Curriculum Case Study: How an English Language Arts Program Is Leveling the Playing Field in Classrooms Where the Majority of Students Live in Poverty

This is the second in a series of pieces from a Knowledge Matters Campaign tour of school districts in Tennessee. Sullivan County sits in the northeast corner of the state and is home to almost 9,200 students. The school system has received national attention for the progress it’s made using the Core Knowledge, a comprehensive English language arts curriculum that sequentially builds students’ knowledge of history and science topics as they are learning to read, beginning as early as kindergarten. After four years of strategic implementation, all 11 elementary schools in the district are using the program from kindergarten to the fifth grade. Knowledge Matters asked two principals, Alesia Dinsmore of Rock Springs Elementary and Angie Baker of Central Heights Elementary School — both of whom have been part of the curriculum’s rollout since inception, to share some of their lessons learned. Read an introduction to this series here and the remainder of the pieces in this series here.

Halfway through a unit on the westward expansion this year, a second-grade teacher in Rock Springs Elementary School was conducting a read-aloud of the Core Knowledge text Buffalo Hunters. She posed the question, “In what ways are the steamboat and the locomotive train similar?” One of our most behaviorally challenged students — a young boy who lives in extreme poverty and struggles mightily with anger — was eager to display his knowledge. “The train and the steamboat both run off coal or wood. Both have steam,” he said. “I am like the train. The train has to release steam. It’s like me. Sometimes I get really, really mad and I have to release steam. That helps me calm down or I would explode, just like the train.”

What this young boy demonstrated is the impact that rich and relatable texts can have — and the platform they can provide for the kinds of connections we want students to make. In the past, this classroom might well have been working on a skill like “cause and effect” with a text like Don’t Slam the Door (about the effects of the family dog letting the house door slam). With Buffalo Hunters, not only is the student far more engaged, but also this teacher has more meaningful content to explore, more advanced vocabulary to discuss and more interesting writing prompts to assign.

Over the past three years, our school system has moved from a “1” on the state’s TN Ready Assessment to a “4,” exceeding the state’s growth standard. The percentage of students requiring Tier 3 instruction — intensive intervention, versus general instruction in Tier 1 and moderate intervention in Tier 2 — in ELA has dramatically decreased. We’ve accomplished this with the largely free, downloadable version of the Core Knowledge Language Arts program, supplemented with grant dollars.

Our journey with CKLA has been transformative, helping us to act upon three core beliefs:

