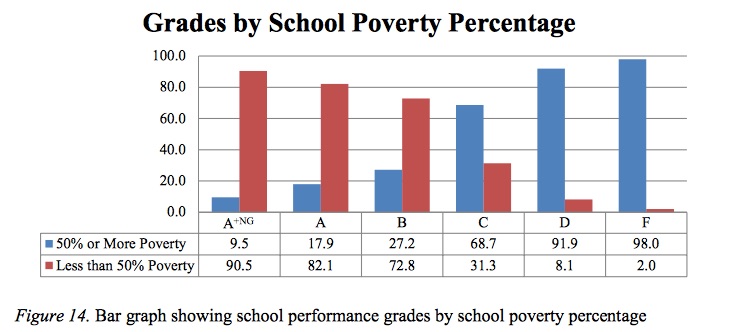

Take North Carolina, where schools with high numbers of low-income students were 50 times more likely to get an F letter grade than schools with low poverty rates.

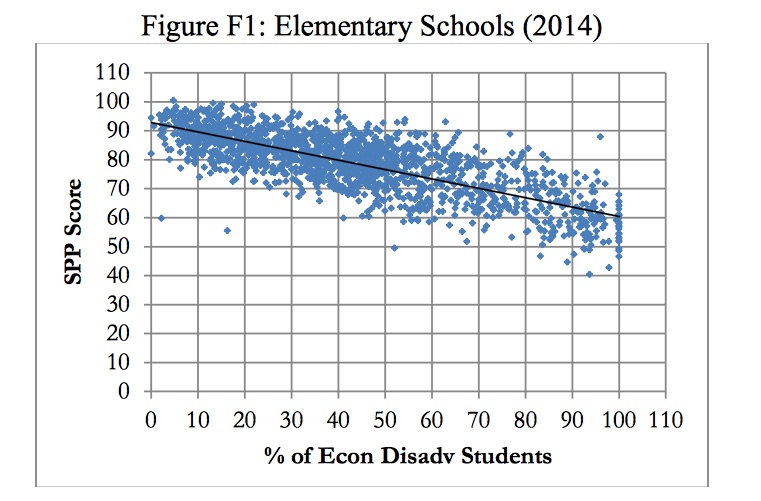

Or look at Pennsylvania.

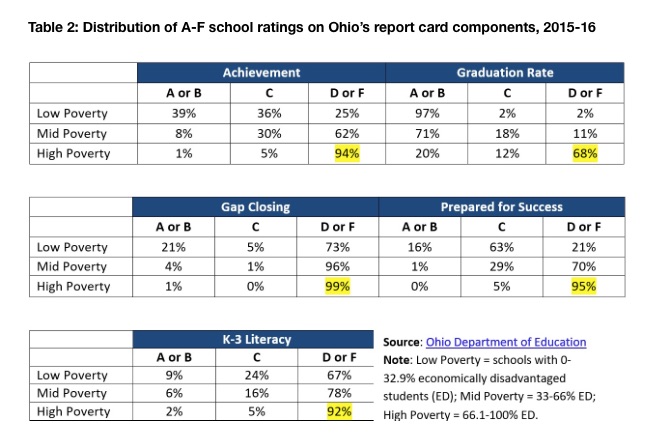

Or Ohio.

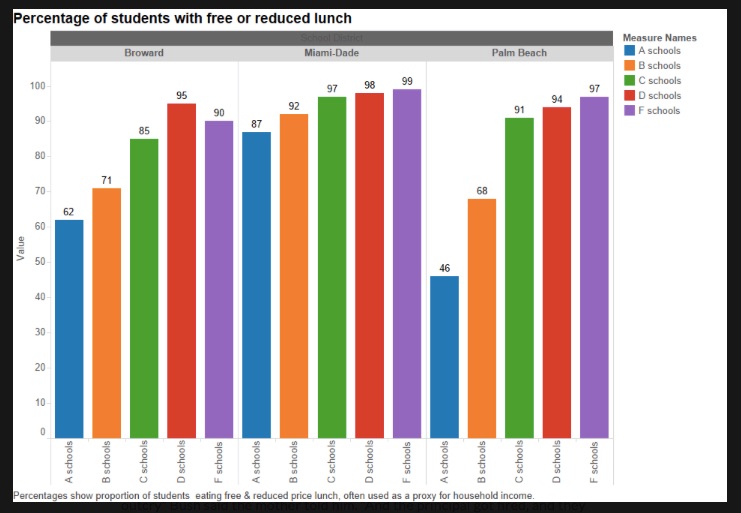

Or Florida.

You get the idea.

As states work to design new accountability systems under the Every Student Succeeds Act, these patterns are likely to persist, at least to an extent. While some argue that focusing attention and interventions on high-poverty schools makes sense, others worry that maintaining such a relationship risks punishing the wrong schools and deterring teachers from working in low-income areas.

The first reaction when looking at this tight association might be that low-income areas simply have significantly worse schools, and that their worse grades reflect that reality.

While there is likely something to that, measures of inequity in teacher quality between schools show that it is actually smaller than widely perceived and is unlikely to explain all or most of the achievement gap between affluent and lower-income students. Large inequities are evident before students even begin school.

One reason that measures of school performance are so highly correlated with poverty is that a common metric is the proportion of students who are proficient on state exams, meaning whether a student meets or exceeds a certain score seen as demonstrating knowledge or skills relevant to his or her grade. Student proficiency is itself closely tied to income.

Researchers generally caution against judging a school by the number of students who score proficient. If the goal is to isolate a school’s impact on student test scores, complicated growth models that measure how much individual students improve from year to year and take into consideration demographics like poverty are preferable, although still imperfect. Progress measures are much less strongly linked to rates of poverty.

To Cory Koedel, an education researcher at the University of Missouri, emphasizing absolute performance measures, like proficiency, risks painting an inaccurate picture of how schools are doing, lumping all low-income schools into the same category.

“There’s huge variation in the growth that kids achieve even among all high-poverty schools,” said Koedel, who studied schools in Missouri. Saying that the vast majority of poor schools are bad masks that, he argues.

“We aren’t sending the right signals to different educational actors about what’s working and what’s not because we’re just basically spitting back to them the poverty of their kids,” he said.

Koedel also said there’s another downside: making it less desirable to work in low-income schools. Such schools often have a hard time getting and keeping good teachers, and other research shows that when schools are labeled “failing,” effective teachers are likely to leave.

“No one wants to go work in a place where you’re told you’re not doing well,” he said. “That is a part of your job satisfaction, and it wears on you.”

Some groups defend the use of proficiency and prioritize measures that are correlated with student poverty.

“We know that without honest proficiency data from an aligned assessment — the single best indicator for measuring college- and career-readiness — school accountability as a lever for excellence and equitable improvement is dramatically undermined,” read a report from the civil rights and education group Education Trust–MidWest in response to Michigan’s draft accountability plan, which includes both measures of achievement and progress.

The group is also critical of the choice to use a sophisticated growth model that compares how much students improve relative to peers who start out at the same achievement level.

“Comparisons to peers won’t reveal whether that student will one day meet grade-level standards,” the report says. “This risks setting lower expectations for students of color and low-income students, and does not incentivize schools to accelerate learning for historically underserved student groups.”

It’s not clear whether this is true, though.

One research paper compared different accountability systems: a “fixed” approach, where the goal is a set proficiency standard, such as in No Child Left Behind, versus a growth approach based on how individual students improve over time. Using data from North Carolina, the research showed that students generally did better when their schools were held accountable for students’ progress rather than their absolute achievement. Some studies have found that focusing on proficiency incentivizes teachers to pay less attention to students who start far below the standard.

Still, other research has found that No Child Left Behind — which emphasized proficiency — led to meaningful gains in student achievement, particularly in math, and that when labeled as failing, schools generally improve.

Natasha Ushomirsky, director of K-12 policy for Education Trust’s national office, said growth should be measured by looking at whether students are on track to meet proficiency.

“There are ways to measure growth that do measure progress towards a particular expectation,” she said.

Some states have used “growth to proficiency” — meaning whether students who start out behind are improving at a fast enough rate to eventually become proficient.

But this approach has many of the same disadvantages as traditional proficiency models: It doesn’t isolate schools’ performance, and those serving many students who start out further behind will be at an inherent disadvantage.

“As an accountability metric, growth-to-proficiency is a terrible idea for the same reason that achievement-level metrics are a bad idea — it is just about poverty,” said Koedel .

The way schools should be identified as low-performing may depend on what happens to those schools.

“You have to think about how you are using [a given] measure,” said Anne Hyslop, who previously worked at the U.S. Department of Education and is now at Chiefs for Change, a group of district and state school leaders who back choice and accountability policies. “I think the use of any measure in part dictates what level of correlation [with student poverty] we should be worried about.”

Ushomirsky agrees that there shouldn’t be one approach applied to all schools deemed low-performing. “There’s a real opportunity under ESSA to tailor interventions to the needs of a particular school,” she said.

Hyslop argues that there should be different responses based on how much improvement a school’s students are making.

“In the high-growth school, you want to make sure that that school is fully resourced, fully staffed to continue and even expand the great work they are already doing,” she said. “With the school that is both low-growth and low [proficiency], that is where some of the more severe or intense interventions need to occur, because the conditions for catching up may not even be in place yet.”

Hyslop says that states should put most of their energy into intervening in and improving schools whose students have made little progress and are low-achieving.

Research on school closures — the most extreme form of sanction against a school — provides some support for this view. A study in Louisiana found that when low-growth schools in New Orleans were closed and replaced with high-growth schools, student achievement jumped substantially; less discriminate school closures in Baton Rouge actually harmed students.

Opinions vary on how states should design accountability systems under ESSA and how much weight to give to progress versus proficiency. The law requires states to consider proficiency, and it gives them the option to consider growth. Schools also have to use the progress of students learning English and graduation rates for high schools.

States also need to a consider a “fifth indicator” of their choosing, such as chronic absenteeism. The bottom 5 percent of schools must be identified and intervened in each year, but there is significant discretion in what that intervention will look like and how much weight is given to each metric (though academic measures must receive “much greater” consideration than the fifth indicator).

Naturally, there is a range of views on how best to balance the different metrics.

On the issue of growth versus achievement, Hyslop would give equal weight to each, with perhaps a greater emphasis on growth. Koedel says he would first rate all schools based on growth, but then would exempt schools with very high proficiency, his logic being that schools with very high achievement might reasonably focus on areas other than test score improvement.

At least according to their draft plans, many states seem to be more or less following Hyslop’s advice. States including Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, North Dakota, Ohio, and Montana plan to weight student progress equally to or even greater than proficiency.

This means that there would still be some correlation between student poverty and accountability, but less so than in a system that solely relies on absolute performance.

On the other hand, the measures beyond test scores — such as high school graduation and progress of students learning English — are likely to be associated with poverty. Chronic absenteeism, a metric many states are considering, is associated with family income in Massachusetts and Washington state, but not Texas, according to data provided to The 74. States could adjust such measures for poverty, but few, if any, appear to be planning to do so yet.

On top of that, some state plans that prioritize growth in elementary and middle school don’t include it at all in high school, because it is more difficult to measure growth since standardized tests are less frequent.

For better or worse, the highest-poverty schools will likely continue to be at the greatest risk of being labeled failing under ESSA, though perhaps to a smaller extent than under No Child Left Behind.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)