Due Process, Undue Delays: Families Trapped in NYC’s Decades-Long Special Ed Bottleneck

Disabled children had their day in court 20 years ago and won. Now, families still wait for NYC schools to comply with impartial hearing orders

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

On December 13, 2022, Lorena Garcia got an email she nearly, reflexively deleted. It was a form letter from an auditing firm telling her the New York City Department of Education had violated her son’s rights. This was hardly news to Garcia, who for years had been battling to get the district to accommodate Vincent, who is now in sixth grade.

The boy is dyslexic and has a disorder that prevents his eyes from working together — a combination that requires intensive and specialized therapy and instruction. Since kindergarten, Garcia has toted medical records and other documentation of Vincent’s needs to meeting after meeting. But the district never found him an appropriate school, so eventually Garcia did that herself.

Now, here was an anonymous auditor confirming that despite a fistful of favorable decisions from the people who preside over special education disputes — known as independent hearing officers — the district had all but entirely failed to reimburse her thousands of dollars for Vincent’s private school tuition.

Garcia, whose name and the name of her son have been changed to protect the child’s privacy, says that at first she thought the email was fake. “It was the first time anybody ever said anything that had happened was wrong,” she says. “Everyone up until then had just been like, ‘Oh, well.’ ”

She felt a glimmer of optimism, Garcia says, but also steeled for it to be one more episode of false hope.

Special education is notoriously fraught in many school systems, but the magnitude of the problem in the nation’s largest district, New York City, boggles. The department is supposed to educate nearly a quarter of a million children with disabilities — a population that in 2019 was larger than the entire student body of all but seven U.S. school districts. In 2020-21, nearly 21% of New York City’s roughly 1 million schoolchildren received special education services, compared to a national average of 15%.

By all accounts, the Department of Education every year fails to meet even basic obligations to tens of thousands of children with disabilities. Stretching back two decades, numerous lawsuits and state audits have flagged the same problems over and over. Just this week, it was reported that 9,800 children — or close to 37% of NYC preschoolers with disabilities — did not receive all of their required services, and in March, it was revealed that 64% of bilingual special education students did not.

Because very little has changed, parents are forced — typically after years of neglect — to seek out everything from specialized instruction to intensive therapies on their own. They and their service providers are entitled to reimbursement.

