Denver Backs Down on Huge Gains for Schools After Community Cries Foul Over ‘Inflated’ Report Cards

Corrections appended Feb. 20

Want a crash course in the moving parts that make up a school rating system and the big impacts even small tweaks can have? Look to Denver Public Schools, where lawmakers, district leaders, civil rights organizations, and parents have been engaged in an ongoing dialogue about cut scores, “aimlines,” and other assessment complexities rarely discussed by laymen.

Last fall, the district celebrated a dramatic increase in the number of schools at the top of its celebrated five-color rating system. But community leaders — wise to the ways districts can fudge data — complained that changes in how the ratings were calculated had resulted in “inflated” scores that masked how poorly many students were reading.

The district backed down.

“Parents rely on the accuracy of the district’s school rating system, and providing anything short of that is simply unacceptable,” a group of civil rights and community leaders wrote in a letter to DPS leadership. “Specifically, the district is significantly overstating literacy gains, which distorts overall academic performance across all elementary schools.”

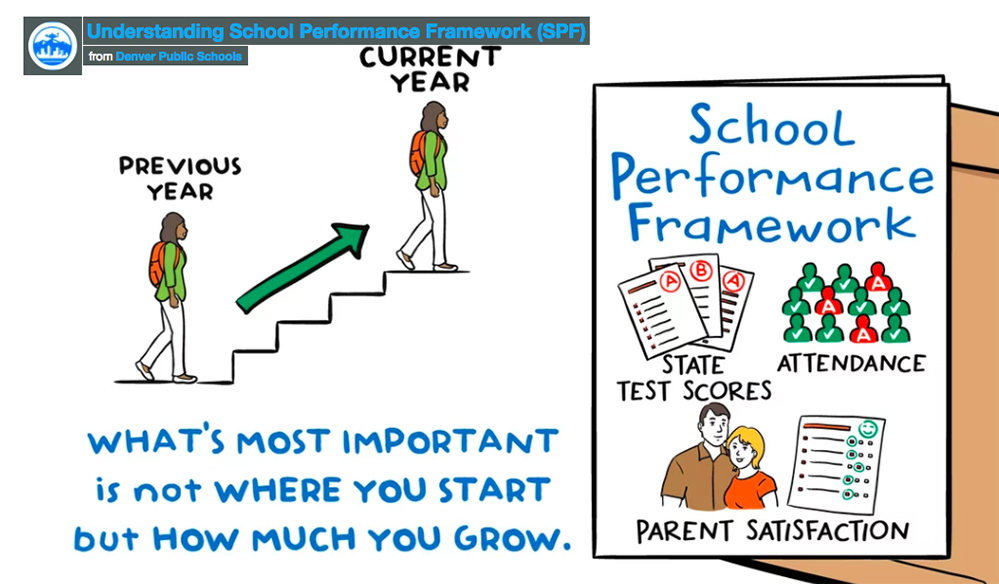

On February 12, district leaders presented Denver School Board members with an overview of their plan to address the community’s concerns about the School Performance Framework, a ratings system that is intended to drive everything from equity in policymaking to families’ choice of schools. The changes won’t apply to a controversial set of ratings released last fall but will be used to calculate school ratings for 2018.

“I’m pleased with how [district leaders] have responded to our concerns,” said Papa Dia, founder and executive director of the African Leadership Group and a signatory to the letter. “We wanted to make sure parents would get accurate information.”

The controversy began in October, when district leaders released the 2017 ratings, which showed a notable increase in the number of schools designated blue and green, the two highest positions on the school-quality scale. The number of Denver’s more than 200 schools earning this distinction rose from 95 to 122, a feat district leaders initially attributed to strong academic growth.

Another nine schools would have scored blue or green had they not fallen short on one element of the rating, the gap between traditionally underserved students and their affluent, white classmates. As in many places, Denver’s students of color, students with disabilities, and English learners aren’t experiencing the same academic growth as their more advantaged peers.

Unlike in many urban districts, however, the conversation about school quality that’s taken place in Denver has equipped community leaders to understand the highly technical elements of the different streams of data the district uses to evaluate schools’ progress. Dia’s group, for instance, monitors school board meetings and organizes several education-related grassroots campaigns.

Made up of a complex blend of school performance indicators, the ratings are extremely important. Parents use them to select schools. They affect school budgets because funding in Denver follows individual students. And schools that consistently score red or orange, the lowest tiers, may be closed or handed to new leadership.

The district’s willingness to “disrupt” underperforming schools and to create new and innovative programs has been widely credited with a decade of solid performance gains. Yet after the 2017 scores were released, DPS leaders said that given academic gains and declining enrollment, for the first time in years they would not be soliciting proposals for specific types of new or turnaround schools and would not provide facilities.

Only one school was slated for closure — at the time, a hot-button topic in school board campaigns in neighborhoods that were home to schools rated red.

Reaction from the community was swift, with critics arguing that changes to the way ratings were calculated masked problems in students’ reading abilities. Unlike most Colorado school districts, DPS does not use the state’s system for evaluating schools. Denver reports the data the state requires but adds some factors, including early literacy tests administered to pupils in grades K-3.

Last year, scores on these iStation assessments played a bigger role in schools’ ratings. For third-graders, however, many schools had large discrepancies between the number of students who scored at grade level on the early literacy assessments and those who did well on the state’s “gold standard” exam, the PARRC. In one school, Farrell B. Howell, 74 percent of third-graders passed the iStation while only 11 percent passed the PARRC exam.

Further muddying the waters were cut points, the bars that assessment administrators set for deciding what qualifies as passing on a given test and how many students must pass for a school to earn a particular rating. Sometimes this threshold is determined by the state and sometimes by the district.

This kind of complexity is the reason some policymakers favor A–F or green-to-red report cards for families, while others argue that the differing measures are too nuanced to be reduced to a single score.

Denver’s color-coded system for holding schools, which operate with unusual freedoms, accountable has drawn national praise — and the 2017 scores were met with concern that the district’s commitment to the strategy was softening.

Criticism was more blunt at the local level. In December, six civil rights and community organizations, including the NAACP and the Urban League, delivered a letter to Superintendent Tom Boasberg demanding that the district correct the “inflated” ratings immediately, before the annual school choice window that opened in February.

Boasberg demurred, saying it was unfair to move a goal so late in the process. Instead, DPS sent individual reports to parents of students who took the early literacy tests, explaining each pupil’s progress in reading.

And then, at the February 12 board meeting, district leaders presented plans to address the criticisms of the 2017 ratings system.

“I think our involvement holding their feet to the fire, it did make a difference,” said Dia. “We look forward to a long-lasting relationship.”

Corrections: One school, Cesar Chavez Academy, was closed last year. Denver Public Schools solicited proposals for new schools but, unlike previous years, did not seek specific proposals, e.g. for a particular type of school or a particular neighborhood.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)