ESSA Says State Report Cards Must Track How Many Students in Foster Care Are Passing Their Reading & Math Tests and Graduating High School. Only 16 Do

When Karina Melendez missed multiple days of school during the winter of her sophomore year, it wasn’t because she was willfully truant or lazy. The student, who usually got straight As, had been placed in the foster care system and was balancing class at her Bronx public high school with court appointments, meetings with lawyers and social workers, and the emotional shock of uprooting her life.

Melendez’s grades dropped during that time, but she was eventually able to bring them back up, graduate on time, and head to Columbia University — despite remaining in foster care through the rest of high school. Now 25 years old, Melendez credits that to the stability she found in school and the support of teachers who knew what she was going through.

But not every student who enters the foster care system receives that kind of support. Unlike Melendez, many change schools, falling months behind academically. These students are more likely to be expelled and less likely to earn a college degree. District and school leaders don’t always know who is in foster care, leaving students to struggle with trauma, mental health issues, and missed classes on their own. Historically, little data has existed to show how students in foster care perform in each district or state.

To help address some of these challenges, the Every Student Succeeds Act, passed in 2015, mandated some changes to support students in foster care. This year, for the first time, all states are required to report how well students in foster care are performing on state tests and how many are graduating from high school. These data points are supposed to be shared publicly on states’ annual report cards. But right now, only 16 states are sharing both of these data points, according to The 74’s analysis of available report cards from every state and Washington, D.C.

“It’s unfortunate, I think, that it took a federal mandate to get states to shine a light on these students, but the good news is that now it is required,” said Brennan McMahon Parton, director of policy and advocacy at the Data Quality Campaign. “That said, this information about students in foster care and their academic performance, while we think is an easier collection than some of the other new requirements in ESSA, is still new, so states are still grappling with bringing it online, making sure that it’s quality, that it’s accurate.”

