Dear Adult Leaders: Provide Resources By 2022 to Train & Support Teachers to Build School Environments that Can Tackle Racism and Discrimination

This piece is part of “Dear Adult Leaders: #ListenToYouth,” a four-week series produced in collaboration with America’s Promise Alliance to elevate student voices in the national conversation as schools and districts navigate how to educate our country’s youth in a global pandemic. In this series, students write open letters to adult leaders and policymakers about their experiences and how, from their perspectives, the American education system should adapt. Read all the pieces in this series as they are published here. Read our other coverage of issues affecting young people here. This week’s letters focus on the issue of race and racism in schools.

Dear Dr. Angelica Allen-McMillan, Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Education,

I had my first Asian teacher this year after 11 years in our public school system. I didn’t quite recognize this fact or its weight at first — to have a teacher who looked like me. But as the year unfolded, I found myself able to open up about societal and family stress that had often left me feeling isolated with no one who could fully understand the complexities of the pressures I was navigating.

Prior to those two classes taught by an Asian teacher, Legal Theory and Advanced Placement United States History, most of my school-based encounters with the topics of racism and discrimination were skirted around, or the short conversations would barely breach the surface of what needed to be said and discussed.

She did not do this. When the corruption of the justice system came up as we analyzed the cases of O.J. Simpson and Khalief Browder, she did not hesitate to discuss race and juries, mass incarceration, and the role of money and power in determining sentencing. She never told us what to believe, but whenever a student shared an unwavering opinion, she would ask each person questions that went to the root of why they believed their firm assertion. The result? A class of confident, assertive Law and Public Service Program students were forced to confront their own biases, suburban experiential limitations, and the possibility of alternate worldviews, without ever feeling disrespected or silenced.

My teacher is short, loud and funny. She is blunt in a way that most teachers hesitate to be, because of the pressure of potential conflicts and accusations of bias that can arise from misspeaking or misinterpreted words. She may share her opinion, but she never centers her own as a matter of truth invalidating ours. Instead, she asks us to discuss issues, she asks for “whys,” and she challenges us to look beyond the ideological security of our bubbles and search for broader context.

Part of her ability to speak about race and other partially “taboo” topics in the classroom comes from her identity as an Asian teacher — an underrepresented minority in the educational field. For her, as well as for me, topics of race and discrimination are far more proximate to life than vague references in textbooks. Her experience teaching for years in an urban public high school (before she came to our suburb of fewer people than horses) cemented her understanding of the realities of the role of race in the lives of students, and the need for social issues to be given time to process within the classroom.

These types of life experiences that facilitate effective teaching cannot be canned into a magic pill to provide teachers a thorough understanding of how to navigate topics of race and discrimination with students. However, there is far more that we can do for our teachers to create a culture of support and openness that will empower them to successfully integrate relevant social topics and provide an outlet for students to express and critically examine their personal views.

I am lucky to attend school in a district that has begun to embrace equity work, and a school with administrators that encourage the inclusion of relevant current-events discussions, but in an informal poll during the town hall hosted by America’s Promise Alliance and The 74, 64 percent of participating students said their schools had rarely or never provided opportunities to discuss race or racism. If it took me 11 years to experience the type of environment that I wished to see in my classrooms, it is probable that an alarming majority of students in our state go all 12 years without experiencing the social and emotional support necessary to process the chaos of the world they are growing up in.

We have to prioritize training and support for teachers if we ever want to sustainably build school environments that address the need for in-class discussions of racism and discrimination. We have to set aside time, money and care for helping teachers learn how to engage while ensuring that they know they are protected. Progress cannot be contingent on the chance nature of administrators’ views or teachers’ backgrounds; we have to find consistent methods of facilitating this change.

Teachers cannot be blamed for not pushing at classroom norms when discussion of a polarizing topic may risk their livelihoods. Still, we have to recognize that inaction is far more dangerous, with millions of students at risk of isolation and continued existence in harmful environments. This is why teachers need your help in establishing new standards of training and support to ensure that they can gain these skill sets and implement them in the classroom without fearing repercussions for exploring tougher topics in the classroom.

Every step in the right direction is a worthy investment in our future, but the time has passed for inching measures, we need bold action that will address this gap in social and emotional care that millions of students are facing.

By 2022, I ask that you implement state-wide facilitation training for teachers with comprehensive modules that cover methods of mitigating personal bias, language and protocols for teachers to follow when discussing difficult topics, as well as specific recommendations for integration of social issue discussions into regular class time.

I was lucky to have a teacher whose life experience had naturally taught her these skills. I know firsthand what that knowledge brings. It is the reason that I stopped doubting the validity of what I felt everyday as I gathered the courage to speak in a space that seemed to prefer my silence. It is the reason that through student election losses, harassment, the start of a global pandemic, a burning continent, and every other white elephant 2020 had in store, I was able to return to a space where I felt that I could break down the newest emergency and sort through the internal and external anxieties that may have crushed me otherwise.

Our afterschool initiatives can only do so much without the necessary culture change that hinges on empowering our teachers to empower our students. In a world of 24/7 exposure to the worst the world has to offer, it is critical that we provide teachers with the skill sets and resources necessary to both shift the school culture towards a greater sense of connection and to help their students process and cope with the chaos of the world.

Thank You,

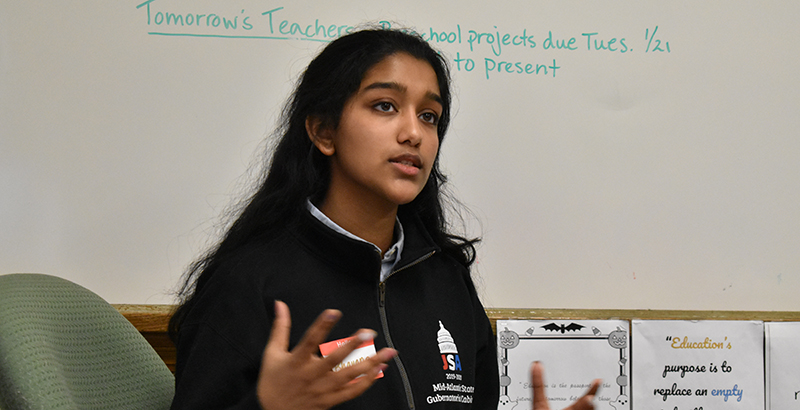

Bhavana Akula, 17

Law and Public Service Learning Center, Colts Neck High School

Colts Neck, New Jersey

This series highlighting the perspectives of American youth is in part sponsored by Pure Edge, Inc., a foundation that equips educators and learners with strategies for combating stress and developing social, emotional and academic competencies.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)