Educators Wanted Vulnerable Students To Return First for In-Person Learning, But a Racial Divide Spoiled Their Plans

When Northside Independent School District superintendent Brian Woods designed his reopening strategy, he started with the kids who needed to be there most.

He felt certain that poor, largely Black and Latino San Antonio families without access to the internet, frontline workers in need of childcare, and those struggling to keep food on the table would be desperate to get their kids back into the school buildings.

He was wrong. “The assumptions we made about who would choose to return,” Woods said, “have not largely proven correct.”

Instead, families at schools where more students are white have been eager to send their children back for in person learning. At schools where more children are Black and Latino, families have been hesitant, in part because of health concerns. These families live in multi-generational families and are less likely to have health insurance. Districts have yet to earn their trust, demonstrating that schools can keep their kids safe.

If the trend continues, Woods said, the academic consequences will be disastrous. It could take years to get back to where they were before the pandemic, let alone close the widening gaps between white, Black, and Latino students.

The divide also speaks to the disproportionate weight of the pandemic felt by Black and Latino communities. A recent report from the Centers for Disease Control revealed that 75 percent of COVID-19 deaths for people under age 21 identified as Black, Latino, or American Indian/Alaska Native. White patients are under represented in nearly every mortality measure of the disease.

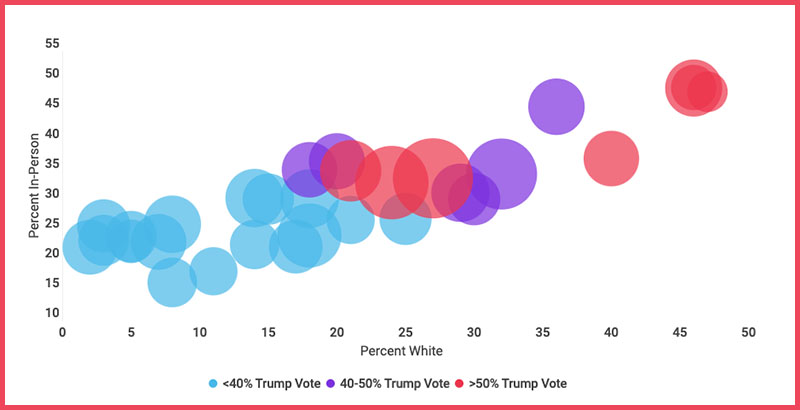

- In a random sampling of schools in Northside ISD, the largest and one of the most diverse districts in the city, the percentage of parents choosing in-person learning in August correlated to the percentage of white children enrolled.

- For instance, at Aue Elementary, where 46 percent of the 600 students enrolled in the school are white, 49 percent chose in-person learning. At Glass Elementary where 8 percent of its 450 students are white, only 16 percent opted to come back.

- Some have suggested that economics or politics may have been more influential on whether families chose in-person learning. However, the data from Northside indicated that race was more strongly associated with in-person learning preference than either the percentage of low income families at a school, or the way voters in the school’s attendance zone voted in 2016.

Nationally, surveys have shown similar trends. Black and Latino parents have their children in remote learning at much higher rates than white families. Brookings fellow Jon Valant said that doesn’t mean Black and Latino parents don’t want to send their kids back, but they may feel like they can’t do so safely.

“We do not have an education system where families of different backgrounds have equal confidence that schools will keep their kids safe,” Valant said.

Why don’t families come back?

In San Antonio and its surrounding county, 20 percent of Latinos and 15 percent of Black people 65 and under do not have health insurance. They are less likely to have jobs that offer paid time off and family sick leave, and more likely to work in industries with higher risks of COVID-19. These groups are more likely to have the underlying conditions that make the virus more deadly.

“The biggest issue is health,” said MindshiftED community organizer Maribel Gardea, “Their kids are behind and they know it, but they aren’t willing to risk sending them back.”

White families know, technically, COVID-19 is a risk to them, said Dalia Flores Contreras, interim CEO of San Antonio education nonprofit City Education Partners, but the disproportionately low impact on their communities, neighborhoods and extended families has made it manageable.

“What’s absent from the conversation is the capital you have to take those risks,” she said.