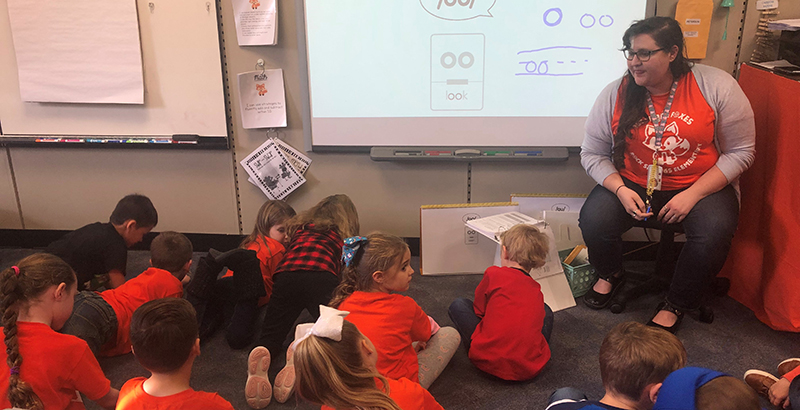

1. Focusing on foundational skills (e.g., phonemic awareness and phonics) instruction;

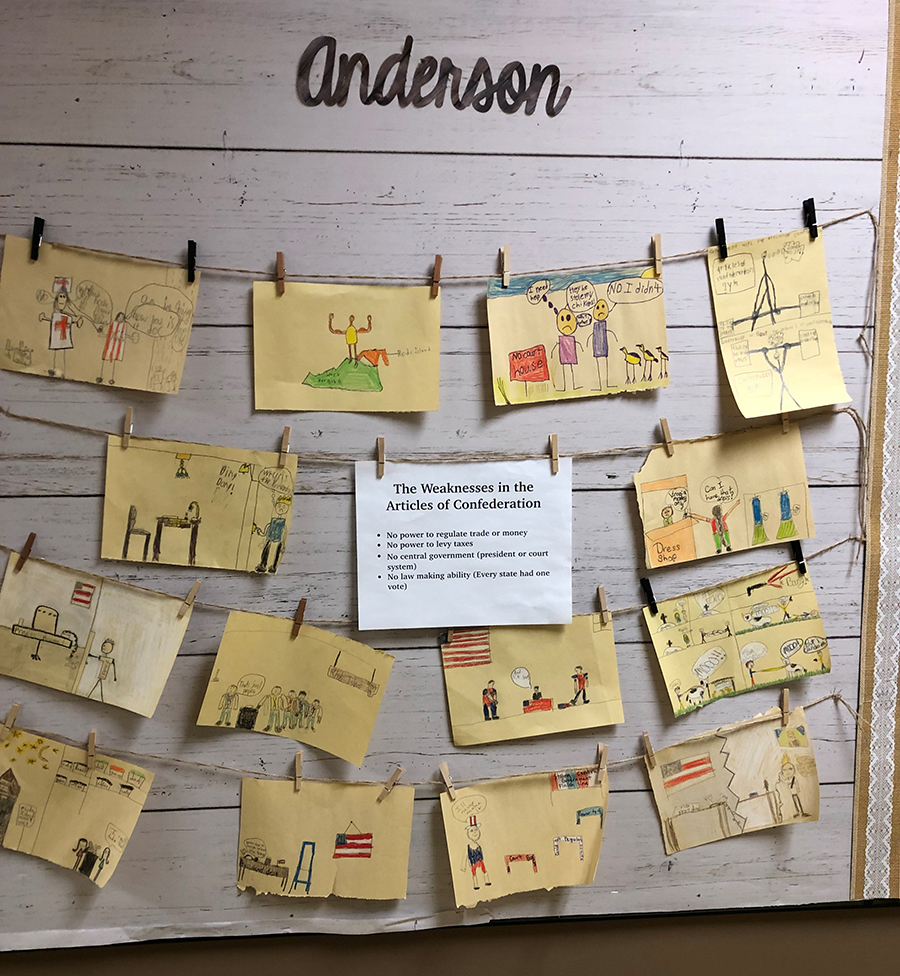

2. Ensuring that the questions we engage in with texts require higher-order thinking versus simple recall and memory;

3. Passing on ownership to students for their work.

In our experience, it is rare to find teachers who don’t believe students can perform to high expectations. The problem is that they don’t know what to do about it; we have not given them an organized way of delivering on their core beliefs.

Over the past three years, Sullivan County Schools has put significant effort into professional learning about those three core actions that have greatly impacted instruction and, consequently, student learning. Those core actions have been instrumental in moving forward our district’s literacy improvement plan.

Prior to the implementation of CKLA, phonics instruction — including writing assignments that required mastery of sound-spelling patterns and sight words — was often isolated and brief. While teachers had a great deal of control over the way they used the block of time carved out for reading instruction, they had little understanding of the power and strength of strategic, explicit phonics instruction. It was rarely connected to any current unit of study and ranged in sophistication from merely sentence-copying to the more sophisticated construction of paragraphs on isolated topics.

Through our work with CKLA, our teachers have been given the requisite training to pass on the code-breaking tools of reading to their students. They’ve learned that while the English language has only 26 letters, these letters represent 44 different sounds (which they are taught how to correctly pronounce in isolation) and make up 150 different spelling patterns. What we have found is that when teachers provide foundational skills instruction that is explicit and systematic, all students have the opportunity to perform at mastery.

The kind of questioning that drives our inquiry of texts — the second core action — has also undergone a considerable shift. Prior to the implementation of CKLA, when we observed teachers, we noticed that questions were designed for a quick student response that didn’t set teachers up for follow-up questions, so they often accepted a weak response and moved on. Now our teachers plan. The curriculum sequences questions for them — questions that develop from the level of knowledge/recall to higher order. As a result, our students are understanding texts at a deeper level and engaging in far more complex thinking about what they’re reading, as indicated by the second-grader who independently likened himself to a steam engine.

We are really just getting started with this work and are now focusing ever more effort on the quality of student responses. In doing so, we are beginning to see students owning more rigorous thinking and articulating their own ideas. Student responses contain details from the text, and they confirm or refine their understandings through collaborative group interaction. Students are developing the ability to incorporate academic vocabulary, defend their response with text evidence and build on each other’s responses respectfully.