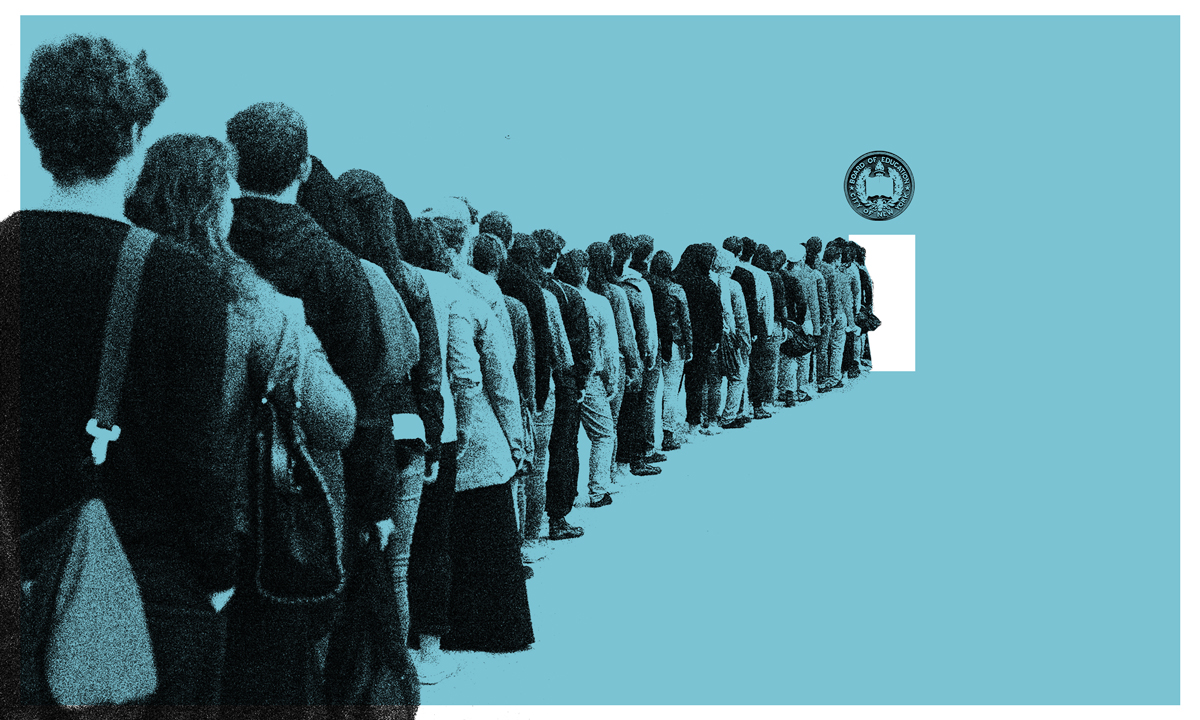

The Garcias are just one of thousands of families stuck in a narrow Sisyphean outgrowth of the dysfunction. Even with fat files of documentation and legal orders in their favor, they can’t get the department to actually cut the requisite checks. The more families who, denied services, flood into the due process system, the more bogged down it gets.

Currently, there are some 2,000 families who won their cases in front of an independent hearing officer only to have the Department of Education fail to comply with the resulting decisions.

The NYC Department of Education did not respond to The 74’s multiple requests for comment for this story. Lawyers and advocates who have followed the district’s attempts to improve its due process pipeline say it recently has added staff in an effort to clear the backlog, but basic failings persist.

The system was already at a standstill, say critics. But now, a reservoir of children whose confirmed or suspected disabilities went unevaluated and unserved during the pandemic threatens to overwhelm it completely. The department struggles to find, heat and cool, and staff enough rooms to hear waiting families’ cases, much less process their reimbursements.

Vincent was years from being born when a court first ordered the district to revamp its handling of the hearing officers’ orders. In 2003, Advocates for Children, a nonprofit that works on behalf of disadvantaged NYC children, filed a class-action lawsuit, L.V. v Department of Education, over the problems with the hearing officer system. The suit originally encompassed nine students and now includes the thousands who are essentially in the same predicament as Vincent.

“All I can say is that I have been doing this since 2012 and there’s a new problem every year,” says Bonnie Spiro Schinagle, the special education attorney who represents Garcia. “It doesn’t seem like anyone has really put organized thought into this, identified problems, identified solutions and then figured out a pathway to implementing them. They just haven’t.”

The litigation was supposed to force the DOE to begin complying more promptly with orders issued by hearing officers. There has been little progress though and in March, a special master — a court-appointed overseer tasked with tracking the district’s compliance — issued a 127-page report containing 75 recommendations and a warning: The overhaul still would take years to complete.

Unstopping the bottleneck will require such wholesale transformations, the report says, as the department moving a process that now often involves handwritten documents online and making itself a more attractive, competitive employer — not just to the special educators and therapists who are in desperately short supply — but to the administrative staff who process hearing orders and invoices.

It’s the latest in a long line of attempts to impose timeliness, responsiveness and efficacy on a system with a protracted history of being resistant to all three.

‘The reality is people have been waiting for years’

Garcia knew very little of this context when she received the December email that seemed too good to be true. The auditor, whose appointment was part of the 20-year-old class-action lawsuit, suggested that she ask her attorney to file a federal lawsuit. The email included an attachment the auditor said would serve as evidence substantiating her claim. Garcia called Spiro Schinagle, who said she was already preparing civil complaints for a number of families who had received similar emails. The lawyer added the Garcias to her list.

Well-worn federal civil rights law is clear regarding situations like theirs: If a school system can’t serve a child with disabilities, it must pay for a program that can. Vincent’s mother enrolled him at a private school in Queens serving a small number of children with learning disabilities like her son’s.

His tuition changes from year to year, but has hovered around $44,000 a year, according to court documents. If that sounds steep, it includes the cost of services school districts frequently struggle to provide in a cost-effective manner.

So far, in each school year the family has been forced to pay some or all of the tuition, pending a response from the DOE bureaucracy. Not including the 2022-23 school year, the Garcias are owed at least $27,324, plus attorney fees, according to court filings

The reality is that people have been waiting for years to get the orders to get the services their children need.

Rebecca Shore, director of litigation, Advocates for Children.

As the U.S. Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act requires, the district is supposed to serve children who need special education services along a continuum ranging from individualized help in a regular classroom to the kind of specialized placement Vincent requires. NYC students whose needs can’t be met in a typical school are often referred to District 75, a portfolio of separate DOE schools created to offer more intensive support.

When there is a disagreement about a student’s proposed Individualized Education Program — the legal document spelling out their required services — the dispute goes before a neutral arbiter. An impartial hearing officer — someone trained and paid by New York state — must be assigned within two days and the case heard in two weeks or less.

