‘Everybody is Frustrated’: Feds Probe Virginia’s Handling of Special Education

Parents and advocates say lax oversight of districts left students without meaningful services during and after pandemic-related school shutdowns.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

For more than three years, parents of students with disabilities have tried to recoup special education services their children lost when the pandemic closed schools.

In Virginia, state education officials could be partly to blame.

The federal government is investigating whether the Virginia Department of Education misled school districts about their responsibility to serve students with disabilities during school closures. The probe focuses on whether the department allowed districts to deliver services that “fell short” of the free and appropriate education required under federal law.

At the time, former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said districts still had to serve students with disabilities despite the shutdown. But Virginia’s guidance during that period said officials should “acknowledge service delivery limitations” and then make “reasonable efforts” to follow a student’s special education plan — known as an individualized education program —once schools reopened.

Districts across the state released documents saying that some services would be “functionally unavailable” because students were learning remotely and that educators would do their best to serve students online and by phone.

The state education department “provided cover to the school systems for whatever type of … remote learning or virtual instruction” they provided, alleged Reade Bush, an Arlington, Virginia, father and part of the coalition of parents that asked the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights to investigate. “There was no attempt to make it compliant for students who could not engage in virtual learning.”

Virginia is the third state OCR has investigated for its handling of special education services during the pandemic. OCR dropped its investigation in Indiana in June, 2021, saying that it had no evidence the state was denying services to children with disabilities. Another investigation in Michigan is ongoing.

The Department of Education strongly reminded all states last month of their responsibility to ensure districts follow the law and suggested that some need to tighten supervision. Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia have failed to meet the requirements of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act for at least two years, and six states, including Virginia, didn’t meet expectations this year, according to the department.

Advocates welcomed the department’s guidance. Denise Marshall, CEO of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, a nonprofit focusing on students with disabilities, said monitoring “has been sorely lacking at all levels,” but added that even when states make improvements, federal officials should take “meaningful action” when needed.

‘The system is just horrible’

The federal inquiry in Virginia is the latest challenge facing the state for its oversight of services for students with disabilities. Fairfax County parents sued the district and the state agency last fall, stating that “school-friendly” hearing officers who review parents’ complaints overwhelmingly rule against families. A federal district court dismissed the case last month, but the plaintiffs plan to appeal to the U.S Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

The state’s failure to hold districts accountable is a long-standing problem that preceded COVID, according to special education advocates. Gov. Glenn Youngkin, who made parent empowerment a centerpiece of his campaign, has pledged to improve special education, but some state board members remain frustrated.

“The system is just horrible in every which way … anti-family, pro-lawyer, pro-litigation,” Board Member Bill Hansen said during a June meeting.

Virginia has had three education chiefs since the beginning of the pandemic. James Lane, the superintendent when COVID hit, is now an acting assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Education. In that role, he recused himself from Virginia education matters and OCR hasn’t discussed the investigation with him, according to the department.

Youngkin appointed Jillian Balow to replace him. She served a little over a year before resigning in March. When she stepped down, she told The 74 that special education “is the most complex work that goes on in a state agency,” but declined to make additional comments because of the lawsuit.

