Does Your School Have a ‘Slander’ Account?

During lockdown, hallway gossip migrated to anonymous ‘slander’ or ‘confession’ accounts. Many still operate & disrupt school culture, students say

By Asher Lehrer-Small | May 25, 2022Even at Stuyvesant High School, one of the most academically rigorous and sought-after public schools in New York City, teenage gossip is, well, teenage gossip: who’s crushing on who, who just broke up, who’s the cutest in the grade.

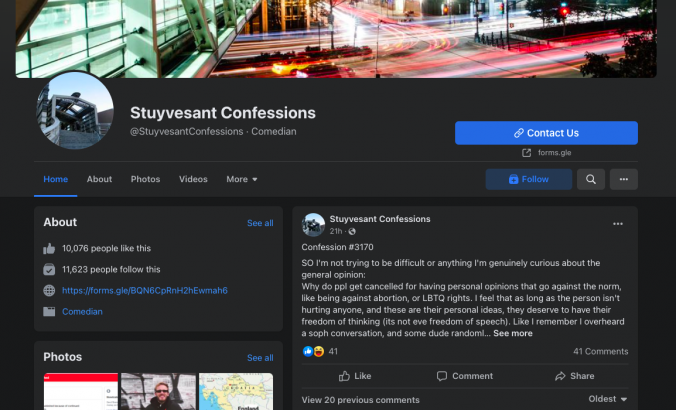

But rather than comments whispered in hallways, students frequently share those juicy nuggets through anonymous online “Stuyvesant Confessions” accounts on Facebook and Instagram that much of the student body follows religiously.

“People will be talking about it, like, ‘Did you just see the new confession?’ ” said Samantha Farrow, a junior at Stuy.

Many confessions are harmless — complimenting a classmate’s smile or admitting apprehension about prom — but others target and bully students. In Farrow’s freshman year, a post called her and two peers overweight and unattractive. Dozens of students came to their defense, she said, reassuring them the insult was completely untrue. But still, the post affected her.

“I was mad and I was upset,” Farrow remembered. “It was very degrading to my self-esteem as a 14-year old.”

Accounts like Stuy Confessions are hardly rare, students across the country report. Though the pages pre-date the pandemic, lockdown may have increased their popularity and influence as teens lost the ability to connect in person for months on end.

When schools en masse shifted online, much of young people’s socializing also migrated into virtual spaces like Discord servers, Google Hangouts and TikTok. Now two years later, even as pandemic restrictions have fallen across the country, many online communities remain, students say, and impact K-12 classrooms in ways that adults fail to understand.

“It’s really going over [educators’] heads,” Farrow told The 74. “So much stuff happens on Facebook and Instagram, the confessions accounts, and they have no idea.”

“What people post on social media kinda seeps into the classroom,” she added.

In fall 2021, when Diego Camacho’s Los Angeles high school returned to in-person learning, students began taking pictures of their peers — sometimes eating, sometimes of their shoes under the bathroom stall — and posting them online anonymously without consent, he told The 74.

He and other students “were constantly looking over our shoulders, looking around when we ate and some [of us] refused to use the bathroom out of fear [we] would end up on the pages,” said the high school senior.

It took school administration two months to shut down the account, he said. While the page was active, it “created a lot of distrust between students,” said Camacho.

At Mia Miron’s middle school in nearby Pomona, California, Instagram pages of a similar style continue to pop up despite old accounts getting banned on numerous occasions, she said. With page titles based on the phrase “Lorbeer Lookalikes,” a play on their school’s name, users send photos they took of classmates to the accounts via direct message, and the page administrator then posts the images without indicating who submitted them.

“I just followed it to make sure nobody that I know would get hurt by not knowing their photo was on there,” explained Miron.

Twice, the accounts have shared pictures of her sitting at her desk. The eighth grader doesn’t know who runs the account, she said, and did not give consent for those images to be posted.

“I wouldn’t like my photo to be on there without my permission,” she told The 74.

While Miron says she hasn’t taken the posts personally, a friend of hers was cyberbullied on the page, she said, which took a toll on the middle schooler’s mental health.

The 74 spoke with eight students in 6th through 12th grade and one college student about their experience of social media’s impact on education post-COVID. Most agreed that lockdown initially forced them to lean more heavily on online platforms to stay connected with peers and that some of those habits have since stuck around.

But the proliferation of online content and connection has also delivered some positive effects, students emphasized.

Kota Babcock, a senior at Colorado State University, said his roommate joined a pandemic Discord server they still use for weekly horror movie screenings. High schooler Ameera Eshtewi, of Portland, Oregon, hones her programming skills as a member of the online community Kode with Klossy. And Joshua Oh, a Gambrills, Maryland middle schooler, said Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter helped him and his peers quickly spread the word to wear pink in support of victims of an alleged sexual assault at a nearby high school.

Circulated within Oh’s student body, a satirical TikTok account pokes fun without crossing a line, the teen said. The “slander” page posts videos about students and teachers that he finds “funny when they are true.”

One animated clip of a cowboy coughing heavily and falling down on a train track is captioned, “What Lois thinks will happen if she doesn’t have gum for 00000.1 seconds.” Another video with the caption “Brandon trying to convince his ex to take him back” features a man flamboyantly dancing in the rain to a Lil Nas X song.

In a key difference from the pages at Miron and Camacho’s schools, none of the videos include images of actual students.

And in Pomona, as a counter to some of the online toxicity within Miron’s middle school, a student also created a school-based TikTok account featuring an “appreciation post for the girls that got put down on that other Lorbeer account.” The video pictures students’ smiling faces set to B.o.B’s Nothing on You.

Instagram and other social media can have degrading effects on youth mental health, including eating disorders and suicidal ideation, particularly for teen girls bombarded with unhealthy body image standards. Facebook (now Meta), Instagram’s parent company, has tracked the harms for years, internal documents reported by the Wall Street Journal revealed in 2021, but implemented few measures to curb the addictiveness of its app, as teen users have driven much of its popularity.

Even when students use accounts to uplift each other, ZaNia Stinson, a high school student in Charlotte, North Carolina, said that she and her peers’ dependence on social media often makes them less present IRL — in real life.

Teachers often collect phones during class, she said, and when the devices get returned afterward, “we don’t pay attention in the halls so we bump into people, like our heads are glued to [our] phones.”

During free periods at Stuyvesant, said Farrow, students will often sit next to each other in the hallway without saying a word, just scrolling. The tendency, she believes, to ignore human contact in favor of digital has worsened since COVID. From time to time, she herself pulls up Instagram during class without the teacher knowing, she admits.

Yet one online outlet has provided consistent solace for her since early in the pandemic. In June 2020, the high schooler created a Twitter stan account, or fan account, for K-pop megastars BTS, who she jokingly described as her “biggest passion in life.” She has fun chatting with other fans of the group and appreciates the low stakes because she doesn’t know any of the other users in real life, she said.

Social media is “a good outlet if you know how to use it the right way,” said Farrow. “But I don’t think a lot of people do.”

This story was brought to you via The 74’s Student Council initiative, an effort to boost youth voices in our reporting. America’s Promise Alliance helped in the recruiting of our diverse 11-member council and the idea was conceived as part of Asher Lehrer-Small’s Poynter-Koch Media and Journalism Fellowship.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter