Essential Cultural Knowledge or Backdoor Proselytizing? Trump’s Tweet Raises Profile of Bible Literacy Classes in Public Schools

America, it seems, is at something of an inflection point when it comes to religion and public education.

Public school students in Pennsylvania are challenging bans on distributing Bibles at lunch, and Catholic high schoolers in Vermont want to participate in a publicly funded dual credit program. Parents are seeking an end to rules that ban the use of state-funded vouchers and other private school choice programs at religious schools.

States are increasingly permitting or requiring schools to display “In God We Trust,” the national motto, in public schools. Several Supreme Court justices this year welcomed a case challenging existing bans on teacher-led prayer at school.

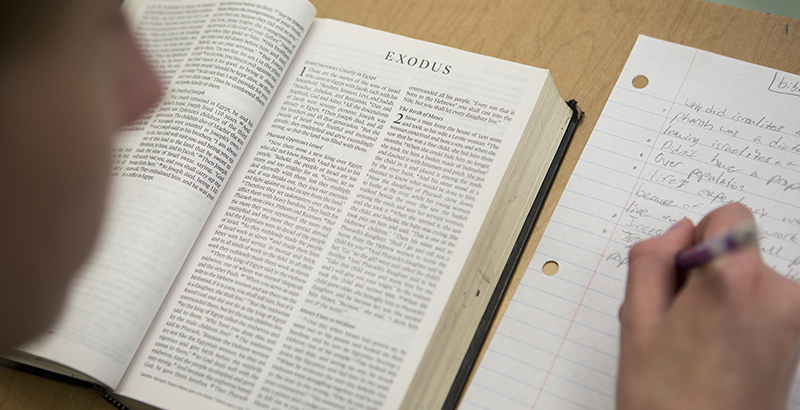

Perhaps the highest-profile of these proposed changes is a cluster of state legislatures considering Bible literacy classes. The story was picked up by Fox News and apparently caught the eye — and support — of President Donald Trump.

A measure allowing high schools to offer Bible literacy classes passed the Virginia Senate Feb. 4 and a House committee Feb. 13. A state senator in Alabama has introduced a bill before the state’s session begins in March. Bills were introduced in at least five other states this year, and Kentucky passed a similar bill last year.

The effort to pass these bills has been linked to Project Blitz, an initiative led by the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation and other Christian religious liberty groups. The groups also seek, for example, laws explicitly protecting teachers and students’ rights to practice their religion at school, and resolutions prioritizing adoptions by married heterosexual couples.

The proponents of Project Blitz position the project as one of protecting religious liberty, and they insist the Bible classes are important to students’ broader understanding of history and literature.

Bible literacy classes are a “sub-component” of general cultural literacy, said Steven Fitschen, president of the National Legal Foundation, a religious freedom group affiliated with Project Blitz.

“Our public schools ought to be educating our kids for cultural literacy, and you can’t really understand Western history, U.S. history, music, art, even figures of speech … without understanding the Bible,” he said. “We believe that it benefits every student no matter what their personal religion is.”

Groups that advocate for the separation of church and state, meanwhile, called the classes and the broader Project Blitz agenda “an alarming effort … to harness the power of the government to impose the faith of some onto everyone else, including our public school students.”

This type of back-and-forth just adds fuel to the controversy, one expert said.

“The more that people push the envelope of these types of programs and try to turn them into mechanisms for evangelism, the more you’re going to get pushback … which is then going to create the impression once again that public schools and society [are] hostile to this type of expression,” said Steven K. Green, a professor of law and religious history at Willamette University. “It’s almost a circular thing that’s going on here.”

“A turn back”?

Trump, in his Jan. 28 tweet praising the Bible literacy classes, asked whether states were “starting to make a turn back,” punctuating it with “Great!”

That desired “turn back” seems to reference a time when most schoolchildren studied the Bible in public schools, before the Supreme Court’s 1963 decision in Abington School District vs. Schempp that overturned state laws in Pennsylvania and Maryland that mandated the reading of the Bible at the start of the school day.

But that assertion, experts said, is inaccurate.

“It was widespread, but not universal, and it was often controversial. There was never a time when American schoolchildren and communities all wholeheartedly embraced and adopted this practice,” Mark Chancey, a professor of religious studies at Southern Methodist University, told The 74. “The 1963 Supreme Court decision, that was kind of the last chapter of a story that had been going for 120 years.”

The popularity of Bible reading and other devotional activities in public schools before the court’s rulings was largely dependent on region, with such activities mostly nonexistent in urban areas and in the western part of the country, Green said.

“The Supreme Court really was not the trailblazer. They were more or less responding to the transition that had been underway for many years,” said Green, who previously worked for Americans United for Separation of Church and State.

Bible literacy courses have been taught in school for years, and they were first widely proposed in the early 20th century, Chancey said.

“What is a little different now is there is a more organized, choreographed effort to introduce bills promoting conservative Christianity in public life,” Chancey said.

Academic study of the Bible in public schools is already legal, and the Supreme Court in its Abington Township decision said that “the Bible is worthy of study for its literary and historic qualities.”

It is theoretically possible for a school to teach a Bible literacy course that meets constitutional muster, but it’s much easier to teach the Bible as part of a comparative world religions or general literature class, experts said.

But some courses have gone too far by, for example, teaching events in the Bible as historical facts. (A Bible class in West Virginia, for instance, taught students that humans and dinosaurs existed at the same time. The district has suspended it amid ongoing legal challenges.)

It’s one thing to teach that Christians believe in the resurrection of Jesus, Chancey said, but “it’s another thing to teach students, public school students, that a resurrection was a historical fact.”

But it would be just as problematic for a teacher to present the Bible in a way that is dismissive of students’ beliefs, he added.

Even the specific translation of the Bible chosen as a course text can amount to a theological decision, as different sects have adopted varying translations throughout history.

Sample legislative language provided by Project Blitz emphasizes that the courses “must be taught in an objective and non-proselytizing manner that does not attempt to indoctrinate students.” It allows districts to consider courses on “the books of a religion or society other than one with Judeo-Christian traditions.”

Fitschen also pointed to provisions in the project’s sample legislation that would bar districts or teachers from requiring students to use one particular translation of the Bible, and he emphasized that the course would be elective. He rejected the idea that the Bible would be better taught in a literature or comparative religions class, arguing that there’s simply too much content in the Bible alone to cover it all.

Going forward, the status of religion in public schools — and whether or not that needs to change — depends on whom you ask.

For Fitschen, the current situation is “mixed.” Court decisions have protected student-led Bible clubs but limited school prayer, he said. The overall environment for public displays of religion in public schools is better than, say, 30 years ago, when some of those protections were established, but worse than 50 years ago, before some of the issues were litigated, he said.

For Green, meanwhile, “a mess would be the best way of saying it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)