For the Corona Family, Normal Life Faded Away as COVID-19 Wiped Out Jobs, School and Other Daily Routines They Relied On

These days, it’s hard to tell when the Corona family’s day begins and ends.

Before COVID-19 came to San Antonio, school and work left little room for boredom or restlessness for Genevieve Corona, her husband, and their children and grandchild. With four kids in middle and high school and steady work as a courier for Uber Eats, Grubhub and Doordash, the days were packed for Corona. Two of her daughters had afterschool jobs.

With the pandemic, everything slowed. Eventually work and school stopped completely.

Precautions reduced the number of meals Corona could deliver. Restaurants had long waits as they struggled to maintain their takeout services. She was barely making enough to cover the gas. So she filed for unemployment. During COVID-19 the family’s income went from just over $5,000 per month to less than $1,500 as the restaurant and entertainment industries slowed to a halt, with employers laying off workers and slashing hours.

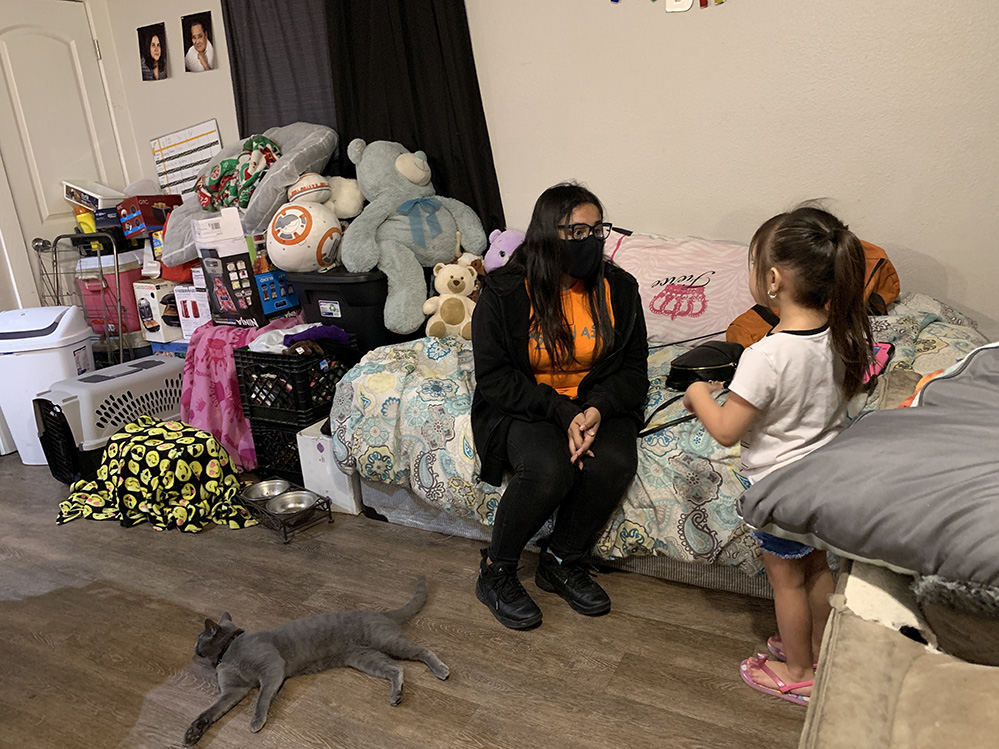

Financially, it was good that they had downsized apartments months prior to the pandemic, but it has left them — a family of seven — in extremely tight quarters at a time when there is little opportunity to leave home.

Other things vanished over time. The schedules that naturally structured their days have slowly melted away. Some of the kids struggled to stay engaged in school; one basically didn’t. With the end of online school in May, their routine all but disappeared.

Through 16-year-old Mia, the family connected to Communities in Schools, which has been helping them with basic needs.

8 a.m.

Genevieve Corona wakes up and walks the family dog. No one else is usually awake. It’s been a gradual slide into these quiet mornings.

Before March, her husband Juan and their four school-age kids — Veronica, 17; Mia, 16; Aaliyha, 14; and Jay Jay, 13 — would be up with her, earlier, walking the dog, taking turns in the bathroom, and scrambling around the two-bedroom apartment. After dropping the kids off at three different schools, Genevieve would drive for meal delivery services. Juan was the at-home parent when the kids returned from school. He has been on disability leave from his job at an auto-parts store off and on for a year, as he struggles with gout.

Once schools and businesses closed, the family still tried to keep some kind of schedule, Genevieve said, with the kids logged on to school devices during regular school hours. Without online school, the teens sleep in.

“I have a few of them who want to stay up all night and sleep all day,” she said.

Mid-morning: If she’s not already there, Genevieve’s 4-year-old granddaughter Angel arrives at some point in the morning. Angel’s father, Genevieve and Juan’s son-in-law, was diagnosed with leukemia in April. After the restaurant where she had been working shut down, Veronica stepped in to help with Angel. The chatty little girl now mixes among the family members, reading books and asking them to cue up “Baby Shark” and other preschool hits on their tablets and phones.

Having a family member in the hospital would ordinarily occupy much of Genevieve’s time, she said, but COVID-19 precautions have limited how many people can visit. Angel has seen her father only once since he went into the hospital.

10 a.m.

Mia heads to work at Urban Air Trampoline Park, where she works as a safety monitor. During the shutdown, they kept her on staff, but she came in only a couple of hours per week to help with cleaning and maintenance tasks. On June 20 the indoor sport facility reopened. Mia works about 10 hours per week. She’d like to work more, she said, but business is still slow. San Antonio’s COVID-19 cases have skyrocketed following Phase 1 reopening in May. She often gets sent home early. Still, she’s thankful for the structure.

“Going to work is my way of getting out of here and distracting myself,” she said. “If I didn’t have an escape, I would probably lose my mind.”

Around noon

Genevieve never lets her youngest kids, Aaliyha and Jay Jay, sleep past lunch, even though sometimes she can hear them watching movies well into the early morning hours. Everyone has chores to do, she said. Staying organized is imperative with seven people in the tiny apartment. Especially this summer.

“They’re like, ‘Wow, how did we dirty all these dishes? We just washed them!’” Genevieve said, laughing at her kids’ revelations.

The family downsized from a larger, more expensive apartment in October, Genevieve said, not knowing they’d all be hunkered down for months inside. Veronica and Mia sleep on twin beds in the living room, Aaliyha and Jay Jay share a room, and Genevieve and Juan have the other.

In June, the family needed a break, Genevieve said. They drove two hours to Corpus Christi and spent some time outside on the beach, where everyone had a little more room to breathe.

Afternoon

Chores and dog-walking take up some of the time, but after months of being cooped up inside, Aaliyha said, she’s feeling antsy. Of all the siblings, Aaliyha struggled the most with online school. While Mia managed to carve out her own “bubble” and make the most of online classes, Aaliyha, who has ADHD, grew more and more frustrated. Some teachers were helpful, the girls said. Others weren’t proactive, Mia said, and it felt as if students were left to figure things out alone.

“If they were to do it again next year,” she said, referencing the return to school in August, “they have to do more face-to-face calls with their students to keep them actually engaged.”

Her freshman year had already been somewhat derailed by bad decisions, Aaliyha admitted, and school closures only complicated them. Teachers and friends tried to encourage her, she said, but she just didn’t want to hear it. She was out of reach, physically, and growing out of reach emotionally more every day.

“I made lots of mistakes. I decided not to do my work, or do it last minute,” she admitted. “I decided to do my own thing, which I really regret.”

If she stays at her old school, Aaliyha said, she’ll have to repeat ninth grade. She’s considering transferring to the charter school where Veronica graduated, but she’s nervous about starting over socially.

Evening

A final dog walk after dinner closes out the day’s responsibilities, and Genevieve is usually in bed before midnight, but she can’t say the same for the kids. They’re teenagers, so this is developmentally appropriate, research shows. Still, their 2 a.m. and 3 a.m. bedtimes contribute to the sense that the days are blending together and structure is harder and harder to come by.

“Being in the house and just stuck there … it’s hard,” Aaliyha said. “It puts a lot of pressure on you, and you just can’t deal with it anymore.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)