Emanuel Confident That Chicago’s Universal Pre-K Program Will Live On After His Exit, but Will Next Mayor Balk at the Price Tag?

The abrupt announcement last week that Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel isn’t seeking re-election has raised questions about whether his sprawling initiative to implement free, universal pre-K will survive once he’s left office.

Emanuel, who continues to champion the program’s four-year rollout, is confident it will continue under the next mayor. Early education’s momentum, combined with a favorable political climate and the past year’s foundational work, guarantee its success, he told The 74.

“I believe, mark my words, that every [candidate]” will get the question, “Are you going to fulfill the next three years of universal, full-day pre-K?” Emanuel said. “And I guarantee you that all of them are going to say ‘Yes.’ Because that’s what the public wants. … It’s what our kids need.”

But not all ed-watchers are as optimistic as Emanuel. While it’s unlikely a successor would oppose free pre-K outright, some education pundits said that at a time of fiscal strain, a post-Rahm mayor may question the expansion’s $175 million annual price tag. The city’s behemoth school district, Chicago Public Schools, is already spread thin, shouldering hefty debt, educator shortages, and a half-empty teacher pension fund.

“Are they going to make sure $175 million goes to make this happen versus all the other huge financial demands that there will be?” asked Geoffrey Nagle, president and CEO of the Erikson Institute in Chicago. “That remains to be seen.”

Shoes to fill

In late May, Emanuel introduced a plan to roll out universal pre-K — in this case, preschool that’s free and eligible for all — with the goal of serving 24,000 4-year-olds annually by fall 2021. It would more than double the city’s pre-rollout capacity of about 11,000 kids during 2017-18, according to the mayor’s office.

Officials expect to have space for more than 3,700 kids to enter full-day pre-K this year. This first phase targets children from households making about $46,000 or less a year.

Jump-starting students’ education with pre-K “is Chicago’s model,” Emanuel said. “That’s the model we set.”

The program was the logical next step for a mayor who considers education an integral part of his legacy. Emanuel controversially lengthened the city’s school day, instituted full-day kindergarten, and has increased capacity for full-day, public pre-K by about 75 percent during his seven-year tenure.

Chicago’s push for early education is playing out against a national backdrop of growing public support for pre-K and research touting its importance. Quality pre-K boosts kindergarten preparedness, shrinks achievement gaps, increases high school graduation rates, and is considered a good financial investment, experts say.

Still, free universal programs are less common than those targeted only at low-income students, as they require sustainable funding streams and strong advocates. For Chicago, it will cost $175 million a year by 2021 — on top of the more than $320 million the city already invests in students from birth to 5 years old, according to the mayor’s office.

Funding stems from state allocations and grants, federal Head Start dollars, and appropriations from the city and Chicago Public Schools’ (CPS) budgets. The expansion is also part of CPS’s $1 billion capital improvement plan.

A good universal system means having quality, “comprehensive services … having enough support personnel like teacher coaches [and] professional development for teachers,” said Theresa Hawley, senior vice president for policy and innovation for Illinois Action for Children. The organization worked with the city on an eight-month cost study for the program. “We helped them figure out how much it was really going to cost to do this initiative right.”

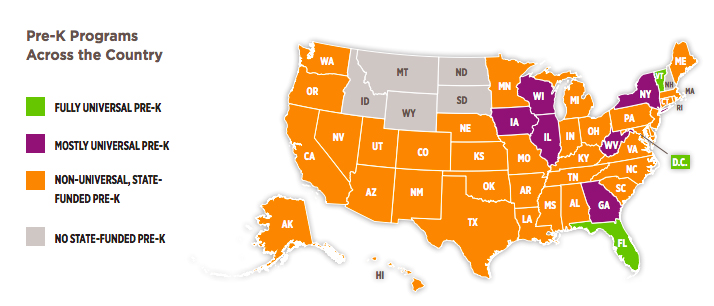

Only a handful of states and a smattering of cities, such as New York and Washington, D.C., have adopted universal programs. (There are often applications and waiting lists, however, and not every child gets a spot.)

With programs of this scale, “you need public leaders” fighting for it, said Nagle of Chicago’s Erikson Institute. So for him and other education pundits, Emanuel’s announcement last week was “shocking.”

“From where I sit in early childhood, it was clear to me that he was planning to be the mayor to see [universal pre-K] through,” he said.

Emanuel wrote in a Sept. 4 news release that he is departing for personal reasons, calling his position “the job of a lifetime, but … not a job for a lifetime.” He’ll be mayor through next May.

