Curriculum Case Study: How a New, Tougher (and Free) Language Arts Program Built Around ELL Supports Improved Literacy in a Town at the Foot of the Great Smoky Mountains

This is the first of a series of pieces from a Knowledge Matters tour of school districts in Tennessee. Lenoir City sits along the Tennessee River southwest of Knoxville and is considered a gateway to the Great Smoky Mountains. Lenoir City Intermediate/Middle School is in its second year of implementing EL Language Arts, a curriculum they selected in part because the science-centric topics appealed to teachers and the robust supports for English language learners were vital, given the rapidly growing number of ELLs in the district. Knowledge Matters asked Brandee Hoglund, principal of Lenoir City Intermediate/Middle School, to write this piece. Read an introduction of this series here and the remainder of the pieces in this series here.

If what you are doing isn’t working, you owe it to your students to make a change. This is the belief that drove our school, Lenoir City Intermediate/Middle School in Lenoir City, Tennessee, to change its English language arts curriculum in 2017.

One of the things we realized when we dove into this work is that we didn’t actually have an ELA curriculum. Our teachers spent countless hours finding and modifying their own materials to teach the standards. Some teachers did this better than others, but none did it well enough to move our ELA achievement scores out of the 20 percent proficiency range.

In fact, our achievement scores had hovered in this range since I was a teacher, in this same building, 20 years ago. Our student growth varied year to year, but it was never enough to move the achievement needle. My assistant principal and I knew we had to do something different.

Unfortunately, we had no money. Since it wasn’t an adoption year for ELA materials, we began researching free open educational resources. Expeditionary Learning, now called EL Education, caught our eye because of its rigor. We presented the curriculum to a couple of seasoned teachers, they came on board, and we — the assistant principal and I — trained the rest of our ELA teachers that summer.

EL Language Arts uses authentic trade books, which we purchased using fundraiser and instructional funds. But we printed out lessons and made curriculum notebooks ourselves.

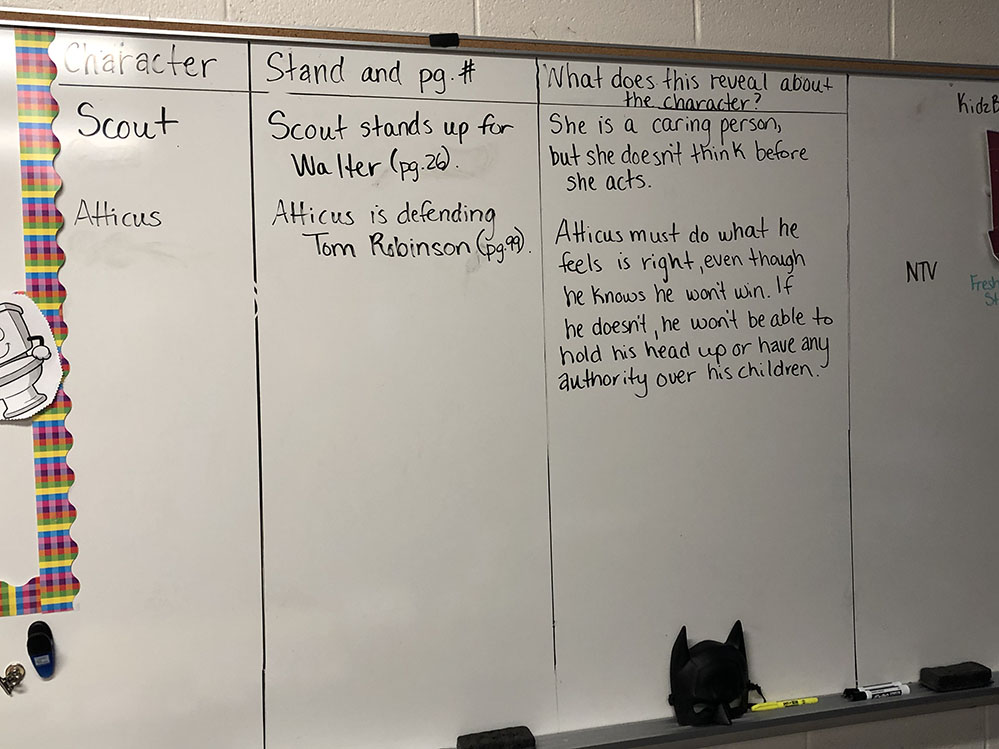

Although our teachers were on board about making a change, they were nervous. I remember one of them being particularly concerned about teaching To Kill a Mockingbird to her below-grade-level students. I encouraged her to just try it and see what happened, and I’ll never forget the day she came back and said, “They can do it!”

In the past we never would have chosen such a high-level text for our lower-level students, and instead would have used one to match their instructional level. Knowing we were leveling the equity playing field for our students is what gave us the courage to press on.

I wish I could say the first year of implementation was great, but the fact is, we tanked! Our achievement and growth scores decreased across all grade levels. The curriculum was great, but our plan was not.

The biggest mistake we made — and I take responsibility for this as the leader — is that we had no idea of the science behind the EL curriculum. It was not until our elementary school got involved with the LIFT network, and our district graciously provided us with professional learning support from TNTP, that we began to really understand the intention and science behind the curriculum. It was then that we began to provide the type of support the teachers needed to be successful.

I was concerned that, in view of the disappointing results after all the hard work that first year, teachers would want to abandon the curriculum. How could these rock star teachers, whose test scores decreased the first year of implementation, not feel betrayed?! But that wasn’t their reaction. They had seen the light and knew the curriculum was what they needed to turn things around. They said, “If you are on the crazy train, then we are on it with you!”

Our second year was a completely different experience. Teachers were required to teach the modules in order, which wasn’t something they even knew to do before, because the curriculum builds on itself. Now that teachers understood the curriculum better and trusted it more, the pacing problems we’d had in year one went away. If a student didn’t master a skill in the first module, teachers knew it would be revisited in a later module with another chance to do so.

People — including some of our own teachers — have worried that comprehensive curricula like EL Language Arts are “scripted,” leaving little room for teachers to make it their own. This is not the case. Sure, the lessons are created for you — but once teachers understand the overarching goal of the module and appreciate how the lessons build, the curriculum encourages adaptations to meet the needs of students.

With the help of TNTP, our external professional learning partner, we implemented a daily planning protocol. This implementation was not easy; in the beginning, it took hours to complete. But my teachers saw the value and leaned in, enabling them to see the backward design of the module and really understand the purpose of each lesson. If you ask them to name the one thing they would recommend to teachers new to the EL curriculum, my teachers would say, “Complete the planning protocol.”

The EL curriculum has transformed ELA instruction in our school. Teachers now focus on instructional delivery instead of instructional design (and creating curriculum from scratch). They have time to analyze student work, diagnose mistakes and misunderstandings, and provide meaningful feedback to improve student work. Because teachers are able to refocus their time, our students are flourishing.

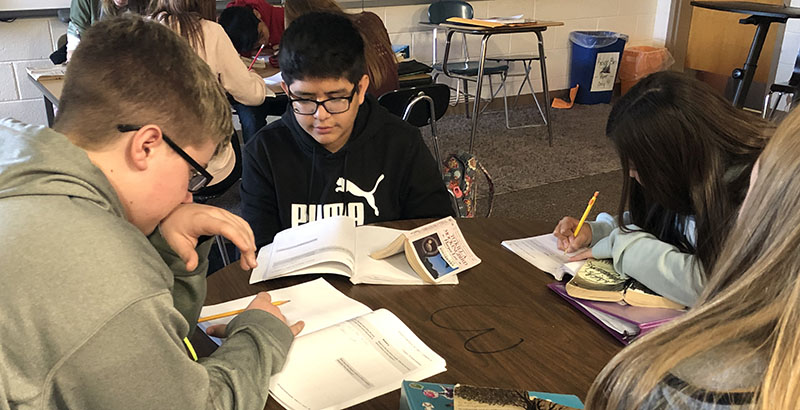

Our students, and I mean all of our students, are able to analyze and write about complex texts. They are able to make connections between multiple texts and are excited to share their thoughts both verbally and on paper.

And our students have a lot to say about EL Education! One young lady told our Knowledge Matters Campaign visitors that she preferred the longer texts: “I like sticking with one thing. Before it was just always something new; this topic one day, another topic the next. How am I supposed to make a connection with the main idea when there’s so little information?” she wondered.

By exposing all students to the same complex texts, we are noticing that students’ perceptions of others are also undergoing change. An eighth-grade student candidly shared that there are people in her class she would have never thought would have known so much about what was being discussed in the texts. Teachers are now seeing that when the expectations are high, our kids will rise to the challenge.

Great teachers deserve great instructional materials, and it is our job to provide that for them. In turn, great students deserve great teaching and curriculum, and our teachers are providing this for our students!

Brandee Hoglund is principal of Lenoir City Intermediate/Middle School in Lenoir City, Tennessee.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)