Recapping the DNC Live Blog: Party Divisions Make Education a Risky Political Topic for Clinton

The 74 and Bellwether Education Partners are partnering to cover the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. Please bookmark or refresh this DNC live blog, which will update through Friday, or sign up for The 74 newsletter for breaking updates. (See our recap of the RNC)

The year a divided Democratic party sidelined all talk about American schools

Congratulations, Democrats, we made it through the nominating process without hearing much about what our nominee, Hillary Clinton, will do on education. Aside from a passing mention of tuition — and debt-free college for the middle class — Clinton’s historic acceptance speech last night continued the two-week convention trend of little to no discussion of education’s role in fueling our country’s future.

Conventions are mostly about rallying the base; the time for rolling out new policy positions has mostly passed.

Smart people who I admire and respect keep telling me this is fine. With the way this crazy election is going, it’s easy to understand why people aren’t anxious to have education thrown into the political scrum.

Others tell me voters don’t care about education anyway. There was a $60 million campaign to inject education into the 2008 campaign, and it mostly failed.

But I believe this thinking assumes too much linearity, from voters to candidates to governance. If we care about education, we should want our politicians to speak up. Candidates don’t just reflect voter priorities; candidates also shape how voters see the world. We know this about political parties — partisans tend to view new events through the lens of people they already trust — and we’ve seen specific examples where leadership from a politician directly influences voters.

My personal favorite anecdote about this comes from the 2000 election. That year, George W. Bush made education one of his primary campaign themes. Half of his ads mentioned education in some way (more than Democrat Al Gore’s ads did), and the most frequently-run ad throughout the 2000 cycle was a Bush ad calling for higher standards for our schools.

Agree with Bush’s ideas or not, it had an effect. In 2000, voters selected education as one of the top issues facing the country, and Bush used the education issue to signal his “compassionate conservatism” — earning female and minority voters in numbers that Republicans typically aren’t able to. Besides helping get him elected, he now had a mandate for policy, and Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act was a direct consequence of the way he ran his campaign.

Again, you don’t have to like Bush’s particular policy prescriptions to appreciate the chain of events here. The point is that education can matter if politicians decide it does. And if politicians campaign on an issue, they can then govern behind a mandate.

It’s not clear that Donald Trump has spent much time thinking about our nation’s public schools, so it’s no surprise he hasn’t spent much time talking about it.

But Hillary Clinton is another story. She’s devoted large portions of her life to fighting for kids who depend on our public schools. We heard Bill recount this history on Wednesday night. The reason Clinton hasn’t spoken up about education this year isn’t because she doesn’t care or doesn’t have ideas; it’s because the politics within the Democratic Party don’t encourage it. As Kate Pennington and I pointed out last month, Clinton relied on a coalition of union workers and black and Hispanic families to win the nomination. Those groups are opposed to change on a range of education issues, including charter schools and the role of testing and school reform efforts.

Why should Clinton risk Democratic Party unity to speak out on education?

For starters, it would be the right thing to do. No one can reasonably assert our public schools are as good as they could or should be, especially for students with disabilities and low-income, black, and Hispanic students who depend on them the most.

But more importantly, Clinton should have laid out her education policies so she’ll have legitimacy to act on education once she becomes president. In particular, Clinton declined to speak out during last year’s debate over the Every Student Succeeds Act. Now that the law’s signed, there are significant implementation issues left to be addressed. The law leans on vague phrases like “significant progress,” “meaningful differentiation,” and “consistently underperforming,” and the federal government is currently soliciting feedback on what exactly these phrases should mean.

What do these phrases mean to Clinton, and how aggressive would she be in defining them? Does she support equalizing funding in low-income schools, even if it means some districts would have to change their funding structures? What kind of leader would she put in place to oversee regulations and implementation of the new law?

We don’t know the answer to these questions, but they matter. Without signaling what she prefers, Clinton won’t have as much leeway once she’s elected. Silence, too, has consequences.

We may not have heard much substantive conversation about education from the podiums in Cleveland and Philadelphia, but that shouldn’t discourage us from pushing the dialogue forward. If you care about education or the direction of education policy in this country, you should want your politicians to speak up about it, too.

— Chad Aldeman (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

I spent a good portion of Thursday evening, while watching Hillary Clinton’s history-making acceptance speech from inside the Wells Fargo Arena, thinking about one of my elementary school classmates back in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, one of a string of middle-class suburbs that cropped up outside the state capital of Harrisburg after World War II.

Amy, who had Down Syndrome, was in my class starting in third grade. Although I’m sure she was pulled out for the core academic classes, she was definitely around for recess and art and music and the field trips (including our fourth-grade trip to Philadelphia in conjunction with that year’s social studies lesson on Pennsylvania history.) She was in my Brownie troop, too, raising her pinky and putting on a fake British accent with the rest of the girls as we practiced our best manners at a Mother’s Day tea.

I’d heard the story of Clinton’s work with the Children’s Defense Fund probably a dozen times before Thursday. A slight running joke in my newsroom during the DNC was, “Did you know that Hillary worked for the Children’s Defense Fund?”

Of course you did if you care about education and have paid even half-attention to the election. You know the story too: puzzled by the discrepancy between the number of school-age kids on the census and the number enrolled in local schools, Children’s Defense Fund researchers, including Clinton, set out to find those kids and figure out why they weren’t in school.

The missing, for the most part, were children kept out of school because they had some sort of disability. Clinton remembered one particularly in her speech Thursday night, a girl in a wheelchair in the working class town of New Bedford, Massachusetts, who sat on her parents back porch, longing to go to school.

That research, Clinton said Thursday, became the impetus for the law now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, a major civil rights education law that came into being in 1975.

“It’s a big idea, isn’t it? Every kid with a disability has a right to go to school,” Clinton said Thursday. “But how do you make an idea like that real? You do it step by step, year by year, sometimes even door by door.”

I’m ashamed to say that it wasn’t until I was sitting in that crowded convention hall, watching a barrier be lifted, that I truly realized just how big of a deal it was that — thanks to that year-by-year progress — Amy’s presence in those classes and at that tea wasn’t novel at all. Nor was it out of the ordinary for Abigail, another intellectually disabled classmate, to beat me at bowling in high school gym class. Or to see Dan, maybe the smartest kid in our class at Cedar Cliff High School, passing through the hallway, also in a wheelchair, during his too-brief period of remission as he battled a brain tumor.

It’s been easy, as a reporter trying to cover education in this election, to get bogged down in bemoaning the lack of substantive debate on education or giving too much weight to a throwaway applause line in a speech. Something to tweet about finally.

We can talk till we’re winded about why Obama didn’t discuss his education legacy and what that means about the civil rights/labor union split in the Democratic Party on education, or about what the GOP’s backing away from the Common Core — despite its support from the usually Republican-aligned business community — means about the future of that party.

The Democrats’ convention was also notable for the prominent speaking roles given to several disabled Americans. Children and adults with disabilities were for too long marginalized and segregated in a way that didn’t give them a voice in their own lives. Clinton remembered them in her speech Thursday night and so did I.

— Carolyn Phenicie (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Gov. Cuomo demands equal school funding at DNC — but his home state tilts in the wrong direction

Sen. Bernie Sanders focused much of his 2016 primary bid on income inequality and the million-ahs and billion-ahs who, in his eyes, immorally and illegally profit at the hands of working men and women.

Early Thursday evening at the DNC, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo shifted that focus towards inequal support of America’s youngest citizens.

There are two education systems in the United States – not public and private, but rich and poor – Cuomo told the already-over-capacity arena in Philadelphia.

If you go to a school on the “rich side of town,” leaders will show you how all the first graders have laptops, Cuomo said. On the poor side of town, though, “the most sophisticated piece of equipment is the metal detector.”

Cuomo’s emphasis on school funding marks a sharp departure from comments he made about education dollars in 2014: “We spend more than any other state in the country. It ain’t about the money. It’s about how you spend it — and the results.” The advocacy group Alliance for Quality Education — a New York-based nonprofit that backs increasing school funding — has also criticized Cuomo’s record on this issue. A 2015 report from the group says that under his watch, funding disparities between rich and poor districts has increased and now amounts to several thousand dollars less per pupil. A recent report from the Education Law Center rated New York as “flat” for its funding fairness (the middle of three categories).

Democratic voters are sure to hear more about the issue in the coming months; school funding within districts has become one of the political flashpoints in implementing the Every Student Succeeds Act, the new federal K-12 education law.

That ongoing funding inequity, Cuomo concluded, “is not educating every child equally.”

— Carolyn Phenicie (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

From mass incarceration to education: Hillary Clinton’s second chance

In 1996, Hillary Clinton, in support of her husband’s sweeping crime bill, gave an interview in which she invoked the “superpredator,” a criminal so corrupted that they were irredeemable. That narrative stoked the fear that has driven two decades of prison and jail expansion, militarized local police, and zero tolerance school discipline policies. But times have changed.

In just the last few years, we’ve watched the tide turn in our national discourse on incarceration, and it’s clear that the speakers at the convention have joined the call by Education Secretary John King and others to shift resources away from the criminal justice system and into our schools. It’s not just our federal leaders — in a crisis of conscience, states, school districts, and public charter schools are rethinking their approaches to student behavior. They’re spurred by a realization that they have been complicit in a broken system.

Dr. Maya Angelou once reflected, “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.” During the primary campaign, there were loud voices insisting that Hillary’s 1996 comments were fair game for criticism. And they were. But if we as a society take the principles of growth and redemption seriously, then we need to take a close look at what’s different about this campaign and how Clinton has changed in the last 20 years. If you believe in second chances, then that stuff matters.

Hillary has spoken explicitly about racial justice, mass incarceration, and the need to invest in supportive services in communities. Kate Burdick, a long-time education advocate, Eric Holder, and the students of Eagle Academy, joined the lineup of speakers to talk about Hillary’s focus on education and justice reform. On Monday night, Bernie Sanders credited Hillary Clinton with understanding that we need to make sure that young people “are in good schools and in good jobs, not rotting in jail cells.”

And while Hillary shouldn’t be accountable for her husband’s policies, she is responsible for her own words — words that she now publicly regrets.

If she now follows up that regret with real action on education like her platform suggests, it could be a demonstration of the self-aware leader who does better once they know better — and an example for us all.

— Hailly T.N. Korman (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

In an interview yesterday with Education Week, National Education Association president Lily Eskelsen Garcia floated a new epitaph for education reformers: “their balloon is pffft!” And with the notable exception of Michael Bloomberg, those sentiments have been on display at the DNC podium in Philadelphia this week.

If Secretary Clinton succeeds President Obama, it appears education reformers may lose influence in K-12 while teacher unions take the driver’s seat on policy.

But I’d argue the long-term trends are actually in education reform’s favor:

- School choice is here to stay because families want a say in where their children go to school. We are now arguing about the best ways to offer families choice, not whether empowering families is a good idea.

- This may be counterintuitive, but I think a Clinton presidency will increase the types of innovations we see from the education reform community. I expect new forays into areas like career and technical education, social-emotional learning, and community engagement — areas that have not garnered as much attention from reformers in the past. We’ll also see a third wave of innovations from high-performing charter schools [Note: I fund high-performing, charter public schools in my day job]. The result: a bigger political tent and a more innovative platform.

- I believe Latinos and African-Americans will exert more pressure on traditional education systems to improve. Communities of color are growing in size and importance. There is pressure to diversify public education leadership. And the leadership baton is being handed from one generation to the next. My father had Jesse Jackson and Henry Cisneros. My generation has Brittany Packnett and HUD Secretary Julian Castro. The Democratic Party already has a wary relationship with civil rights groups when it comes to education. Some day we’ll see a Mothers of the Movement-like speech at the Democratic convention about our schools. I suspect people of color will realign politically around public education in powerful, albeit unpredictable, ways.

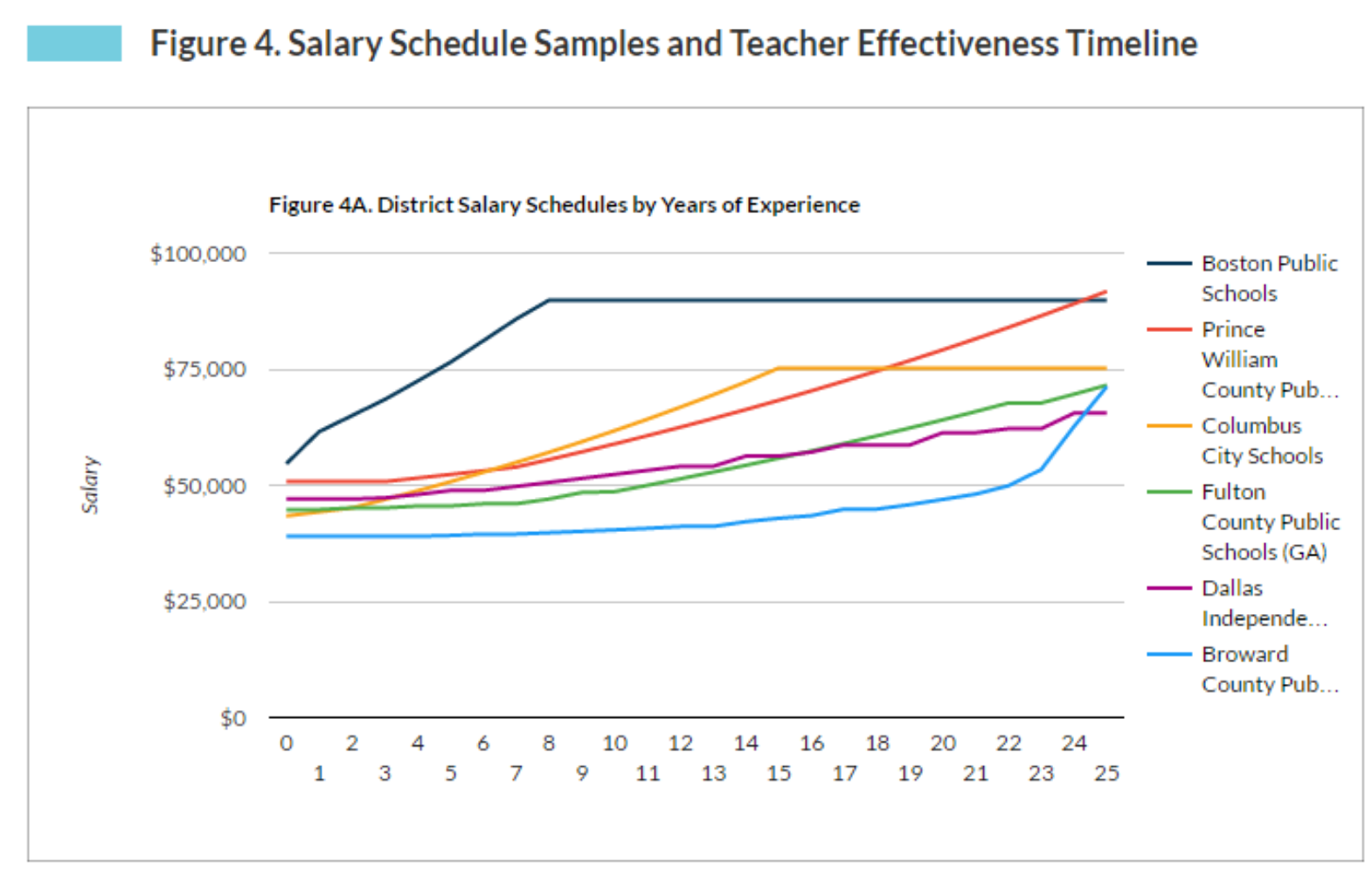

- The long-term financial outlook for many traditional school districts is rough. Unfunded pension and benefit liabilities means dollars are being taken out of classrooms and teacher paychecks are shrinking because school districts have no other way to pay their retirees. In Pennsylvania for example, schools must pay 30 cents to the retirement system for every dollar of payroll. This also means any new school funding covers pension shortfalls and never finds its way to teachers and classrooms. Voters will wonder if there is a better way and unions will spend massive political capital on taxpayer bailouts.

A transition from Obama to Clinton is a pendulum swing, not a permanent realignment. Reformers may find some of their White House invitations get lost in the mail and that the political temperature goes up for a few years, but the opportunities to create better schools for children may be greater than ever.

— Alex Hernandez (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Last month, Hillary Clinton laid out an initiative on technology and innovation at Galvanize, a nationally-recognized technology incubator in Denver. The proposals are wide-ranging, from talent to cyber security — and, surprisingly, may include what’s perhaps her most detailed K-12 plan around STEM education.

The slate of proposals is impressive and it includes ideas that will keep many sectors competitive domestically and globally. But for some reason, many of the strategies that Clinton proposes for transforming manufacturing, transportation, energy, and healthcare don’t explicitly apply to the education sector.

Instead, Clinton’s platform positions the education sector as a means to an end, preparing a knowledgeable workforce that will advance other sectors — but the sector is not recognized as one that would benefit from serious innovation efforts that others enjoy.

This perception is indicative of how most people, even reformers, perceive the education sector. Perhaps it’s because the U.S. education system is so localized, because people and lessons from the private sector are suspect, or because there isn’t a lot of exposure to successful and responsible innovation efforts. Whatever the reason, this perception is keeping the education sector from evolving and improving.

Our country’s worst performing schools and chronically underperforming districts do their best to make incremental improvements, because the K-12 education sector in America lacks the kind of robust public and private infrastructure to take on serious innovation.

For all of the rhetoric about staying competitive with Singapore and Finland, scant attention is given to the role that innovation can play in making that happen. Research, development, and innovation-friendly policies are critical in keeping other sectors competitive. Why shouldn’t that be true for education?

While the context may differ, the concepts that drive innovation in other sectors can and should apply to the education sector. Clinton’s campaign could fill its vacuous K-12 education platform with ideas it already has in its innovation and technology platform.

Here are a few strategies that Clinton should apply to education:

Increase Access to Capital for Growth-Oriented Small Businesses and Start-Ups, with a Focus on Minority, Women, and Young Entrepreneurs: There’s a lot in Clinton’s technology proposal — incubator creation, student loan deferral for entrepreneurs, and global recruiting for STEM professionals and entrepreneurs — all of which have applications in education. Tom Vander Ark of Getting Smart and David Fu of 4.0 Schools make the case that intermediaries like incubators, accelerators, and funders are key to making an education ecosystem thriving and dynamic. My own project underway at Bellwether to measure the level of innovation in education ecosystems supports this notion. Clinton’s announcement at Galvnize signals their importance. When combined with strategies to recruit entrepreneurs, startup assistance for organizations that launch new school models, programs, and products can get a city or state’s innovation flywheel spinning.

Invest in Science and Technology R&D and Make Tech Transfer Easier: According to the Clinton campaign’s brief, “Hillary believes the benefits of government investment in research and development (R&D) are profound and irrefutable.” Yet her commitment to R&D doesn’t extend to the education sector. Right now, the U.S. invests only around three percent of its federal education budget on R&D, and the trends don’t look like that’ll change any time soon. The R&D obligations for the federal Department of Education have been decreasing steadily since 2006. The DOE’s Office of Innovation and Improvement’s 2017 budget is down 17 percent from 2016 compared to a department-wide reduction of just 0.32 percent. Closing the opportunity gap has proven more difficult than putting a man on the moon, so perhaps our investments in innovation should match the enormity of the challenges educators face.

Ensure Benefits are Flexible, Portable, and Comprehensive as Work Changes: In a recent blog post, my colleague Max Marchitello points out that most teacher pension plans restrict the mobility and savings potential of teachers, and Clinton’s proposal to create flexible, portable, and comprehensive benefits to workers should apply to the second largest workforce in America: “The teacher workforce — like nearly every labor force in America — has evolved considerably. No longer are teachers educators for life, nor do they live in a single state decade after decade. Teachers are mobile. They enter and exit the workforce at different points in their lives. Nevertheless, teacher pension systems have persisted for more than a century with more or less the same structure. By increasing flexibility and portability for teacher retirement benefits, we can ensure that teachers don’t have to choose between working with kids and earning a healthy start on retirement saving.”

Reduce Barriers to Entry and Promote Healthy Competition: One of the more interesting, powerful, and likely controversial ideas for increasing innovation in the education sector is to make sure entrepreneurs don’t have to overcome bureaucratic obstacles to implement new ideas. The brief states that “Hillary will challenge state and local governments to identify, review, and reform legal and regulatory obligations that protect legacy incumbents against new innovators. Examples include state regulations governing automotive dealers that stifle innovation and restrict market access, or local rules governing utility-pole access that restrain additional fiber and small cell broadband deployment.”

A classic example of this happening in the education sector is when school districts (legacy incumbents) make access to facilities for charter schools difficult or impossible to prevent their openings or expansions. So many policies and special interests exist specifically to protect legacy incumbents that pursuing this with seriousness would shake up the K-12 education space considerably.

Open up More Government Data for Public Uses: Data is essential for good decision-making, but accessing and analyzing government data in the education sector is often a dreadful experience, a topic about which I’ve recently written. Opening up more government data for public use is important, but the federal government can also use its heft to collect and analyze complicated quantitative data. A recent report on K-12 labor productivity by the Bureau of Labor Statistics signals that this may occur more in the future. Clinton could take a more aggressive stance and require states to conform to specific data reporting standards and timelines.

When ESSA is shifting power to states, quarterbacking innovation efforts would be a way for the federal government to extend their influence beyond policing states accountability systems. And, the U.S. Department of Education already has an office to do it.

The DOE’s Office of Innovation and Improvement (OII) is a natural home for these activities, but a mindset shift would be required there to make them happen. It would have to focus more on creating and executing on policies that create the conditions for others to implement new ideas instead of funding programs with very specific aims. Their Investing in Innovation (I3) grant competition, Race to the Top District, and credit enhancement service for charter school facilities are example of steps in the right direction.

Realizing the vision to make the U.S. education system equitable and excellent will require new ideas and new ideas happen through innovation activities. Other industries have made innovation a central strategy to stay competitive and there are many lessons that can inform the education sector. If Clinton should become president and wants to modernize the federal role in K-12 education, she’d benefit from looking at her own proposals for other sectors for a path forward.

— Jason Weeby (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

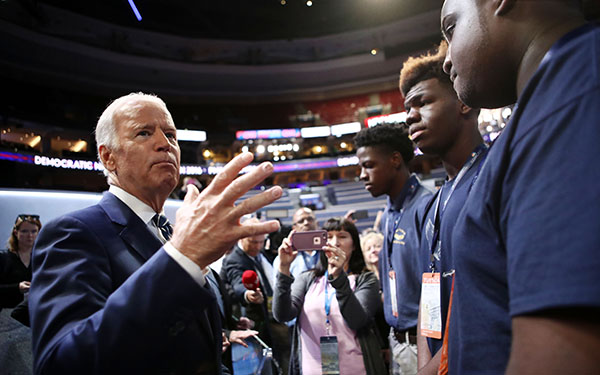

“Hey guys … Where are you from?”

It was Joe Biden, walking over to shake hands and talk with almost 40 students who’d traveled from the all-boys Eagle Academy for Young Men in New York City to represent their school on the national stage.

Chatting with the vice president was one of the heart-stopping highlights of a whirlwind day in Philadelphia, said Mayfield, a rising sophomore from the Morris Heights section of the Bronx.

“If you put in the effort and you live by (the Eagle Academy motto) CLEAR — confidence, leadership, effort, academic excellence and resilience — the opportunities are endless,” the teen said in a phone interview Wednesday.

“Look at me,” he added, “when I was on stage at the Democratic convention with my Eagle Brothers, I just can’t believe … how many boys who look like me can say they achieved that?”

The students chanted “Invictus” for Biden — one of his favorite poems, the vice president told them, which he’d taught to his son Beau, who died last year — a preview of the performance they’d give before the full convention hall later that evening.

“Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.”

The title of the poem by the English writer William Ernest Henley comes from the Latin “undefeated” or “unconquerable.” Nelson Mandela drew strength from it while in prison, Eagle Academy President and CEO David Banks said, and Eagle Academy students recite it daily as a rousing reaffirmation of their own courage and dignity as they confront challenges.

When the first Eagle Academy opened in the Bronx in 2004, with Banks as its principal, it was the first-of-its-kind all-boys public school in New York, Banks said.

That school year, 2004-05, only 30 percent of New York City high school students graduated with a Regents diploma. Even more staggeringly, 75 percent of New York state’s entire prison population at the time came from just seven New York City neighborhoods, according to Banks.

“If you were one of the young men growing up in these areas, the odds were stacked against you,” he told the convention.

He explained to the convention audience how Hillary Clinton’s support was crucial in the years leading up to the school’s establishment. In 2001, then-Sen. Clinton co-sponsored a provision of the No Child Left Behind Act that provided federal funds to single-sex public schools, spurring local school districts across the country to experiment with gender segregation.

“She was our earliest champion,” Banks said. “One leader who understood that addressing the crisis facing young men of color in our country required innovative measures.”

The school was established through a collaboration with the nonprofit One Hundred Black Men, and Clinton helped encourage then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg and then-Schools Chancellor Joel Klein to support the public-private partnership, according to her website.

Like all public schools, Eagle Academy receives taxpayer funding; it also has an active fundraising operation, the Eagle Academy Foundation, which helps support an extended school day and Saturday programming, Banks said.

Today it serves about 3,000 young men, mostly of color, at six locations — one in each New York City borough and one in Newark, New Jersey. Since its first graduation in 2008, which Clinton attended, the academies have graduated about 1,000 students. Roughly 83 percent of students graduate and 98 percent are accepted to college, Banks said.

His students’ televised appearance at the convention, Banks said, served as an important reminder to a populace that is far too often awash in negative images of young African American and Latino men.

“Today we have young men who are confident, future leaders who are resilient. Just look at them, America,” Banks boomed, drawing applause. “They are brilliant and full of promise.”

— Mareesa Nicosia (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

The message of Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton’s ad is simple.

Young big-eyed children watch a television set with fixed gazes as her Republican rival, Donald Trump, says offensive things about Mexican immigrants, women and a disabled reporter.

Then these words flash across the screen: “Our children are watching. What example will we set for them?”

It’s not the first time that this idea — that voters should pick a president who is a good role model for children — has surfaced in this election. In a much-heralded speech before the Democratic National Convention on Monday night, First Lady Michelle Obama echoed similar sentiments when she said that she and President Barack Obama take seriously their job as role models for kids.

“We know that our words and actions matter not just to our girls, but to children across this country —kids who tell us, ‘I saw you on TV, I wrote a report on you for school,’” she said.

Donald Trump’s daughter, Ivanka Trump, seemed to rebut the suggestion that her father would be a poor role model for America’s youth by instructing voters during the Republican National Convention to “judge his values by those he’s instilled in his children.”

But are politicians really role models for kids? At a time when it’s easy to peruse the latest vacation photos of your favorite pop artist on Instagram or become a celebrity in your own right through sheer volume of YouTube views, are kids really looking to the occupant of the Oval Office for validation, motivation and moral grounding?

A few research studies suggest the answer is yes—mostly for kids who see themselves reflected back in the president’s image. Since at least 1995, social scientists have argued that members of negatively stereotyped groups (think women in a math or engineering class and African Americans on a host of cognitive tasks) are at risk of conforming to that stereotype simply because they are aware of it.

Seeing someone of your social group achieve an ultimate marker of success, such as being elected to office, can interrupt that negative default. In fact, a 2006 study in the Journal of Politics found that when women politicians get more national news coverage, young girls are more likely to say they intend to be politically active themselves.

Likewise in 2009, a team of researchers from three universities released a study that argued that there was an “Obama Effect” on the academic performance of black Americans because of his accomplishments. The researchers gave a 20-question test to blacks and whites four times during 2008, two times when his candidacy was particularly soaring (the day after the Democratic National Convention and the day after the election) and two more ordinary days.

When Obama’s “stereotype-defying accomplishments” were getting national exposure, black’s performance on the exam was improved.

“In some testing situations, they experience a ‘stereotype threat’ and perform poorly,” Sei Jin Ko, one of the study’s authors told The Daily Northwestern. “It’s not that they don’t have the ability to do well, but they feel that if they don’t do well, they will perpetuate the negative stereotype and in turn, this worry makes them do worse.”

The extent that a president’s election can offset the effects of the stereotype threat may have something to do with the way adolescents interpret their success. A 2011 study found that when women were reminded of the stereotype that their gender struggled with math, they were less successful on a cognitive test.

But when they read a story about Hillary Clinton’s life and indicated beforehand that they thought her accomplishments were deserved, they scored better. For women who attributed Hillary Clinton’s rise to luck or connections, reading about her life offered no protection against the stereotype threat.

On Tuesday after officially securing the Democratic nomination, Clinton wasted no time portraying her candidacy as a milestone achievement, saying in a video, “We just put the biggest crack in that glass ceiling yet.”

— Naomi Nix (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Flashback: The first time Hillary Clinton was tested as a public school supporter

The year was 1993.

President Bill Clinton had just beat Republican incumbent George H. Bush and the first family was facing an early political test: Where would they send Chelsea Clinton, their 12-year-old daughter and only child, to school?

On the campaign trail, Bill Clinton had portrayed himself as an ardent supporter of public education. He even sent his daughter to Horace Mann Magnet Middle School, a public school in Little Rock, Arkansas where 59 percent of the students were black and 41 percent white. (Today, out of some 760 students, 58 percent are black, 26.5 percent are white, 11.7 are Hispanic and 1.7 percent are Asian.)

Local Washington, D.C. officials invited the first family to choose a city school as a show of good faith. But days before Clinton’s inauguration, the family announced that Chelsea would be attending one of the region’s most exclusive private institutions: Sidwell Friends School.

“It’s an academically challenging school,” Clinton spokesman George Stephanopoulos said at the time. “And it’s a school that Chelsea and her parents feel that she’ll be challenged and productive and happy in.”

Chelsea Clinton would join an elite group of students that included the children of Washington Post publisher Donald E. Graham, former New Mexico Sen. Jeff Bingaman, and New Jersey Sen. Bill Bradley.

Criticism of the Clintons’ school choice was swift and broad.

Michael Casserly, the executive director of the Council of the Great City Schools, a Washington, D.C.-based coalition of city public school systems, called the Clintons’ decision an “unfortunate vote of no confidence in urban education.”

Enrolling Chelsea in a public school “would have been an excellent opportunity to spur greater parental involvement in urban public schools and to work hand in glove with the public schools from both a political and personal standpoint” he said.

Former D.C. school board member Sandra Butler-Truesdale told The Washington Post that if Clinton had picked a public school, “it would have boosted the morale of educators in this city. It would have made such a big difference in the way education is delivered.”

Rebuke also came from national political figures. Then-Secretary of Education and now U.S. Sen. Lamar Alexander told CBS Morning News that the first family made a wise choice for their daughter — Alexander’s son had just graduated from Sidwell Friends — but were being hypocritical because Clinton opposed Republican calls for school vouchers that would have helped needy parents make a similar choice.

Bill Clinton had argued that vouchers would drain money from public schools; Hillary Clinton also opposes the policy.

With tuition at Sidwell Friends back then more than $10,000 a year, some 27 percent of its 1,030 students were minorities when Chelsea Clinton was admitted. Sidwell Friends remains popular among Washington’s powerful families, most famously President Barack Obama’s daughters, Malia and Sasha. The school’s tuition has risen to $39,360, with only 23 percent of students receiving any kind of financial aid, according to the its website. The school was founded in 1883 by Thomas W. Sidwell to uphold the Quaker principles of peace and justice.

Even former president Jimmy Carter, who was the first president in 71 years to send a child to a D.C. public school while in office, said he was “disappointed.” His daughter, Amy, attended public schools throughout her four years in Washington, including Stevens Elementary School and Hardy Middle School, a predominantly black school. Amy Carter went onto Brown University but was asked to leave her sophomore year. She finished at Memphis College of Art and then got her master’s at Tulane University.

Chelsea went onto Stanford University (and Columbia and Oxford); Malia will enter Harvard in fall 2017 after taking a gap year. The Bush daughters, Jenna and Barbara, had both graduated from Austin High School in 2000, the spring before their father took office. Jenna went onto the University of Texas and Barbara became the fourth-generation Bush to attend Yale.

Amid the Sidwell storm, the Clinton family defended the choice saying, “we believe this decision is best for our daughter at this time in her life based on our changing circumstances.” Hillary Clinton added later that a private school would allow the family to better maintain Chelsea’s privacy—a sentiment she reiterated in her 2003 memoir, “Living History.”

“Our decision about where to send Chelsea to school had inspired passionate debate inside and outside the Beltway, largely because of its symbolic significance. I understood the disappointment felt by advocates of public education when we chose Sidwell Friends, a private Quaker school, particularly when Chelsea attended public schools in Arkansas. But the decision for Bill and me rested on one simple fact: private schools were private property, hence off limits to news media. Public schools were not. The last thing we wanted was television cameras and news reporters following our daughter throughout the school day as they had when President Carter’s daughter, Amy, attended public school.”

The press during Bill Clinton’s administration would, in fact, develop a general no-coverage rule when it came to the First Family’s children.

On Chelsea’s graduation day from Sidwell, though the Clintons did not seem to mind the public attention. During a two-hour outdoor ceremony, President Clinton gave a short, bittersweet talk in which he instructed the high school graduates to “indulge your folks” if they seem sad as they remember all the milestones their children have reached. Obama actually declined an invitation to speak at Malia’s graduation, saying he would be wearing dark glasses and crying.

Hillary Clinton also waxed nostalgic in her syndicated newspaper column that week: “Like parents across the country,” she wrote. “We find ourselves fighting back tears as we contemplate what our days will be like when our daughter leaves the nest to embark on a new stage of life.”

Tonight, it will be Hillary embarking on a new stage of life — and history — when Chelsea introduces her mother, who will make her acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention.

— Naomi Nix (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Forget Joe Biden or Tim Kaine or Lenny Kravitz – one of the breakout stars last night at the Democratic convention was a spirited septuagenarian school board member from Ohio.

The crowd inside the Wells Fargo Center was confused at first, when the announcer said the speaker introducing President Obama would be someone named Sharon Belkofer. She knew it, too, saying she had a sense the audience was asking itself why this “little old lady,” a mother, grandmother and great-grandmother, was on stage.

Belkofer, it turns out, has quite the story. One of her sons was killed in Afghanistan, and she ended up meeting the president twice. Inspired by their second meeting, she says she vowed to make a difference herself.

“I knew my community’s schools needed more resources, so at age 73, I took a leap of faith and ran for my local school board,” she told the immediately-delighted crowd, which erupted into one of the louder cheers of the evening.

When her back acted up as she was campaigning, walking the street and knocking on doors, Belkofer says she kept on, inspired by her son and by President Obama. And, she quipped, “they say walking is good for your back.”

She won the election – big, she said – and earned a seat on the Rossford Exempted Village Schools in northwestern Ohio. The President wrote to congratulate her.

And that’s how Sharon Belkofer landed a prime-time slot at the Democratic National Convention.

— Carolyn Phenicie (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Courage, conviction, and chutzpah. It was classic Mike Bloomberg at last night’s DNC convention, as the former mayor of New York City (and my former boss) spoke to a primetime audience about why He’s With Her.

While passionately making the case for Hillary Clinton, slinging zinger after zinger at Trump, he also admitted his differences with the Democratic nominee and both political parties. “I don’t believe either party has a monopoly on good ideas or strong leadership,” he said, going on to chide Democrats for standing in the way of education reform, among other policies. That elicited a few boos, but not as many as I would have expected given how the teacher’s unions have been touting their influence throughout the convention.

Why raise the issue of education? Because Bloomberg has witnessed what’s actually possible. As mayor of the largest school system in the country, he partnered with visionary schools chancellor Joel I. Klein to stand up to teacher unions and push politics aside to do everything in their power to ensure all 1.1 million NYC students had access to a quality public education. I know, because I saw it firsthand as part of their crusade to put children first.

Bloomberg and Klein are responsible for implementing far-reaching changes in the system as part of the most ambitious urban school district reform in recent history. But Bloomberg didn’t say what he said to the Democrats because of what he and Joel Klein did. He said it because of what their work did for students.

My colleague Matt Barnum surveyed the research on these reforms just yesterday: “Teacher quality seemed to improve as tenure decisions became stricter; schools with an F letter grade got better; small schools boosted high school graduation and college enrollment; charter schools improved test scores; school closures led more students to graduate; retained students did better on tests; new teachers, particularly those in high-poverty schools, had better qualifications; schools in the city were funded more equitably.”

And the list goes on.

Bloomberg and Klein led the most ambitious overhaul of any city school system so that it worked on behalf of all students, and not on behalf of just some. That took standing up to special interests who benefitted from maintaining the status quo. It took standing up to the Democratic machine.

There’s a lot of speculation as to whether Hillary Clinton will pivot away from President Obama’s forward-thinking education policies, which embraced innovation and created pathways enabling students to choose a high-quality school. In deciding which way to go, Hillary should take take a cue from one of her most important, courageous, and sensible surrogates, Mike Bloomberg.

— Romy Drucker (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Disclosure: The 74 is partially funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, which was founded by Michael Bloomberg.

When Erica Smegielski heard there was a shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, she grabbed her keys and rushed to the building where her mother worked as the principal. At first, she couldn’t believe her mother had been gunned down, murdered, along with 20 children and five other staff members.

Like too many other American victims of gun violence, she couldn’t wake up from her worst nightmare.

“We don’t need another Charleston, or San Bernardino, or Dallas, or countless other acts of everyday gun violence that don’t make the headlines,” Smegielski said in her speech Wednesday night at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. “We don’t need our teachers and our principals going to work in fear. What we need is another mother who is willing to do what’s right, whose bravery can live up in equal measure to my mom’s.”

Through the lens of school violence, Smegielski used the DNC stage to highlight American gun violence as Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton promotes expanded criminal background checks and the renewal of a ban on assault rifles on the campaign trail. For decades, America’s relationship with guns and mass shootings has been framed — both by Democrats and Republicans — around violence against students and educators.

In fact, Wednesday night’s focus on criminal justice reform and gun violence occurred just days before the 50th anniversary of America’s first mass shooting on a college campus, in which Austin police officers found themselves outgunned by a University of Texas engineering student who killed 16 people from the 27th floor of a campus tower. On Aug. 1, the anniversary of the killing, a controversial state law will go into effect that loosens handgun restrictions on college campuses.

On Wednesday, Smegielski shared the stage with victims of the Pulse nightclub attack in Orlando, Fla., where 49 people were killed on June 12, and victims of the Emanuel Church shooting in Charleston, S.C., where nine people were murdered in June 2015.

The debates, and policies intended to crack down on school violence, intensified following the Columbine High School massacre in 1999 in Colorado, and again after the Sandy Hook violence in Newtown, Conn. Together, the two high-profile incidents also contributed to surges in public interest around school-based policing. After Sandy Hook, National Rifle Association President Wayne LaPierre called for an increase in armed police officers in schools.

Shortly after, President Obama reacted with an executive order that paid to put a new batch of resource officers and counselors in schools. Today, there are about 19,000 sworn police officers stationed in schools nationwide, according to U.S. Department of Justice estimates. In fact, three of the nation’s five biggest school districts employ more security officers than counselors.

The shooting at Sandy Hook also prompted stricter gun laws in Connecticut, New York, and Virginia. And after a deadly high school shooting in 2014 in Oregon, Obama highlighted stricter gun control measures enacted in Australia after a mass shooting left 35 people dead.

“A couple of decades ago Australia had a mass shooting similar to Columbine or Newtown, and Australia just said, ‘Well, that’s it. We’re not doing — we’re not seeing that again,’ and basically imposed very severe, tough gun laws, and they haven’t had a mass shooting since,” Obama said. “I mean, our levels of gun violence are off the charts. There’s no other advanced, developed country on earth that would put up with this.”

While both parties have used tragedies in public schools to frame their stance on the gun control debate, discussions at the DNC Wednesday were near opposite from those last week at the Republican National Convention.

At the Cleveland event, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump painted a picture of an out-of-control crime wave in America. But as The Washington Post has highlighted, America is safer today than it has been in decades, despite an uptick in homicides in some major U.S. cities in 2015. But homicide rates in the U.S. do outpace most other developed countries, a point Democrats have been quick to highlight when discussing gun control.

In California, Gov. Jerry Brown signed legislation in 2015 that would ban carrying concealed guns on school and university campuses following a shooting at Umpqua Community College in Oregon, where nine people were killed. During an October 2015 campaign event in Tennessee, Trump said the shooting wouldn’t have been as tragic had the teachers been armed.

“By the way, it was a gun-free zone,” Trump said. “Let me tell you, if you had a couple teachers with guns in that room, you would have been a hell of a lot better off.”

Despite all the focus on violence in American schools, a May 2016 report from the U.S. departments of Education and Justice, crime in America’s K-12 schools has declined over the past two decades. And while tragic school shootings grab national headlines, less than 3 percent of youth homicides occur at school. During the 2012-13 school year — the most recent data available — there were 53 school-associated violent deaths, including homicides and suicides, in K-12 schools.

“The data show that we have made progress; bullying is down, crime is down, but it’s not enough,” Peggy Carr, acting commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, said in a news release in May. “There is still much policy makers should be concerned about. Incident levels are still much too high.”

— Mark Keierleber (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Editor’s note: In his appearance at the DNC Wednesday night, former NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg made it clear he was appearing as an independent, and said he typically disagrees with Democrats on some key issues — notably deficit reduction and education reform. The comment elicited scattered boos in the arena. Below, Matt Barnum reviews why that rift on education may exist, and re-examines what Bloomberg did in terms of reforming New York’s schools — the most extensive effort this century to reform a large American urban school system.

In endorsing President Obama for re-election in 2012, outgoing New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg praised Obama’s efforts on a handful of specific issues, including climate change, gun control, same-sex marriage, and school reform.

Bloomberg, who won control of the city’s schools early in his tenure, strongly supported the president’s education policies, writing, “[Obama’s] Race to the Top education program — much of which was opposed by the teachers’ unions, a traditional Democratic Party constituency — has helped drive badly needed reform across the country, giving local districts leverage to strengthen accountability in the classroom and expand charter schools.”

When Bloomberg speaks tonight at the DNC, however, he will address a party and endorse a candidate that may be signaling an intention to break from Obama’s reform legacy — as well as from Bloomberg’s mayoral record.

When the billionaire media mogul entered office in 2002, New York City’s Board of Education had long been derided for what many saw as poor performance and disorder. Bloomberg successfully sought authority over the system and appointed Bill Clinton’s former White House counsel Joel Klein. The decision was informed by Klein’s prosecution of the government’s antitrust case against Microsoft in the 1990s; Bloomberg believed that a proven trust-buster, despite a lack of educational experience, was the best choice to reform the city’s mammoth Department of Education.

Under Klein and Bloomberg, New York City rapidly implemented a series of aggressive reforms: closing down low-performing schools, backing the expansion of charter schools and small schools of choice, making it tougher for teachers to receive tenure, retaining elementary school students who failed state exams, raising teacher pay and connecting it to school performance, and grading schools on an A–F scale based largely on standardized test performance.

Subsequent research showed encouraging results for many of these initiatives. Teacher quality seemed to improve as tenure decisions became stricter; schools with an F letter grade got better; small schools boosted high school graduation and college enrollment; charter schools improved test scores; school closures led more students to graduate; retained students did better on tests; new teachers, particularly those in high-poverty schools, had better qualifications; schools in the city were funded more equitably.

But Bloomberg’s policies faced fierce resistance from teachers and their union; the city’s Democratic political establishment, which had close ties to the union; and community groups opposed to the closing of their neighborhood schools and an emphasis on high-stakes testing.

Some argued that school closures destabilized communities and that the city’s high school choice policy was inequitable. Bloomberg’s seemingly off-handed selection of publishing executive Cathie Black to replace Klein was widely derided and she resigned after less than a year. The city also ended its school-based teacher performance pay plan when it failed to lead to achievement gains.

Many criticized what they saw as the administration’s top-down decision-making. For instance, after school board members appointed by Bloomberg said they might vote against a grade retention plan that he supported, the mayor promptly fired the dissenters. And although supporters of Bloomberg hailed record graduation rates, growth on federal tests lagged behind other big cities between 2005 and 2013.

Bloomberg’s successor, current mayor, Bill de Blasio, campaigned on (and subsequently kept) promises to roll back some of Bloomberg’s policies, including eliminating letter grades for schools and curtailing school closures.

Bloomberg is known for speaking his mind. Which then begs the question: will he mention education policy — a rarely seen hot potato in the campaign and at the convention — when he steps to the podium tonight, and use his moment in the spotlight to make the case for his brand of school reform?

Disclosure: The 74 is partially funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, which was founded by Michael Bloomberg.

— Matt Barnum (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

When the DNC does get around to talking about education, I hope they won’t forget the kids who don’t make it to — and through — school

After a painful week observing the Republican National Convention — the fear mongering and the eerie feeling that none of the speakers were addressing me as a black woman — I’m relieved to now be watching the Democratic National Convention. While still political theater, I expect to observe something a little more familiar and directed at my interests.

I have to admit, though, that after two nights, I’m apprehensive about how education will really shape the DNC conversation. If the campaign thus far is any indication, how we educate our nation’s children is likely to receive little mention as things wrap up in Philadelphia. And if it does, I anticipate testing, opting out, teacher evaluation, and other more popular (or political) education topics will be the issues that receive airtime.

I might not agree with what is said, but at least the topics will come up and we can argue the merits. What is less likely to be mentioned is the over 5 million opportunity youth — 16-24-year-olds who are disconnected from school and work — and what is needed to create post-secondary pathways that allow them to access education and careers.

Clinton’s “Breaking Every Barrier Agenda” does include investments in pathways for these young people, but what does it say about us as a country when mention of our most challenged young adults doesn’t elevate to the level of national discourse — when one out of seven young people are an afterthought to our education conversations and policy priorities?

I’ve spent much of the past several years working with and for young adults who’ve veered away from traditional pathways. They are smart and determined, but they need alternative on-ramps to success. Many employers — through The Grads of Life campaign and 100,000 Opportunities Initiative — are working hard to expand access to education and employment for opportunity youth. It may be a big ask, but I would like those of us who are in the business of fighting for educational equity to step outside of our comfort zones to add this group of young people to the list of children for whom we fight.

Maybe adding our voices and energy to the equation could give this issue a boost and generate political will for Clinton — if elected — to act on her commitment to these often forgotten young adults. And maybe this issue — which enjoys some degree of bipartisan support — is an area where we can find common ground to lead us towards an agenda that does more to serve all our children.

— Angela Cobb (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

The last few years haven’t been a great time to be a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives — particularly if you’re a Democrat who wants to increase the federal role in K-12 education.

“We’ve been in a political environment on the Hill where there are people who just do not believe that this a national policy issue, [that] education is just all sort of outside of the national purview,” Rep. Joe Courtney of Connecticut said at a Wednesday event in Philadelphia hosted by The Atlantic.

Being relegated to the minority hasn’t kept Democrats from thinking about what they’d like to see, though.