Chicago’s investment in early education leaves advocates hopeful that his successor will be a pre-K proponent. A handful of contenders with links to education have emerged so far in Chicago’s already crowded mayoral race, including Paul Vallas, a prior Chicago superintendent; Troy LaRaviere, president of the Chicago Principals and Administrators Association; and Neal Sáles-Griffin, who teaches at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago.

With Emanuel out of the race, the “whole conversation” shifts, Nagle said. People will now have to address the future of pre-K.

“The campaign so far [had] been everyone against Emanuel,” he said, adding that now, candidates are “going to really have to talk about the issues.”

A ‘woefully underfunded’ school system

During Emanuel’s tenure, CPS has been lauded for its fast-growing academic progress. It’s also been widely criticized for its poor financial health.

The district is “woefully underfunded for K-12,” Ralph Martire, executive director of the Chicago-based Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, told The 74. “They need [at-risk student] interventions; they need to hire more teachers.”

While the district’s budget did increase this year, the Chicago Tribune reported that CPS is facing $8.2 billion in long-term debt and a half-empty teacher pension fund. CPS has also weathered past reports of inadequate special education services and a sex abuse scandal that prompted the creation of a $3 million investigations department.

This reality makes pundits like Bruce Atchison, principal of early learning initiatives at the Education Commission of the States, wonder whether universal pre-K will fall victim to a tug-of-war for resources.

Relying on various funding streams can make programs “more vulnerable” than ones that have a dedicated, publicly backed source, he told The 74. He cited cities like Detroit, where early education is on the up-and-up after an approved ballot initiative enabled a sales tax increase to foot the bill for the city’s pre-K program.

“If voters approve something, it’s more than likely going to be more sustainable than a piecemeal approach,” he said.

For budget expert Martire, one new pre-K revenue source could prove particularly troubling: Last year’s state funding system overhaul, which prompted the state to start pumping more money annually into Illinois’s neediest districts (including CPS, where more than three-quarters of the student population are economically disadvantaged). About $60 million came to Chicago this year as a result — $20 million of which was channeled toward the universal pre-K program, according to the mayor’s office.

That $60 million “is really designed to cover” K-12 improvements, Martire said. But Illinois school districts largely control how they spend their money.

Emanuel has also been known to dedicate “a larger portion of local resources to early education than previous mayors have,” Hawley noted. The city’s budget allocated more than $15 million to early childhood this year. “So it’s up to advocates to keep the pressure on whoever is in City Hall to continue to invest.”

One form of funding that is fairly sound, Martire and Hawley agreed, is state block grants. Funding for a statewide early education block grant, for example, “is $200 million larger than it was four years ago,” Hawley said. This block grant provided the Windy City with an additional $18.5 million in funding this year.

Emanuel emphasized that there are state powerhouses in early education’s corner, such as Senate President John Cullerton, who should keep the money flowing. And, he added, state funding would likely increase if Democratic gubernatorial nominee J.B. Pritzker beats Republican incumbent Bruce Rauner in November.

Pritzker’s namesake foundation led a $16.9 million investment back in 2014 to expand Chicago’s pre-K programs. (Pritzker has a 17-point lead in the polls as of Thursday.)

‘This is the foundational year’

Emanuel sidestepped concerns that he’s abandoning universal pre-K midstream. There are many other things, he said, that he also won’t see to the end.

“I set a goal [for 2020] that to graduate high school, every child has to have a post-high school education plan,” he said as an example. “I’m not going to be here for that. But the system is being implemented to achieve that.”

The mayor and his team are approaching the rollout’s first year with a similar mindset: They call it the “foundational year.” A core element of the 2018-19 phase is building the necessary infrastructure to expand the program — including about 180 new classrooms this fall, five early learning centers, and a plan to determine which areas need the rollout the most, and when.

“Over the next eight months, I will be building out the physical capacity to handle” the increase in kids, Emanuel said. “And once that [infrastructure is] built … you can’t leave those schoolrooms empty.” (Nonetheless, other district building efforts have spurred criticism amid declining student enrollments and thousands of empty seats — especially at the high school level.)

Samantha Aigner-Treworgy, Emanuel’s chief of early learning, added that the city is also focused on providing professional development to pre-K teachers who are transitioning from teaching part-time to full-time classes. About 3,500 of the new full-day openings the city plans to create are converted over from part-time.

Whether it’s helping educators design a full-day curriculum or “supporting schools to be able to provide breaks and lunches and prep periods … we’ve really been working hard with schools [and community providers] to make sure that full day is implemented well,” she told The 74.

Meanwhile, advocates like Hawley and Nagle said they intend to spend the coming months urging future mayoral candidates to “publicly declare that they will absolutely commit now to making [universal pre-K] happen.”

“Lots of other issues are being brought” to leaders’ attention, Nagle said. “We’ve got to fight to make this the number one priority.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)