Education Groups Demand Answers About Which Troubled Teachers Are Being Forced Back Into Classrooms — and Where

Updated Nov. 28

New York City education officials have rarely been eager to provide information about the Absent Teacher Reserve, a pool of fully paid, tenured teachers who haven’t found new positions after losing their old ones because of school closings, budget cuts, or disciplinary problems. Although some teachers are quickly hired out of the ATR, many remain for years, and almost one-third had unsatisfactory evaluations or faced disciplinary or legal charges.

Last summer, the Department of Education announced it would partly offset the cost of the ATR, which exceeded $150 million last year, by placing hundreds of the sidelined teachers in positions still vacant by late October. More than a month later, it has yet to provide records about the teachers or where they were placed.

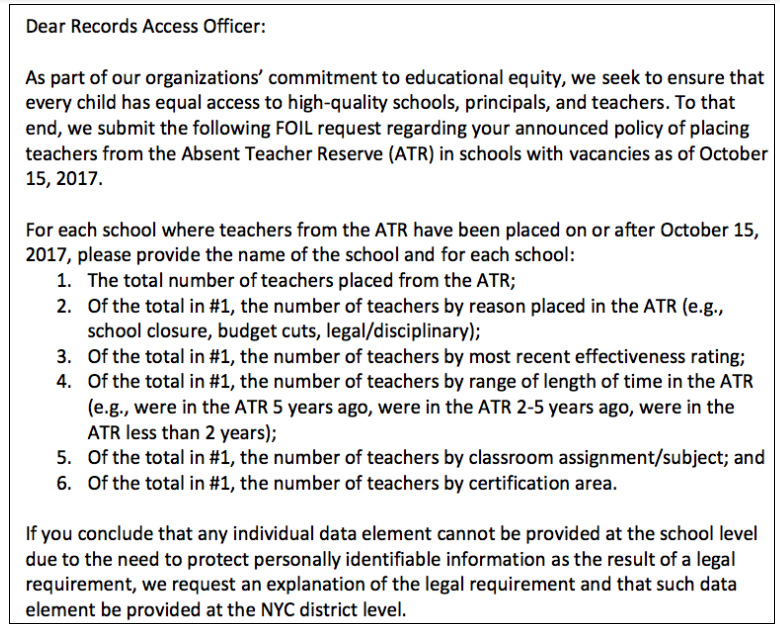

Because high-poverty districts tend to have more open positions, advocates worry that the new policy could assign “struggling and less effective teachers to disproportionately serve students of color and low-income students.” To answer the question, two education advocacy groups jointly submitted a public records request just before Thanksgiving asking the DOE for non-identifiable information about the teachers and the names of their assigned schools.

“We don’t have any transparency,” said Evan Stone, co-CEO of Educators for Excellence, which filed the request along with The Education Trust–New York under the state’s Freedom of Information Law. “There’s no line of sight into where this may be happening.”

Coincidentally, the city’s Panel for Education Policy will vote tonight (Nov. 28) on new guidelines to simplify and accelerate the department’s FOIL process. The DOE has been widely criticized for delaying or not responding to requests; its average response time was 103 days, according to a Chalkbeat analysis. The 74 found FOIL requests that had gone unanswered for more than three years.

The request asks the DOE to group ATR teachers, in each school that has them, by why they were placed in the ATR, effectiveness rating, length of time in the ATR pool, classroom assignment, and certification area.

StudentsFirstNY, a reform organization, filed a similar request in October and hasn’t received a response, according to Senior Communications Director Michael Nitzky. Other requests by the group related to the ATR, including a November 2015 filing, haven’t been filled.

The DOE declined to answer specific questions about the FOIL request or the ATR assignments.

“ATR teachers have always been in classrooms,” spokesman Will Mantell said in a statement, “and now we’re taking a strategic approach to driving down the pool — implementing hiring and severance incentives, allowing ATR teachers to cross district lines, and matching ATR teachers to vacancies to meet schools’ needs.”

A DOE official said the department wouldn’t place an ATR teacher if it had concerns about her performance or work history. The officials said the DOE planned to release “additional information” in early December.

The DOE announced in August that it planned to place about half of the ATR’s roughly 800 teachers. It also updated information about teachers in the pool: 25 percent were in the ATR five years earlier and nearly half were in it three years earlier. Almost one-third of ATR teachers faced disciplinary or legal charges. The average salary was $94,000; by contrast, a new teacher with a BA earns $54,000.

Created in 2005 to end the city schools’ decades-old seniority-based hiring practices, the ATR came with a significant cost as its numbers swelled to over 1,000. Efforts to backstop the expense — discharging those who couldn’t find a job after a fixed period of time or using buyouts — haven’t proved successful. Proponents argue that teachers who remain in the pool have poor records that make them unattractive to principals and that some don’t look for new positions. Critics, including the union, say ATR teachers are often veterans who aren’t hired because of their higher salaries.

In 2014, the advocacy and teacher training group TNTP found that 60 percent hadn’t applied for a new position using the DOE’s online hiring system in the previous year, one-third had received unsatisfactory evaluations, and 25 percent faced disciplinary charges. A 2011 city comptroller report said it couldn’t evaluate the effectiveness of the program because the DOE “presently does not formally or centrally track and maintain the data needed for such an assessment to take place.” The DOE disputed that, saying it did have such systems.

The advocates asking for ATR placement information argue that the city’s lagging response cloaks potentially worsening disparities in teacher quality.

“More than a month has passed since the city’s announced policy took effect,” said Ian Rosenblum, executive director of The Education Trust–New York. “Parents and the public deserve full and immediate transparency on how the administration’s decisions are impacting students.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)