Courtney, for example, wants to see more schools have health centers. Available medical care can help boost academic performance and attendance, he argued. They’re also the “perfect model” to deal with mental health concerns, he said at the event, which was underwritten by the American Federation of Teachers and National Education Association.

Rep. Donna Edwards of Maryland, meanwhile, was thinking bigger. As in, reconfiguring the whole system of school funding, bigger.

“We do have to change the model for funding. If the median household income are $20,000 in one place and home values are $100,000, those schools aren’t going to be resourced in the same way as other communities with half a million dollar homes or even more than that,” she said.

Edwards – who will leave Congress at the end of the year after an unsuccessful bid for Maryland’s U.S. Senate seat – also argued policy has to change outside of education to benefit schools and students. The country has to have paid family and sick leave, and raise the minimum wage, she said.

“On the one hand, we blame the parents who aren’t engaged. You don’t come to the PTA meetings, you’re not engaged in your school, you don’t provide sort of the extras [wealthier] schools get. You have parents working two and three jobs and can’t do that. Raise the wage base so that parent actually can be a better participant in their child’s education,” she said.

The gap in resources and outcomes has real-world outcomes, Edwards said: students she met on the campaign trail in Baltimore know they’re being deprived.

“Kids are so smart. And they know [they’re getting less], and they don’t like it. And they’re pissed off about it. I think we have to have policymakers who get as pissed off as those kids,” she said.

— Carolyn Phenicie (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

This election cycle, both Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have doggedly pursued the youth vote to varying degrees of success. As the Democratic National Convention heats up, those same young voters are on the ground in Philly — some booing, some studying, some showing careful foresight in planning for the risk of arrest.

From an education policy perspective, it’s especially interesting to see how students are lending their voices and talents to the convention conversation. Here’s how some who are currently enrolled are doing their part.

1. Delegates — College and graduate students make up only a small portion of delegates (just 10 of Pennsylvania’s 189, nine of whom support Sanders). Purdue University, Temple University, and Central Michigan University, among others, have highlighted student delegates. One of those delegates, Central Michigan’s Ethan Petzold, cited Sanders’ commitment to universal higher education, a progressive stance he says resonates with other young people, among his reasons for supporting Sanders at the convention. Also making news is Rachel Gonzalez, a 17-year-old senior in high school (high school!) and Philly’s youngest Clinton delegate. On the GOP side, California’s Claire Chiara, a 22-year-old pro-choice, pro-marriage equality UC Berkeley student, made news last week as the youngest delegate at the Republican National Convention.

2. Protestors — Several outlets have reported substantially more protestors at the DNC than the RNC; many are Sanders supporters disenchanted (or perhaps never quite enchanted at all) with both Clinton and Trump, while others support green party candidate Jill Stein. In a July 11 interview with the Chronicle of Higher Education, College Students for Bernie founder Alex Forgue said his group planned to organize a meet-up and connect with other activists during the DNC. The group’s Twitter account links to a schedule of events for protesters to organize around — mostly more traditional marches and convenings, but also a candlelight vigil for the death of democracy).

3. Reporters — There’s no shortage of press at the DNC, or its GOP predecessor — the RNC credentialed 15,000 journalists. Student reporters from across the country are in Philadelphia to cover the drama — a local group has 20 high school and five middle school students on the ground, Temple University’s broadcast program has extensive coverage, and Hampton University has sent 50 public relations and journalism students to both conventions. Aimee Rodriguez, a 17-year-old Chicagoan, is eager to cover the wage gap, while Rowan University Senior Cierra Lewis plans to report on the Black Lives Matter movement.

4 & 5. Summer schoolers and interns — A few higher education institutions have built academic courses around the conventions. Students from Wake Forest University and Gallaudet University (through a partnership with Temple University) have taken their class work on the road. The Democratic National Convention Committee also hosts a group of student interns, whose operational duties include writing memos, greeting visitors, and supporting senior staff.

Through this campaign cycle, Sanders has perfected the art of courting the young college students like many of those in attendance at the DNC. Clinton, on the other hand, has largely remained one Pokémon pun away from really resonating. With so many students engaged and on the ground, the convention could be Clinton’s window to make those connections.

— Kirsten Schmitz (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Virginia Secretary of Education Anne Holton, who is married to Democratic vice presidential candidate Tim Kaine, resigned from her job to focus on her husband’s campaign, Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, who appointed Holton in 2014, announced Tuesday.

Even as she steps aside from her post in the state education department, her leadership in Virginia K-12 education policy could help shape a Clinton-Kaine administration. She enters a campaign that’s largely focused on race and justice, just as her own time in the national spotlight began amidst a fierce school integration battle in Virginia.

Virginia lawmakers had for years waged a calculated “massive resistance” campaign to prevent public school desegregation after a federal district court judge ordered a citywide busing program in Richmond, where the public schools were sharply segregated. In an unpopular move for a southern Republican, Holton’s father, then-Gov. A. Linwood Holton, escorted his daughter Tayloe to a previously all-black public school — an historic moment that was captured in an image on the front page of The New York Times.

On that same morning in 1970, the state’s first lady, Virginia “Jinks” Holton, escorted Anne and her brother, Woody, to a formerly all-black middle school.

“We did all the things normal middle-schoolers do, but it was my first chance to get to know students whose lives were pretty different from mine, and that was invaluable,” Holton said in a 2015 interview with the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “The chance I was given to make a difference in the larger movement toward racial reconciliation in the South left its mark on me, starting me on the path toward a career in public service.”

Yet as videos of police officers shooting unarmed black men grab headlines, and the Black Lives Matter movement landed a spot on the Democratic National Convention stage, segregation in American public schools is growing. The number of K-12 public schools with high percentages of poor and black or Hispanic students grew from 9 to 16 percent between the 2000-01 and 2013-14 school years, according to an April report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. More than 75 percent of students in these schools were black or Hispanic and eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

In Virginia, “significant and rising shares” of black students attend schools that are “intensely isolated by race and poverty,” according to a 2013 report by The Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 2010, 16 percent of black students were enrolled in schools where white students made up less than 10 percent of the enrollment — up from about 12 percent in 1989.

Before becoming a senator, Kaine previously served as the governor of Virginia, lieutenant governor, mayor of Richmond, city councilman, and a civil rights attorney. Before taking the lead at the Virginia Department of Education, Holton was a Legal Aid attorney representing low-income families and a juvenile and domestic relations district court judge. Holton spearheaded foster care reform in Virginia during her husband’s time as governor. The couple’s three adult children — Nat, Woody and Annella — attended Richmond public schools.

Kaine has said career and technical education is his “main educational priority,” though he’s also advocated for universal preschool. Holton worked to reform standardized testing while running the Virginia Department of Education.

Holton, who graduated from Princeton University and Harvard Law (where she met Kaine), told the Richmond Times-Dispatch that poverty is “certainly one of the biggest” challenges Virginia schools face, while pointing to accountability as second.

“We’ve gotten to a point in a lot of our schools where we’re squeezing the joy out of teaching and learning,” she told the newspaper. “So finding the right balance (between accountability and flexibility) is equally a big challenge.”

— Mark Keierleber (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Democratic vice-presidential nominee Tim Kaine supports individualized teaching, pre-K, and career and technical education, according to a lengthy blog post he wrote for Education Week in 2013.

The essay, apparently the product of significant time and thought, clocks in at well over 4,000 words and provides insight into Kaine’s educational philosophy. I pored over it so you don’t have to; here are the eight takeaways you need to know:

1. Individualization — without a ton of specifics: Kaine believes that one of the keys to improving schools is tailoring learning to the specific student. “We don’t live in a ‘one size fits all’ world and our education system should reflect that. And with new technology tools, we have a much greater ability to have students self-pace with the assistance of teachers,” he writes.

In addition to technology — which has a mixed track record of improving student outcomes — Kaine also wants something like Individualized Education Programs, which spell out the services students with disabilities receive to meet academic goals, expanded to all kids. It’s not clear what this would look like in practice, however.

