mammoth.

After community outcry, the district scrapped the curriculum and Graff, newly hired in the aftermath of the scandal, spent $9.5 million on a balanced literacy curriculum called Benchmark Advance. More recently, the district purchased materials to supplement the curriculum for students who still struggle to read.

When Hanford’s “Hard Words” was released in 2018, David Weingartner, a Minneapolis Public Schools father who had paid for private reading instruction for one of his kids, took note. Once the chair of a state-mandated district committee focused on issues including third-grade reading, he knew better than most wealthy parents how few options his less affluent neighbors have. The committee had, several times over the previous eight years, urged district leaders to adopt evidence-based literacy strategies, and last year called for an audit of both its core curriculum and its reading intervention programs.

But with pandemic learning losses looming, Weingartner and Spafford launched the MPS Academics Advocacy Group and invited Pringle to loop in the primarily low-income Twin Cities parents of color she works with. They built a website and uploaded data, charts, graphs and parent testimonials, as well as information outlining how other states, districts and community advocates have addressed problems with balanced literacy. They also invited advocates from other school systems to virtual meetings about their efforts to get their districts to adopt evidence-based reading curriculum.

More than 20 states have adopted laws banning balanced literacy and requiring districts to adopt high-quality curriculum or train teachers on the science of reading. One of the first was Mississippi, which in 2013 passed a comprehensive literacy law credited with generating the only rise in reading scores on the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress. Several low-income districts in Delaware saw rapid improvement in reading rates after adopting evidence-based literacy curriculum, as has Baltimore. Louisiana and Colorado also have state-level efforts identifying quality classroom materials and giving districts incentives to adopt them.

By contrast, Minnesota law prohibits the state from mandating any particular curriculum, though it does require school systems to use evidence-based literacy instruction, screen students for reading disorders and report the results, along with information on interventions used to bring kids up to speed. Teachers colleges must train educators accordingly.

The state’s inability to intervene is problematic, says Polikoff. “Public schools are a creation of state governments,” he notes. “They only exist because of public money.”

Minnesota schools where more than 15 percent of students need extra reading support are supposed to consider whether their core instructional materials are ineffective. The Academics Advocacy Group has asked Minneapolis district leaders to detail how they are complying with the state requirement to report the number of students receiving interventions.

With less than half of district students reading at grade level before the pandemic, Weingartner says, parents are sure the number of children who should be getting interventions is high. But district leaders have not provided statistics to either the parents or The 74 or responded to concerns that one of the main interventions does not conform to the science of reading.

The district uses Fountas & Pinnell’s Leveled Literacy Intervention, which as recently as two years ago was one of the five most popular literacy programs in U.S. schools, though an Education Week analysis showed it does not conform to the science. In California, the Berkeley Unified School District recently settled a class-action lawsuit in part by agreeing not to use Leveled Literacy and another popular program disproven by EdWeek, Reading Recovery, barring exceptional circumstances.

‘We were ghosted — that’s the only term to describe it’

Tensions over Minneapolis’s loyalty to balanced literacy flared at a December 2020 board meeting where district leaders gave a presentation on reading instruction. Director Josh Pauly, a former district teacher, questioned the superintendent and his academic team, noting that even Lucy Calkins, a Columbia University reading expert and author of a widely used, non-science-backed curriculum, had declared that “balanced literacy needs rebalancing.”

Graff dismissed the debate as a “philosophical conversation.” “This is an age-old debate, for some of you who were born before 1987,” he said, in an apparent reference to Pauly’s age. Pantomiming stabbing himself in the heart, Pauly persisted.

Next, he asked about an internal survey that showed many teachers were not using the core curriculum, were not meeting the minimum requirement for class time spent on reading instruction and professed not to know what balanced literacy is. Graff replied that the data was “a snapshot,” not representative of the district as a whole.

In April, after word of the district’s share of the federal stimulus funds became public, Pringle started meeting with families for input on how it should be spent. Literacy emerged as a top priority. Even if the district hadn’t been able to afford new reading materials before, the parents reasoned, it had money now.

District leaders promised to present a plan at the May board meeting, but instead introduced the framework for creating a plan. In June, the parents group organized their first protest outside district headquarters, carrying signs bearing the superintendent’s face.

Their second protest came in September, before a school board meeting attended by several of Pringle’s National Parents Union colleagues. Pringle and Spafford Freeman spoke, asking the board to invest some of the pandemic aid in proven literacy materials and corresponding teacher training. But they left disappointed. District leaders proposed some $1.9 million in literacy-related expenditures, according to their presentation at the board meeting, while $75 million — almost half of the most recent stimulus allotment — would go toward staving off layoffs and program reductions necessitated by pre-pandemic enrollment losses. Another $7 million would pay to recruit and retain bus drivers and custodians.

“The asks remain exactly the same as they were a year ago, and they remain unanswered,” says Spafford Freeman, adding that she can’t believe the parent testimonials the advocates sent to board members failed to move them.

“The first time my son said to me, ‘Mommy, I think I’m stupid’ was after school on a snowy December day in 2018,” her own statement read. “My son entered 2nd grade still reading at a beginning kindergarten level.”

“You couldn’t read these letters and ignore them, so they must have just ignored the letters,” she says. “Not one board member said, ‘We want to meet with every one of these families.’ We were ghosted — that’s the only term to describe it.”

Another protest is planned for October.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation, the City Fund, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation of New York provide financial support to the National Parents Union and The 74.

Lead Image: Khulia Pringle, center, with demonstrators at a June MPS Academics Advocacy Group literacy protest. (Josh Stewart)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter