Curriculum Case Study: After a Shift in Curriculum in One Tennessee County, ‘Everyone’s Playing Field Is the Same’

This is the fifth in a series of pieces from a Knowledge Matters Campaign tour of school districts in Tennessee, produced prior to the state’s closure of campuses in mid-March. Sumner County sits northeast of Nashville and is in the first full year of implementing Wit & Wisdom, a curriculum chosen for its rich texts and emphasis on shifting the cognitive load to students, particularly in writing and speaking. Two elementary schools are highlighted here. Vena Stuart Elementary School is the most diverse school in Sumner County, with one of the largest populations of economically disadvantaged students and a rapidly growing number of English learners. Station Camp Elementary School is the largest elementary school in Sumner County, with more than 1,000 students. Read an introduction to this series here and the remainder of the pieces in this series here.

“Who would like to share their vocabulary with our guests?” asked second-grade teacher Karen Carpenter.

Sitting on the edge of their seats, students began calling out: “Injustice!” “Segregation!” “Oasis!”

“Where did you find that word, ‘oasis’?” Carpenter asked. “Can you find it in the text?”

“It’s Dr. Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream speech,” one boy responded. “[It says,] Mississippi will become an oasis of justice and freedom.”

Moments like this — and there are many as we walk through our classrooms — give me goosebumps. They punctuate beautifully our year’s journey to implement Wit & Wisdom in our second- through fifth-grade classrooms.

Overall, Sumner County’s poverty rate is 25 percent, though we have schools like Vena Stuart that exceed 70 percent poverty. Just 46 percent of the district’s students demonstrate reading proficiency. And while Station Camp Elementary School outperforms the district as a whole with a literacy rate of 57 percent, Vena Stuart’s literacy rate is a sobering 28 percent.

“For so long, we’ve said, ‘Kids can’t answer these complex questions; they can’t do this,” said third-grade teacher Stephanie Watkins. “But we’ve seen it in action; they’re brilliant!”

In past years (in the Journeys ELA curriculum we used), our second-graders would have read Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type, paired with Talk About Smart Animals! They might even have sung “There’s a Hole in the Bottom of the Sea.” In contrast, the current module, Civil Rights Heroes, pairs rich texts on Martin Luther King and Ruby Bridges with poetry by Langston Hughes and iconic photographs of the Selma to Montgomery march. The result: Every second-grader in Carpenter’s class knew the importance of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and understood what segregation and discrimination meant. At age 7, they probably have a better understanding of the civil rights movement than the vast majority of the population.

“It’s amazing, the work they can do when we expose them to these complex texts,” said kindergarten teacher Caitlyn Tucker.

Our journey to Wit & Wisdom began during our annual strategic planning meetings in September 2018 when principals discussed the huge burden our teachers were carrying as they backfilled the curriculum to develop their own ELA units. On average, our teachers were spending 12 to 15 hours per week finding materials and developing activities and assessments, building their units around a skill each week — like main idea, drawing conclusions, or cause and effect. Leaders devoted significant time to assessing text complexity and reviewing required planning documents to ensure that grade-level texts were being used.

In response to principals’ concerns, Director of Schools Del Phillips asked me to implement a third-grade ELA curriculum pilot during the second semester (one year ago). The elementary coordinators recommended Wit & Wisdom, and we almost immediately noticed a huge difference in student engagement, which led teachers to embrace the work of learning a new curriculum.

“Successful implementation of a high-quality curriculum requires everyone to coach others and be open to being coached themselves,” Phillips said. “We are building this into our DNA.”

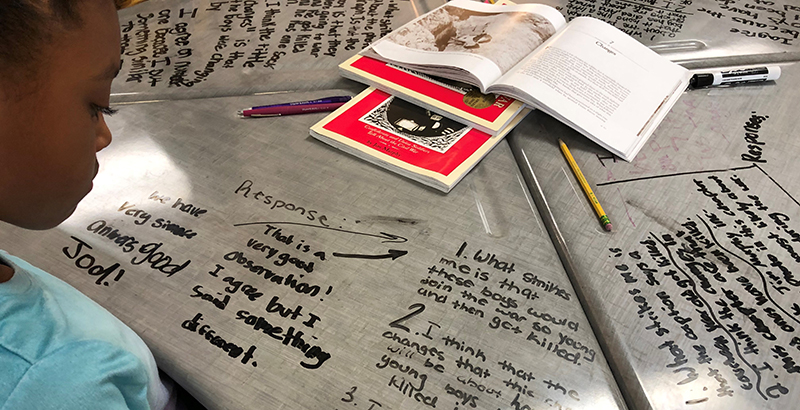

In raising the bar, the cognitive load has shifted from the teacher to the students. In Stephanie Williams’s fourth-grade class at Station Camp Elementary School, students read and researched different colonial occupations from the text Colonial Voices: Hear Them Speak and then predicted whether they would be patriots, loyalists or neutral. The students presented their findings and supported their claims with textual evidence. In each of the classrooms we visited, we saw students — rather than the teacher — driving the work and conversation.