2. Avoiding the polarized debate on school choice: Kaine explicitly avoids arguments about charter schools or vouchers, saying only, “We know we have to be stronger, but much of the policy debate seems stale to me. Is better high-stakes testing, or charter schools, or more dollars invested the best we can do in terms of educational innovation?”

3. With Clinton on early childhood education: Kaine, like his running mate Hillary Clinton, is a big fan of intervening early in children’s lives, citing the work of economist James Heckman to argue that pre-K is a worthy investment. “There is no question that there is a higher public return on investing in education for a student from age 4 to 5 than from age 17 to 18,” he writes.

4. A surprising critique of elementary school testing: Kaine is a not a fan of “high-stakes testing” (a phrase he uses multiple times), saying it takes up too much time and may drive teachers from the profession. Still, he says, “I see value in having standards and having periodic assessments to see whether students are meeting standards.”

After years of complaints that No Child Left Behind squeezed out subjects other than reading and math, Kaine’s criticism of testing in the early grades is unique — he argues that there is too much focus on social studies and science tests. (Federal law only mandates math and reading tests, but Virginia also has had science and social studies tests in elementary school. The state reduced their frequency recently; Kaine’s wife, then-Virginia Secretary of Education Anne Holton backed this move.) In his view elementary schools should be “simply about attaining math and language literacy.”

Kaine goes on to say, “Making young kids memorize historical facts and figures or struggle with science concepts so that they can pass subject matter tests in those areas is counterproductive.“

This criticism breaks from the common argument that No Child Left Behind squeezed out subjects other than reading and math; with respect to Virginia’s tests, at least, Kaine seems to argue the opposite. Adherents of E.D. Hirsch’s ”core knowledge” theory — which posits that a student’s reading ability is based on knowledge of important facts, including in science and social studies — will surely disagree with Kaine’s skepticism about emphasizing those subjects in the early grades.

5. A broad curriculum in upper grades: Kaine views curriculum beyond math and reading in later grades much more favorably. He explains how his three children, all of whom attended public schools in Richmond, benefitted from music, creative writing, and art — subjects he worries may be undervalued due to “testing mandates.”

“Creativity, teamwork, communication — these are real and meaningful skills for life success,” he writes. “Arts and music education promotes these skills.”

6. Social scientists may cringe: In criticizing what he sees as over-testing, Kaine writes, “mandated tests occur every year, and there are often multiple tests each year. But as our student performance on nationally and internationally normed tests (like NAEP and PISA) show, the fixation over repetitive state testing is not producing better results.” Education researchers will not be fans of this claim: test score data are not an appropriate tool for evaluating specific policies. In fact, studies have found that test-based accountability has improved student achievement in math.

7. Thumbs up to career and tech ed: Kaine praises the expansion of career and technical education in Virginia’s high schools. He argues that they can improve students’ motivation and prepare them for careers after high school without detracting from traditional academic subjects. Recent research from Arkansas backs up this view.

8. Kaine hearts teachers: “I am amazed at how much good teachers give, in the classroom and out,” Kaine writes. He says he is a “huge supporter for regular teacher evaluation” but worries “when I hear policy debate about teachers, if often seems that fundamental goal is to figure out how to get rid of bad teachers.” Like his running mate, he seems skeptical of tying test scores to teacher evaluation, saying “such an effort could make teachers want to avoid serving our neediest kids.”

Kaine concludes his essay by arguing that teachers need better professional development and pay. “At the national level, we should show how teacher compensation practices in this country stack up to the ‘best in class’ education systems worldwide.”

— Matt Barnum (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

The first day of the DNC was about unity. Sign after sign read: “We are stronger together.” Michelle Obama and Bernie Sanders argued passionately for a united party and a united country. Last night, the “Mothers of the Movement” gave Clinton their support because they say she knows black lives matter and that together we can build an America that works for everyone.

Yet until Bill Clinton highlighted Hillary’s work investigating private academies in Dothan, Alabama last night, addressing the divisions in our public schools – the most racially divided domain in the country – has been hardly mentioned.

Today, over 60 years since Brown v. Board, our schools are more segregated than ever. The vast majority of students attend racially isolated schools. And worse, students of color go to schools where most of the students are low-income.

The consequences of this are real. And they are severe.

Attending a segregated school doesn’t only mean the school lacks diversity. It also almost always means that the school is under-resourced, the building is dilapidated, and most teachers are inexperienced and underqualified. Forget high-quality curricula or college-preparatory work, these schools fail to provide even the basic elements of an education.

But despite these facts, we never talk about segregation. Why? Because it’s hard. Because it is painful. And because it forces us to face the ugly truth of decades of unjust policies and practices. The truth is our education system discriminates against students of color.

Desegregation was a powerful solution to our inequitable system. From 1971 to 1988, the achievement gap in reading between black and white students dropped from 39 points to 18. And, even though it was required by law and incredibly successful, we gave up on it in the late 1980s. Since then, court orders have lapsed and once again we operate separate, and unequal education systems.

With Clinton and Kaine, maybe that will become an even larger federal priority.

As Bill Clinton recalled last night, Hillary cut her teeth with Marian Wright Edelman of the Children’s Defense Fund. She fought against southern resistance to school integration. She’s seen firsthand the pain and the promise of breaking down racial barriers and ensuring all students have access to the best schools.

On that score, she’s found a good match in Tim Kaine. During his first speech as a vice presidential candidate, Kaine spoke at length about the virtues of school integration. His father-in-law was the governor who forced Virginia’s schools to integrate. His wife – who just yesterday announced her resignation as Virginia’s secretary of education – was among the first students to attend integrated schools in the state.

Michelle Obama was right: we need a leader who is worthy of America’s greatness and worthy of our children’s promise. Whoever wins in November, hopefully he or she will understand that America’s greatness comes from its willingness to confront its own failings, and to work together to do better for our kids.

— Max Marchitello (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)

Bill Clinton, speaking not in his role as former president but as the candidate’s spouse, talked up his wife’s lifetime of work fighting for children, part of Tuesday night’s broader theme focusing on Hillary Clinton as the “change-maker” America needs.

One of those campaigns for change, in fact, caused an Arkansas politician to quip that the state had “elected the wrong Clinton,” the former president and Arkansas governor said.

Bill Clinton pulls off a presidential first: a first lady speech delivered by a man: https://t.co/1VWq8E0fcH pic.twitter.com/eO3svMFCi9

— New York Magazine (@NYMag) July 27, 2016

Bill Clinton detailed Hillary Clinton’s time with the Children’s Defense Fund after law school, working to expose private segregated schools in the South that illegally benefitted from federal tax breaks.

Hillary Clinton posed as a white parent seeking to send her son to a segregated school. When an administrator admitted the school didn’t take black students, “She had him,” Bill Clinton said. “I’ve seen it a thousand times since.”

Hillary Clinton also joined forces with a group in Massachusetts to figure out why there was a discrepancy between the number of children listed on the census and the number of children enrolled in school. The missing students, it turns out, were disabled, and schools wouldn’t educate them. That research became the impetus for the law known today as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which guarantees access to a free, appropriate, public education in the least restrictive environment to every child with a disability.

The former president noted that all of his girlfriend-at-the-time’s work in law school — including efforts to better identify child abuse at a New Haven, Connecticut hospital and to end the practice of juvenile offenders in South Carolina being jailed with adults — required her to take an extra year to finish at Yale.

That focus on kids didn’t stop when Bill Clinton launched his political career. As governor of Arkansas he set out to improve schools, in response to both a court order and a report showing alarmingly poor results for students. He put Hillary Clinton in charge of the task force investigating the best way to make changes.

“She came up with really ambitious recommendations,” including new standards, counselors in every elementary school, and raises for teachers, Bill Clinton said. He knew the high cost of the program would be a tough sell to Arkansas lawmakers, but Hillary Clinton’s testimony at a hearing swayed them — and was enough to get that “wrong Clinton” zinger from a legislator.

“She is still the best darn change-maker I have ever known,” Bill Clinton said.

— Carolyn Phenicie (Share on Twitter & Share on Facebook)