Curriculum Case Study: How One District Tackled 38% Reading Proficiency With Content-Rich Curriculum — ‘It Feels as Though the Ship Has Turned’

This is the sixth in a series of pieces from a Knowledge Matters Campaign tour of school districts in Tennessee. In Putnam County’s Cookeville, a town of 33,000 that is about 80 miles east of Nashville and probably best known as the home of Tennessee Technological University, the district is using a newly adopted, knowledge-rich English language arts curriculum. The district has almost 12,000 K-12 students. Although it is considered one of the higher-performing districts in the state, still only about 38 percent of K-12 students are proficient in reading. Under the most able guidance of Jill Ramsey, supervisor of pre-K-4 teaching and learning (whose email signature has the Ralph Waldo Emerson quote, “Do not go where the path may lead; go instead where there is no path and leave a trail”), the district began fully implementing the Core Knowledge Language Arts curriculum three years ago. Read an introduction to this series here and the remainder of the pieces in this series here.

“Well, I’ll be!” first-grade teacher Stefanie Walker said, in an exaggerated Southern drawl, to her class of eager students sitting cross-legged in front of her on the carpet.

“Say it with me, class; ‘Well, I’ll be!’”

The phrase (which catches on throughout the lesson — and by us visitors throughout the day!) comes from a story, In the Cave, that the children are reading as part of their foundational skills lesson. The story is a “decodable” one, meaning it contains words and sounds the students are practicing. It also provides an opportunity to reinforce how to use commas, quotation marks, exclamation marks and contractions (e.g., “Well, I’ll be!”)

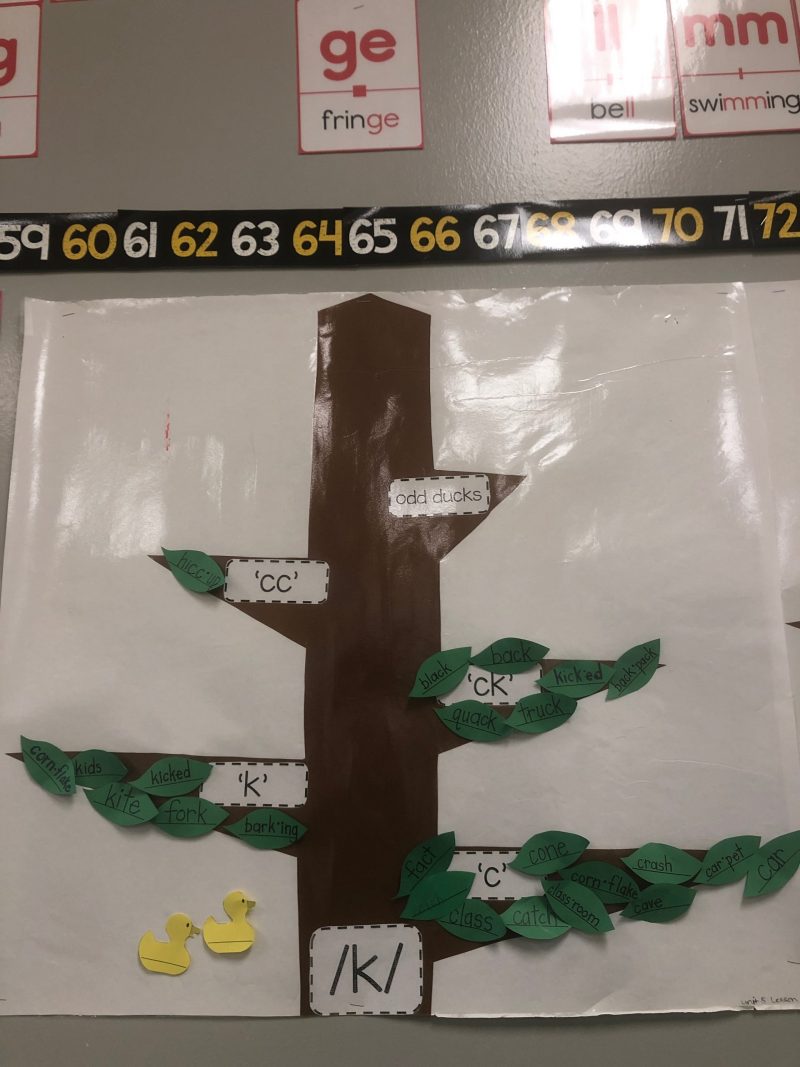

Earlier in the day, these same students — along with all the other first-graders in the building — had participated in a lively lesson about the focus sound for the day: /k/ (like in “cave”). But they didn’t just learn about the one spelling of the /k/ sound; they learned four different ways it’s spelled: “c,” “k,” “ck” and “cc.” The lesson was systematic and explicit, using spelling trees and power bars to teach when and how the /k/ sound is used in our very complex coding system. Students were so excited about finding things all over the room that had the /k/ sound, proving phonics is anything but boring!

A first-grade classroom in Putnam County would have looked very different four years ago. Phonics instruction would not have been explicit, systematic or even consistent from one class to the next, whether down the hall or across the district. Our teachers were spending a majority of their time searching for resources to teach the standards, rather than relying on a strong curriculum to do that work for them. They dedicated so much time to figuring out what to teach, they didn’t have time left to perfect their practice.

We all knew that what we were doing wasn’t working. Many of our children weren’t learning to read. In fact, a large majority — 62 percent — weren’t proficient in reading. That was unacceptable.

With help from our partner TNTP, the district made the decision five years ago this spring to pilot a curriculum that would address decoding while coherently building content knowledge. That was the beginning of a new journey for us. We started small, with 20 classroom teachers in pre-K-2 using the “Listening and Learning Strand” (the knowledge-building component) from Core Knowledge Language Arts, a “comprehensive preschool-grade 5 program for teaching skills in reading, writing, listening and speaking” that “also builds students’ knowledge and vocabulary in literature, history, geography and science.”

It was a heavy lift and a bumpy ride.

“It was a struggle in the beginning because it was hard,” one teacher said. “The other curriculum was easy; we just switched out readers for each lesson.”

But after that pilot year, teachers were already seeing how students were more engaged and excited about the topics they were reading about. This showed up very unexpectedly in their writing; we couldn’t believe how much more they were able to write, and the complex vocabulary they were using, even in kindergarten! Our teachers bought in based on the strength of these results.

In year two, we expanded by adding to K-2 classrooms the Skills Strand of the CKLA curriculum, which teaches the mechanics of reading, like explicit phonics instruction and spelling. We also added to the third and fourth grades the Listening & Learning Strand, which builds vocabulary and broad knowledge in science and history through a series of read-alouds of informational texts. Since then, we have been digging in as an elementary team, deeply studying and learning from the curriculum.

Our literacy coaches have been invaluable to this process. They have become experts, assisting teachers in planning and implementing quality lessons using the curriculum.

Recently, we had the opportunity to host the Knowledge Matters Campaign Tour in Putnam County. Over the course of two days, the team visited three schools, conducted interviews with students, teachers, administrators and parents, and got to watch some amazing lessons. For the past three years, we have seen classroom instruction improve significantly because of strong materials, but I wasn’t sure if others would see it as clearly as we did.

Guess what: They did! Every lesson we watched was beautiful. Teachers were invested in the lessons, bringing them to life as they and their students read about slavery, the planets, geology, inventors and on and on. I was personally on the edge of my seat as I listened to the read-alouds. I thought I would burst with pride, and I’m sure that I shed a few happy tears just watching our kids as they listened to their teacher with such rapt attention while she read about topics that interested them and as they shared with our visitors about what they loved about the “new” way of learning.

Change takes time, but we are encouraged and motivated to continue the journey. At this point, it feels as though the ship has turned, and the throttle is full steam ahead. We know that we have expert teachers who can lead the way for those who are more reluctant.

“Every year we get better. I am looking deeper into every lesson for ways to improve,” one of our teachers said.

“This curriculum levels the playing field,” said another. “It gives students the opportunity to experience things that they wouldn’t normally see because many of them may rarely leave their yard. When you look at student writing on the wall, you can’t tell which students are [special education] and which are not, which are poor, or which are wealthy.” Isn’t this the meaning of equity?

For too long, teachers had to be all things at all times, even creating their own curriculum. But that is not something they were trained to do.

“In the past, our principal would ask us the question, ‘Is this worthy of students’ time?’ And I would spend a lot of time trying to make it worthy,” one teacher said. “Now I know it’s worthy.”

I can imagine there will be many “Well, I’ll be!”s in the years ahead, as teachers learn the curriculum in greater depth and use their teacher knowledge to bring it to life.

Jill Ramsey is the pre-K-4 teaching and learning supervisor for Putnam County Schools in Tennessee.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)