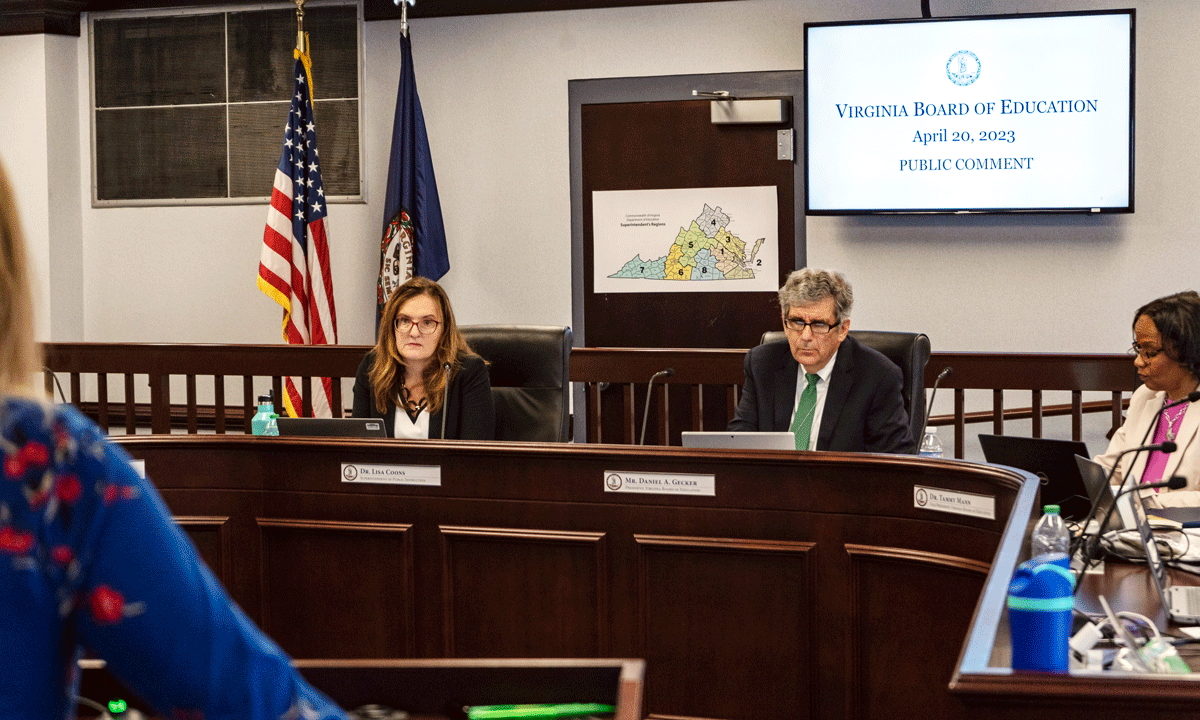

Now Lisa Coons, former chief academic officer in Tennessee, is in charge. She also declined to comment on the OCR investigation, but told the board during the June meeting that she’s making changes, such as opening a parent engagement office and taking more authority over special education.

Michael Adamson, an attorney representing the family in the lawsuit against Fairfax schools and the state, said “lack of oversight … results in a kind of Wild West” and “really bad behavior” at the district level.

‘Better off in Haiti’

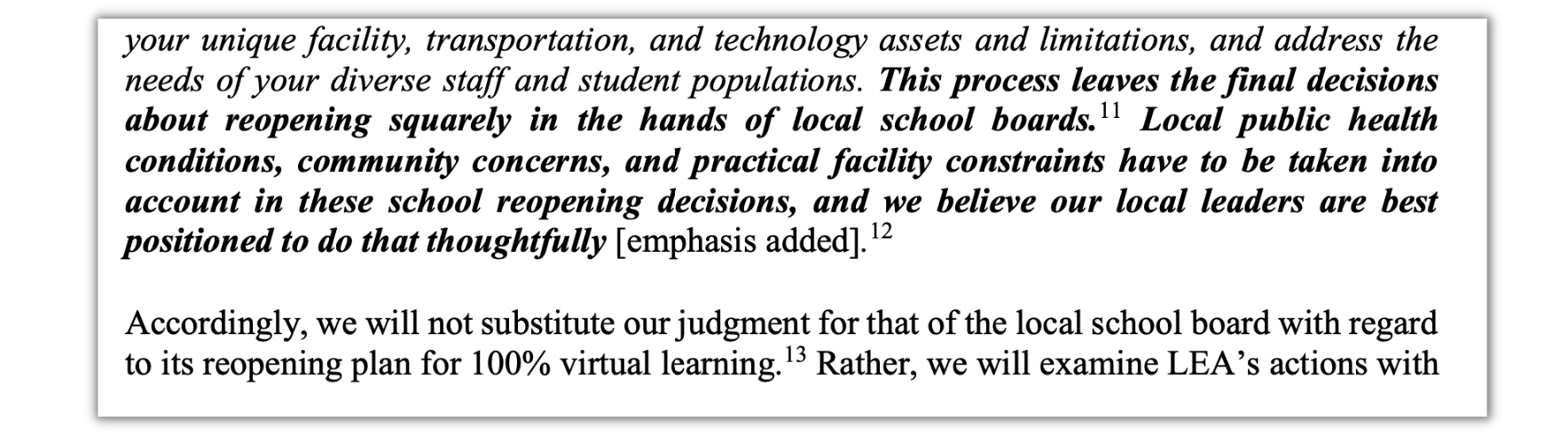

The state told a Fairfax County parent in March, 2021, that it wouldn’t override a district’s decision to only offer remote learning and that district leaders were “best positioned” to determine services. By that point, federal civil rights officials were already investigating the district’s failure to provide them.

Now Fairfax, in an agreement with OCR, must implement an extensive plan to offer compensatory education — the term for make-up services districts owe students when they fail to provide them in the first place. The district wouldn’t comment on the state’s guidance.