The entire process should take no more than 75 days. But Garcia’s experience of having it drag on is common.

“The reality is that people have been waiting for years to get the orders to get the services their children need,” says Rebecca Shore, director of litigation at Advocates for Children. “It’s not an issue of resources being available. It’s an issue of kids getting the services they need.”

Advocates and attorneys who represent special education families in New York City are quick to assert that the bottleneck — getting the DOE to comply with orders issued as the result of a single type of due process hearing — is a symptom of the much bigger problem.

In 1979, a group of families sued the department, alleging that it failed to obey federal laws requiring the evaluation of all children with suspected disabilities and to provide them with appropriate services. Because the system has never been able to keep up with the need, pressure from that lawsuit resulted in a decision ordering the district to pay for a private school for the children it can’t serve.

One outcome, according to Michael Rebell, a professor and the executive director of the Center for Educational Equity at Columbia University’s Teachers College, has been enough demand to fuel the creation of a large number of private schools offering specialized programs for children with disabilities.

“Because we have this gargantuan system, for years the department has had problems hiring enough teachers and offering enough programs,” he says. “There’s a paucity of services. And there’s also a large number of middle-class families who would prefer their kids go to private schools.”

Recognizing that indeed some parents might try to game the system, the rules say families must prove to an independent hearing officer that the district has left them no alternative. Unless the department appeals and wins, the hearing officer’s decision goes into effect.

There are two massive, resulting problems: A backlog of cases needing to be heard and the department’s inability to pay the parents, schools and providers who the hearing officers determine are owed money.

In 2007, Advocates for Children and the department settled L.V., which took aim only at the issues involving the hearing officer process, with the district agreeing to take a series of steps to speed things up. For the next decade-plus, an outside auditor — the same progress monitor who flagged the Garcias’ numerous unfulfilled hearing orders — periodically reported middling progress to the court.

Twelve years later, with her son entering third grade and three years of fruitless attempts to secure an accurate diagnosis and an appropriate school placement for him, Garcia asked for her first impartial hearing. She would leave one frustrating part of the special education system only to enter another.

For Garcia, the last straw

From kindergarten through second grade, Vincent bounced from school to school. Like lots of bright kids who struggle to read, he was initially dismissed as lazy, his mother says.

“He’s always been able to participate verbally and in presentations, but not able to read a paragraph,” recalls Garcia. “People kept telling me, ‘Oh, he’s not trying hard enough. He’s so articulate.’”

The boy confounded the evaluators, his mother said. The first time Garcia had him assessed, the psychologist doing the testing came out to the waiting room to say she was ending the session because Vincent could not stop crying. “She’s like, ‘This isn’t good for him.’”

He was diagnosed as dyslexic, but it quickly became apparent that specialized literacy instruction wasn’t enough to address his needs, says Garcia. Extensive testing revealed that despite 20/20 vision with glasses, Vincent was literally not seeing the right letters in the right sequence.

He had a condition called ocular motor dysfunction, which means his eyes do not track the same things. Because of this, he literally could not see lines of text. Letters appeared out of sequence and above or below the line.

His eyes needed training to work together, rather than presenting him with different, jumbled images. And he needed assistive technology — chiefly simple text-to-speech apps — to make sense of written words.

In response, his mother said the district placed Vincent in a school it operates for children with intellectual impairments, such as Down’s and Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. The program sent him back, pointing out that the DOE had misclassified the boy, placing him in a category of student the school did not serve.

But despite several months of back and forth over whether the district would accept its own diagnoses and come up with what it thought was an appropriate school, nothing happened.

For Garcia, it was the last straw. That’s when she hired her attorney, Spiro Schinagle, and started the process of having Vincent referred to a private school. In January 2020, the family sent the city education department a legal document saying that, because the district had failed to offer the child an appropriate placement, they were enrolling him in the Queens school they had found themselves.

At a cost of almost $21,000 for the spring semester — which Garcia, who works for another part of the NYC schools, paid from savings — Vincent spent the rest of the year starting to catch up at his new school. In May 2020, an independent hearing officer ordered the district to reimburse the family. But it wasn’t until this spring that Garcia got reimbursed for the 2019-20 school year.

[T]he parent had to lay out money year after year, and had to retain me, year after year, and go to a hearing, year after year. That, in and of itself, is outrageous.Bonnie Spiro Schinagle, special education attorney

With the district failing to come up with an alternative, Vincent has remained at the private school ever since. Each year, Garcia has had to demand a new impartial hearing and then wait months for it to take place. After every favorable decision, the family waits for the district to comply with the new order.