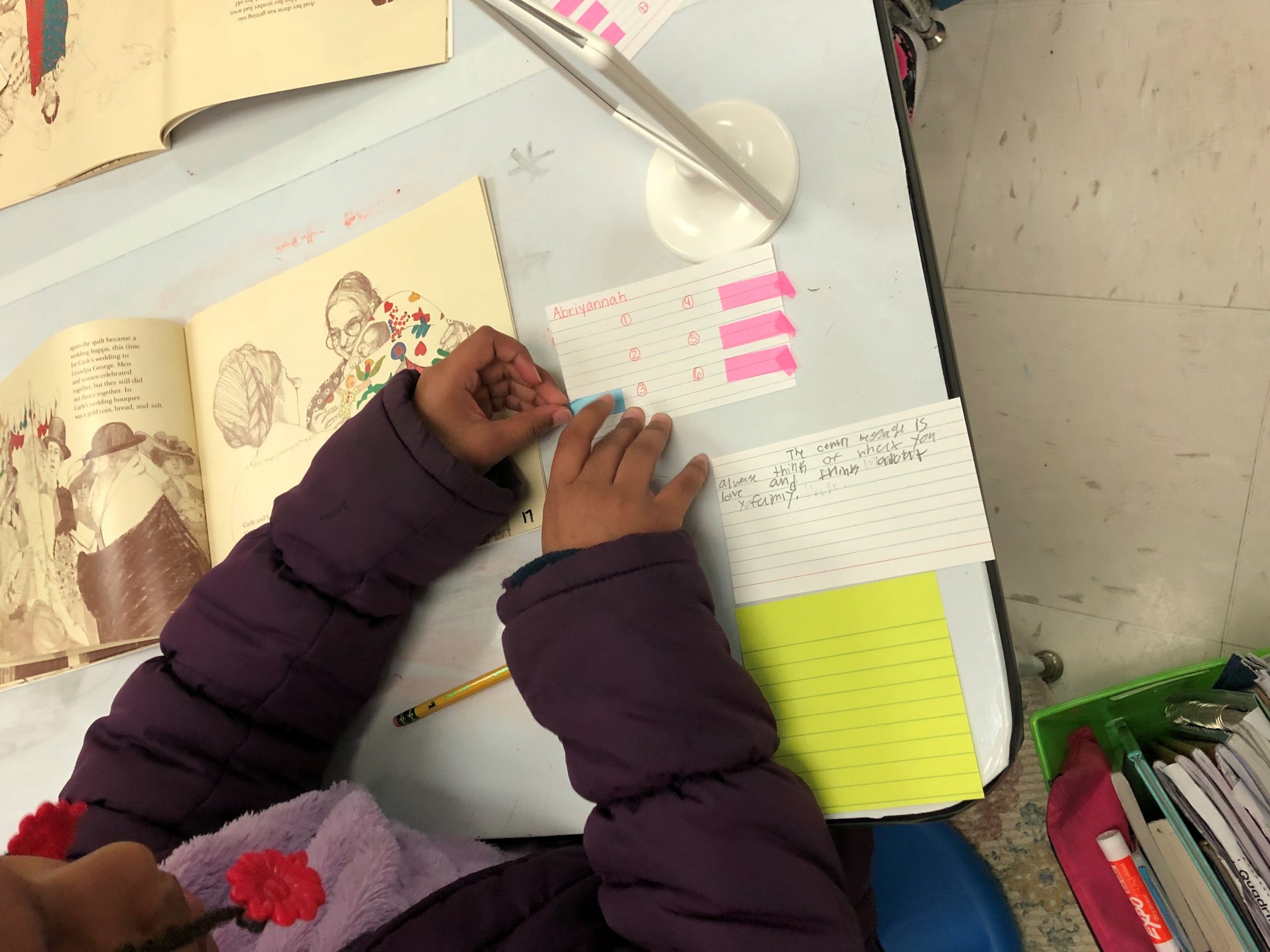

At Vena Stuart Elementary School, as part of a unit on immigration, Jenni Copeland’s third-grade class worked its way through The Keeping Quilt, a story about family traditions passed on through generations. The unit culminates in a Socratic seminar in which students work together to determine the central message of the story. The teacher barely spoke as the students took turns sharing textual evidence to support their claims.

“My students are discussing why immigrants come to America rather than just trying to find the main idea,” the third-grade teacher said.

The shift to a high-quality curriculum is not easy and has required tremendous work by our students, teachers and leaders. While I am proud of the effort everyone in the district has made, the role of our principals has been particularly pivotal. In the past, principals struggled to support their teachers, since each classroom was doing something different. Now they can learn the practices, the procedures and the content of the curriculum and engage in lesson and module study alongside their teachers — which has made their observation and coaching so much more effective.

“Everyone in the district is doing the same thing together. Everyone’s playing field is the same,” Station Camp Principal Racheal Mason said. “We get more support from each other between schools, and it is easier to [get] support from the district.”

Third-grade parent Jonathan Blayney recounted an evening when his daughter and her friends had a polite, intelligent conversation about immigration while eating dinner after soccer practice. Here’s the clincher: The five girls each attended different Sumner County schools, but they were all studying the same unit!

In Sumner County, we believe strongly that our students are capable of significantly more than we have ever asked of them.

“My mantra is that you can tell me you can’t do it. I’ll help you. I’ll show you. I’ll model a lesson. I’ll help you plan, but do not tell me our kids can’t do it,” said Vena Stuart Principal Jessica Adams.

Our students can do it — and Wit & Wisdom is giving them the chance to prove it every day — including at home. Blayney has noticed a dramatic increase in his daughter’s interest in reading over this past year. In the past, he said, reading was a struggle, but now she is making connections between the reading modules and shared interests.

“She knows I love to scuba dive, so she came home talking about reading about Jacques Cousteau and the ocean,” Blayney said. “[These connections] have made her come alive in reading; she’s wanting to bring reading home.”

In student conversations, seminars, group work and writing, we see each day that our kids can do abundantly more than we’d imagined. Our dream now is to keep raising the bar and watching our students push even higher.

Scott Langford is assistant director of schools for instruction for Sumner County Schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)