Just because a person has a middle class income now, doesn’t mean they have the same safety nets as families who have been economically stable for generations. A disruption caused by COVID-19 will have more dramatic consequences because of the kinds of jobs many Black and Latino people work and the kinds of households they live in. Black and Latino families are far more likely to live in smaller, more crowded homes, as they support their extended families. They are more likely than white families to have a grandparent in their household as well.

“The Hispanic community, we live together,” Gardea said, “Families are big.”

What will it take to bring them back?

In San Antonio ISD, where 3 percent of students are white, only 26 percent of families opted for in-person learning at the start of the school year. But as remote learning wears on, Gardea is starting to hear more families, mostly Latino, say they are desperate enough to send their kids back. They simply feel their students are not getting enough, academically. “However I do think that there is that trust issue,” she said. “They just feel that they’re just blindly trusting the school.”

She has lobbied her school to start a campus COVID-19 task force that includes parents.

At Northside’s Martin Elementary, where 2 percent of students are white, Principal JJ Perez was surprised that only 22 percent of parents said they would prefer in-person learning. Like Woods, he thought that the Title I school would see more parents needing to get kids back to school so that they could go back to work, or look for new work. What he heard instead is that they would rather keep their children away from the pandemic.

“Everyone is trying to do what’s best for their situation,” Perez said. He and his staff have been anxious to get kids back, trying to “earn the trust” of parents by showing them the cleaning and social distancing protocols the school has in place.

Families accustomed to hearing about budget crunching and the disparities between rich and poor schools, so Perez and other principals have been trying to make their mitigation strategies front and center to reassure parents that safety will not be another have and have-not issue. While few schools or districts have the time or money to widely overhaul HVAC systems or add extensive air filtration, most have tapped into emergency funding to provide personal protective equipment and sanitation supplies.

To further reassure parents, one strategy being used by most other San Antonio school districts is to contract with the nonprofit Community Labs to bring regular assurance testing to staff and students in November. Northside has not yet committed to participating in this program, telling local media they are still evaluating whether it would work for the district.

Competing goals

Black and Latino parents may feel that their concerns about safety will be drowned out by federal, state, and local political agendas, or even white parents’ desire to return to school.

“There’s sort of a long history of school systems representing some groups of families more than they represent others,” Valant said.

In Alamo Heights ISD, an affluent enclave district where 53 percent of students are white, the district has brought back more than 65 percent of students, because, Superintendent Dana Bashara told Texas Public Radio, “parents want it.”

Boerne ISD, a suburban district where 63 percent are white opened in August with around 80 percent of students attending in person.

“Personally, I feel like our district was bullied by families who wanted their kids to come back to school sooner than we should have opened,” said Boerne parent Susan Wardle. She is white, and is keeping her children home because she’s worried people aren’t taking the virus seriously.

Woods has gotten pressure from plenty of parents to bring back more kids in spite of San Antonio’s Metropolitan Health District’s guidance, which is not legally binding.

But just because families chose in-person learning in Northside did not mean they got to come back when school started bringing students in after Labor Day. Even in schools where 50 percent of students wanted to come back, the schools where more students are white, the district followed Metro Health guidelines and limited capacity to six students per classroom, prioritizing those with the most need.

Now with Northside bringing back more students, the district is up to 43 percent, teachers, counselors, support staff, and principals are making phone calls and home visits to families of students who are falling further behind each day. They are trying to convince families at largely non-white schools to send their children back in person.

Dire outcomes

If the divide between remote and in-person learning continues— along with the inequalities driving it — Valant’s predictions are grim. Distance learning as a whole has not been as effective as in person learning, he said, and to make matters worse, technology, quiet space, and homework help are not easy to come by in households struggling to get by in a deepening economic crisis. “Distance learning is harder on families living in poverty,” he said.

Woods sees no end in sight for the pandemic, no start date for a more universal beginning to “massive remediation.”

As long as the risk is there, his plan to bring back the students who need school most will likely see slow progress, he said. “An emphasis on the ‘slow’ more than the ‘progress.’”

Asher Lehrer-Small contributed to this story.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)