Putting the conditions in place where students can take this kind of ownership of their work is the third core action. Prior to the implementation of CKLA, teachers exposed students to texts that, frankly, were not especially rich in content, rigor or vocabulary. The texts they were reading were often written not so much to convey knowledge or mine themes as to teach strategies like “find the main idea” or “cause and effect” — which can be done just as easily with Don’t Slam the Door as it can with a story like Buffalo Hunters. It was difficult for students to make deep connections to these lower-level texts — to, in fact, have much interest in them. Even the read-alouds, presumably at a more advanced reading level, weren’t engaging our students.

But now they are learning about the War of 1812, Greek mythology and westward expansion. They understand the importance of these topics, which are extensions of ones they learned the year before and are the building blocks to other important topics they’ll learn in the years ahead. They are invested in learning because the topics are interesting to them.

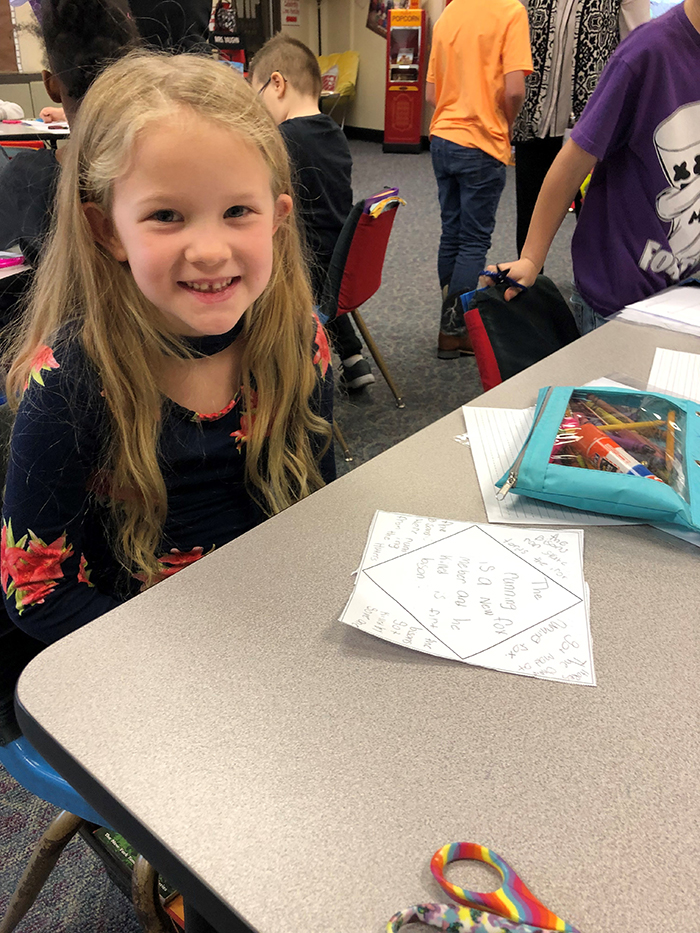

Once again, we want to underscore that this ownership applies to all students in our buildings.

Here’s another recent scene from a second-grade class. The teacher is reading Prometheus and asks her students, “Was the punishment Zeus gave Prometheus fair?” A student responds, “Well, it seems fair to Prometheus, but what about the bird? If the bird comes back every day to eat liver because it grows back daily, would it be a punishment or not? I like steak, but if I had to eat it every day, it might not be a treat anymore. And what about his freedom? He has to be there every day to eat the liver. But, what do you think?” We are all so proud that this young man, who is one of the poorer children in our school and also has special needs, is able to participate in the classroom discussion alongside his peers, making profound contributions to work of the group.

One of the most exciting things for our school community, and for visitors like those who came to see us as part of the Knowledge Matters school tour, is that when you enter our CKLA classrooms, you can’t tell which students might be living in poverty (60 percent), are receiving special education (18 percent) or are homeless (2 percent); you can’t distinguish which are from low or high socioeconomic groups, which have stable or dysfunctional family situations. They are all engaged. They are all responsive. They are all on a level playing field for success.

In Sullivan County, we are learning that their core beliefs about what is possible instructionally need to be backed by core actions — and that those actions need to be supported by strong curriculum and practiced daily. We are thrilled about where this journey is taking our staff and our students.

Alesia Dinsmore is principal of Rock Springs Elementary School in Sullivan County, Tennessee.

Angie Baker is principal of Central Heights Elementary School in Sullivan County, Tennessee.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)