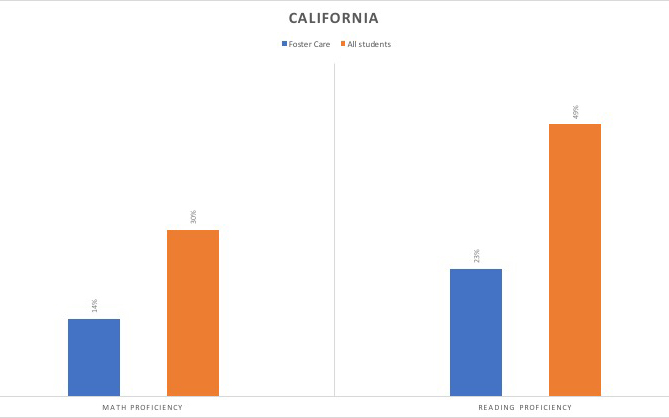

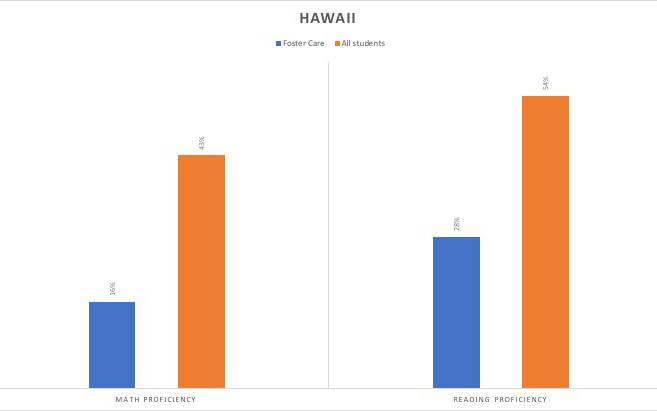

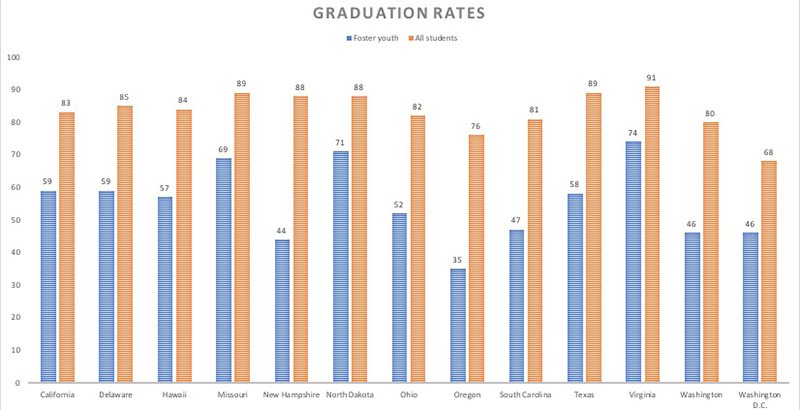

As of Feb. 15, graduation rates and test scores for students in foster care are noted on report cards in California, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Washington, D.C.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the other states are not compliant with federal law. Under the Obama administration, ESSA accountability rules required states to report these data points by the end of 2018. But in 2017, Congress eliminated these regulations, meaning that states simply have to report that information on their annual report cards sometime.

Most states released their report cards in December and January, but the majority didn’t include all the required data points on students in foster care. On some state report cards, the data for those students were technically publicly available but difficult to track down or decipher from a coded spreadsheet. Other state officials said data for students in foster care will be added sometime later this year.

The 74 reached out to 51 state departments of education to ask when they were planning on releasing the data and what the challenges were in reporting. States listed several issues, from the need to verify data and take more time to track graduation rates to challenges aligning the education data systems with their states’ child welfare agencies.

In Utah, the State Board of Education is delaying releasing data on students in foster care until the fall. “The ability to include students in foster care, homeless and military-connected students as student groups in the school report card has been built into the Utah school report card, but due to issues gathering reliable data, we have not activated those elements,” Darin Nielsen, assistant superintendent of student learning, wrote in an email to The 74. “We are working through the barriers to ensure the data we need to display is reliable and accurate.”

Foster care data were delayed in Arizona because of a miscommunication about what information needed to be collected. Schools were tracking how many parents were foster parents rather than how many students were in foster care, according to Stefan Swiat, public information officer at the Arizona Department of Education. There’s no timeline on when the data will be released. “The Accountability team doesn’t want to post the data until it’s been further vetted,” Swiat said.

ESSA doesn’t specify how states should find out which students are in foster care, but most are trying to create a data-sharing agreement with their state’s child welfare agency to determine which students are in foster care at any given time. But protecting student privacy while sharing data is difficult on both the technical and legal sides.

Some experts aren’t surprised that the process is taking so long.

“From our experience in working with states, doing that data match isn’t easy to do. It takes a lot of time, often longer than expected, and requires getting the right people to the table,” said Kristin Kelly, senior attorney at the American Bar Association, who works on the Legal Center for Foster Care and Education project.

Others argue that states shouldn’t need more time to report data points that were mandated by federal law four years ago.

There’s also an issue with how the information is being presented — sometimes in hard-to-find, separate documents apart from other subgroups like race, gender, and disability. ESSA requires that report cards be “concise” and accessible to parents and the public, but it doesn’t give much guidance as to what this means.

“It should not take a degree in statistics or 45 clicks in pursuing an Excel chart to find the answers,” said Phillip Lovell, the vice president of policy development and government relations at the Alliance for Excellent Education. “If it’s hard to find … then we’re really doing a disservice to parents and the public by not providing them the information that federal law is intending for them to have.”

For example, say you want to find out how many students in foster care in Oregon are proficient in reading. You head to the state Department of Education’s website. On the first page is a link for “Profiles and Reports.” You click on it and are led to a page that allows you to click on the state report card. You select that link and are led to another page that allows you to view a PDF of the most recent report card. You open the PDF and can find out how other subgroups are doing — like those who are economically disadvantaged or students with disabilities — but you can’t find data on students in foster care.

Instead, that information is located in a spreadsheet under a “New ESSA Student Groups” tab on the website’s “Accountability Measures” page. Oregon is technically reporting the information required by law. But it requires a lot of digging and false turns to get there. (A spokesperson for the department did not respond to a question about why the data were presented in this manner.)

Anne Hyslop, assistant director for policy development and government relations at the Alliance for Excellent Education, has seen many states turning to fancy, redesigned report card websites that may look user-friendly but don’t contain the more complex information they are required to present, such as a detailed list of the performance of student subgroups. Instead, they are buried in attached spreadsheets, obscuring the outcomes of students who need the most attention.

“Whether that’s students with disabilities, English learners, students in foster care, these are more vulnerable populations that face unique challenges, and so it’s really important to know precisely how they are doing, because there may be particular interventions or particular responses that a state or a district or a school could take for those students,” Hyslop said.

Although there’s no requirement that a report card follow a specific format, “we encourage them to be as simple and navigable as possible for parents and the public, because that’s who we know needs to access the information,” a U.S. Department of Education spokesperson said.

The spokesperson said states have not alerted the department to any issues involving collecting data on students in foster care. The department doesn’t look at every state report card every year, but it surveys a sample of them. If a state isn’t reporting data required by ESSA, “our first step is to work with the state to address whatever the issue is,” the spokesperson said.

Just because a state hasn’t reported the information on its report card doesn’t mean it isn’t publicly posted somewhere else. For example, Colorado hasn’t yet reported on the graduation rates of students in foster care, but it has conducted multiple years of research and released legislative reports on graduation rates for these students. The state’s Department of Education is following a different method of calculating graduation rates than that used by the legislature, said Director of Communications Jeremy Meyer.

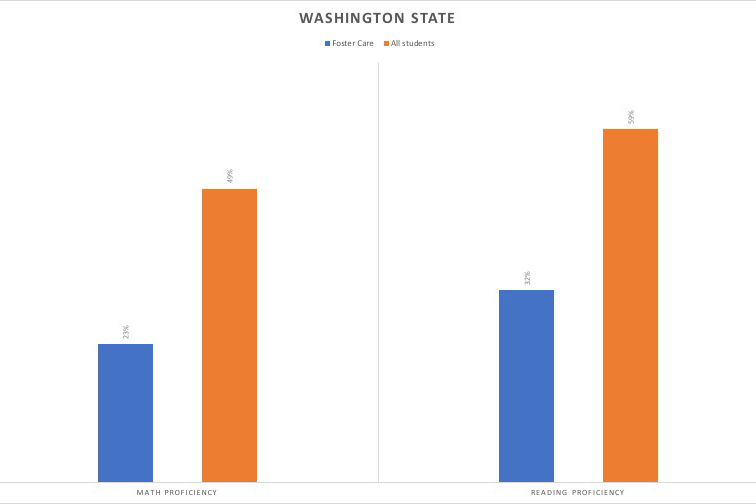

In Washington state, where the data are clearly visible on the state report card, the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction has spent several years setting up a data-sharing agreement with the state’s child welfare agency to more accurately track students in foster care. Every night, data between the two agencies are updated so that school district liaisons can see within 24 hours which students in their district have been placed in care. That way, they can quickly connect students with counselors and make sure they’re staying afloat academically, said Peggy Carlson, the Foster Care Program’s supervisor.

Before this agreement was put in place, the state’s education department had to rely on the child welfare department notifying schools when a child was placed in foster care, but this didn’t always happen, Carlson said.

In Washington, 46 percent of students in foster care graduated from high school, compared with 80 percent of all students in the state. There is no federal definition of what constitutes a student in foster care, but in Washington, any student placed in care during his or her time in high school counts toward the four-year cohort graduation rate, said Katie Weaver Randall, director of student information for the state.

North Dakota also has a data-sharing agreement with its state’s child welfare agency. To maintain privacy, a district administrator is notified when a student is placed in foster care but is not told the reason why, said Anne Linden, assistant director in the Office of Educational Equity and Support in the North Dakota Department of Public Instruction. Linden, who has been a teacher and a foster parent to 11 children, said she sees the value of federal education laws paying attention to these students. “I personally believe it’s an excellent program supporting the stability of children in education,” she said.

Some advocates for students in foster care, including Melendez, who was once in those students’ shoes, said sharing data is important but worry that the information can be misused. Specifically, Melendez fears that students in foster care will be seen as not capable academically and will be tracked into lower-level classes.

But some want policies to go beyond just data sharing. Brenda Triplett, the director of educational achievement at Children’s Aid, a child-welfare nonprofit in New York, would like to see states take action on the information they are collecting.

“Data just to collect and track, quite frankly, to me is moot unless there is a plan for evaluating and analyzing and addressing what the data is showing,” Triplett said. “Yes, we need to track, we need to have the numbers, but I don’t want this to be another empty mandate.”

Triplett recommended that states, schools, and districts support policies that help students in foster care, whether through intensive tutoring, mental health counseling, or a pathway to graduation that makes the most sense for the student’s situation, such as completing a portfolio of work rather than having to pass an exit exam.

Melendez said she hopes other students in foster care can receive the same compassion teachers in high school showed her.

“Being flexible in giving students the opportunities to catch up, to make things up, to do better and perform better and improve in their classes — that human understanding and empathy goes a long way,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)