In August 2021, facing the prospect of fronting more tuition payments, Garcia agreed to a $12,500 settlement for the 2020-21 academic year — money she has yet to see.

As the orders requiring the district to pay stacked up, Vincent was placed in a category where the city was no longer disputing his placement and now owed the tuition money directly to his school. It’s unclear from court documents how much of that money the school has been paid. The school did not respond to a request for comment.

The advent of the 2021-22 school year meant the opening of yet another case. This round took until mid-April for the hearing officer to issue an order obligating the district to pay — directly to the school this time — for the year that was then about to conclude. In turn, Garcia said the school was supposed to reimburse her $4,400 she had gone ahead and paid, but said it could not because the district did not supply the school with some required paperwork.

“They knew that this child belonged in this particular school,” says Spiro Schinagle. “And the district time and time again refused to listen to its own [evaluator]…. So the parent had to lay out money year after year, and had to retain me, year after year, and go to a hearing, year after year. That, in and of itself, is outrageous.”

‘The goal of this lawsuit was to change the system’

The bottleneck that’s trapped the Garcia family is growing, according to the 2021-22 annual report of the New York Citywide Council on Special Education. In November 2021, it reported, there were more than 16,000 pending impartial hearing cases, a 34% increase from the year before. Some 9,000 cases had not even been assigned to a hearing officer.

New York City, a separate analysis found, is responsible for 96% of all of the impartial hearings requested in the state. The number of pending cases had not budged by January 2022. Attorneys and advocates predict that the COVID backlog will further overwhelm the system, as the parents of children who may not have gotten needed therapies for years file cases.

The council’s summary of the problems is straightforward: Because families still aren’t getting the services their children are entitled to, cases continue to be filed. Beyond that, there are not enough hearing officers and those that exist get delayed pay.

Some officers have untenable caseloads; one had a docket of more than 1,000 pending cases, as of January 2022. The Brooklyn facility where the hearings are held has no heat or air conditioning and no waiting areas or photocopiers.

The “next steps” identified by the special master hint at how far from resolution those basic problems may be. The department, its report to the court suggests, should form a steering committee and appoint people to oversee “the areas of people, process and technology.”

Two pages of acronyms for various parts of the DOE bureaucracy precede 75 recommendations ranging from figuring out how to put accounts payable online so outside service providers can get paid to streamlining onerous civil service rules that complicate hiring enough people to handle the payments.

The document is in fact so complicated that Advocates for Children, which represents the plaintiffs in the 20-year-old case, translated those recommendations it agrees with into plain English and put them onto a simple chart along with suggested timelines for implementation.

The judge must now decide which recommendations to adopt, and how to hold the department accountable for progress. There is no deadline for that decision.

“We need this to happen in an expeditious manner,” says Shore, Advocates for Children’s litigation director. “The goal of this lawsuit was to change the system so that families whose children were not getting services could get their needs met.”

As it stands, Spiro Schinagle says, the amount the district is spending to pay for due process proceedings just continues to climb. “I don’t know how much it would cost to really assess different categories of kids who really need to be served and to put together credible programs,” she says. “They’re hemorrhaging money… that they could have been spending on all sorts of things.”

The ongoing wrangling over the class-action suit isn’t likely to help the Garcias anytime soon. Vincent’s 2022-23 academic year started the same way as the three before it: with the DOE not paying its bills.

With the auditor’s email as evidence, the family’s lawsuit finally seemed to get the district’s attention. In May, the DOE emailed Spiro Schinagle a document agreeing to pay the school directly for the academic year that just finished and to pay for Vincent to return in the fall.

Garcia says she is still waiting on reimbursement for the settlement she agreed to for the money she laid out for the boy’s fourth-grade tuition, as well as some other payments. If the district pays everything she is owed, Spiro Schinagle says she will withdraw the lawsuit.

Meanwhile, Vincent is thriving, his mother said. He started at his new school at age 8 reading at a kindergarten level and, now finishing sixth grade, has mastered third-grade literacy. He gets occupational therapy for his eyes at school, which means he and his mother no longer have to make a weekly trip to Manhattan from the Bronx for private care.

Far from being lazy, as his past teachers suggested, Vincent works hard, his mother says, diligently doing his homework and signing himself up to be in the school play and serve on the student council.

“He’s thriving. He has friends,” Garcia says. “His school loves him.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)