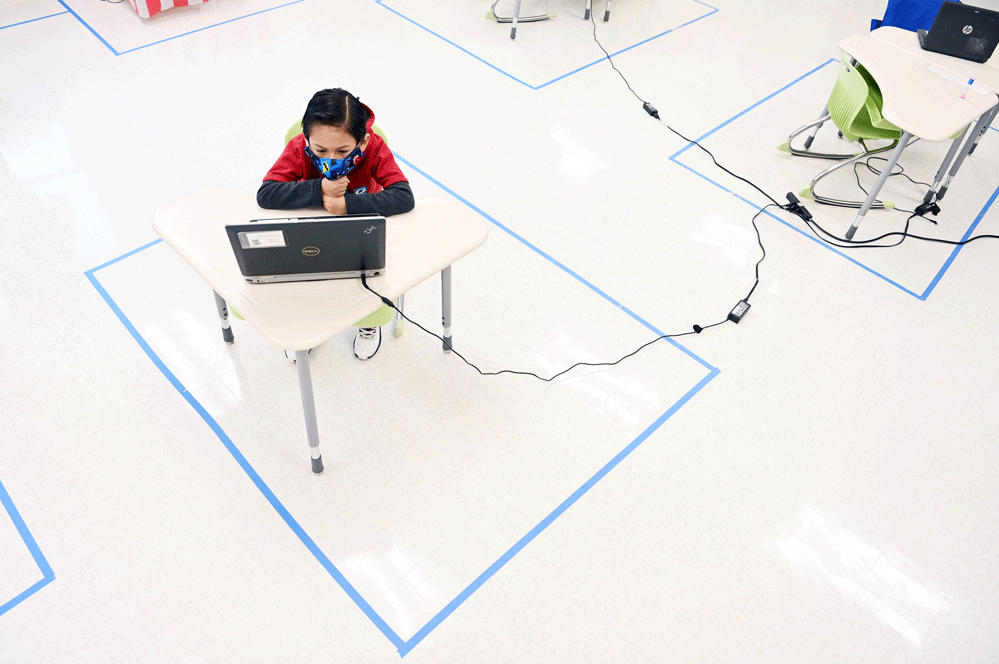

Bush and his wife, who adopted two children from Haiti in 2013, had a similar experience. His 11-year-old son, who is autistic, was among the first students that the Arlington Public Schools allowed to return to school in January of 2021. But he spent his days on an iPad, learning from an aide in another room, despite a doctor’s recommendations that he needed to interact with other children. The Arlington district did not respond to a request for comment.

Bush’s son lost reading skills, made up imaginary friends after months of isolation and, like some children with autism, began incessantly “scripting” — repeating lines from movies or TV shows. In his son’s case, it was play-by-play commentary from football games. He did hundreds of cartwheels a day and lost motivation for learning and wrestling, a sport in which he had excelled.

“He really nosedived. We’re still trying to get him back,” Bush said. “My son would be better off in Haiti of all places. They kept schools open.”

Bush and other parents continued to face opposition when asking districts for compensatory education.

His son received six and a half hours of reading support in 2021, and another 25 hours in 2022 after he showed Arlington officials test data and samples of his son’s work. Now entering sixth grade, he’s two years behind in reading.

In rural Page County, Jordan Choe’s two children, 9 and 7, have autism, ADHD and dyslexia.

During the 2021-22 school year, Choe chose to keep the children in the Page district’s optional virtual learning program. The students had access to Edgenuity, an online learning platform, but no special education services.

He complained to the state, which said in a letter to the family that remote learning “was never designed” to comply with special education law.

The family eventually hired a private tutor.

“We lived on mac and cheese and hot dogs to be able to pay for this,” Choe said.

‘Not unique’

Special education advocates say Virginia waited too long to heed the federal government’s warnings. But families in the state certainly aren’t the only ones still seeking compensatory education

“What is happening in Virginia is not unique,” said Diana Heldfond, founder and CEO of Parallel Learning, a company that provides virtual assessment, therapy and instruction for districts, including some in Virginia.

She partly attributed the breakdown of special education during the pandemic to underfunding.The law says federal funds should cover 40% of the cost of education for students with disabilities, but in reality it’s about 13%.

Students and teachers pay the price, said Anne Holton, another Virginia state board member.

“I have seen … teachers [with] …essentially no training at all dealing with some of our children with the toughest needs,” she said during the June meeting. “It’s no surprise at all to me that … everybody is frustrated, including the teacher.”

Disclosure: Andy Rotherham is a member of the Virginia Board of Education and a member of The 74’s Board of Directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)