Research Shows Students Can Benefit When a School Closes — but Only If There Are Better Ones to Attend

These findings — from a study released Monday by Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance — may seem obvious, but they’re important, as states have increasingly used school closures and takeovers as a turnaround strategy. In deciding whether to shutter a school, policymakers ought to consider how they’re measuring performance and whether new schools would be any better than those they replace.

The research, conducted by Whitney Bross, Doug Harris and Lihan Liu, examined what happened to elementary and high school students in New Orleans and to high school students in Baton Rouge after their schools were closed or taken over by a charter school. In New Orleans, they examined 11 school closures and 15 charter takeovers; in Baton Rouge, three closures and two takeovers.

New Orleans has been at the heart of controversy after virtually all the city’s public schools became charters. Previous research found that the post–Hurricane Katrina package of changes — including the expansion of charter schools, a stringent system of test-based accountability and an infusion of new resources — led to large increases in test scores. Student mobility also declined, and another recent study found that students in New Orleans charters seemed to do better on measures of behavior.

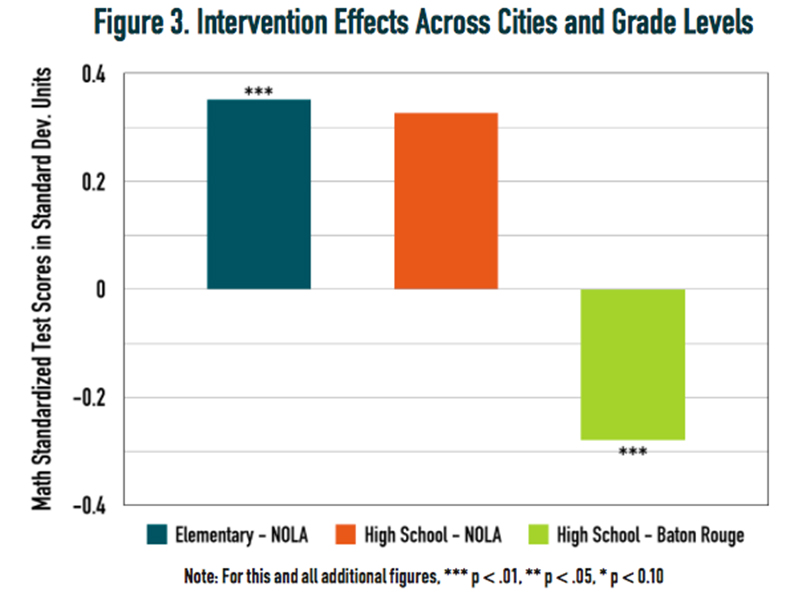

The reforms included closing or replacing schools that were underperforming, as measured by test scores. To assess the impact, the researchers in this study compared students in closed or taken-over schools with students at similar schools that were not eliminated. They found that the strategy seems to have been effective in New Orleans, where students saw large increases in standardized test scores. But in Baton Rouge, the effects were the opposite: High school students were significantly harmed when their schools were shuttered.

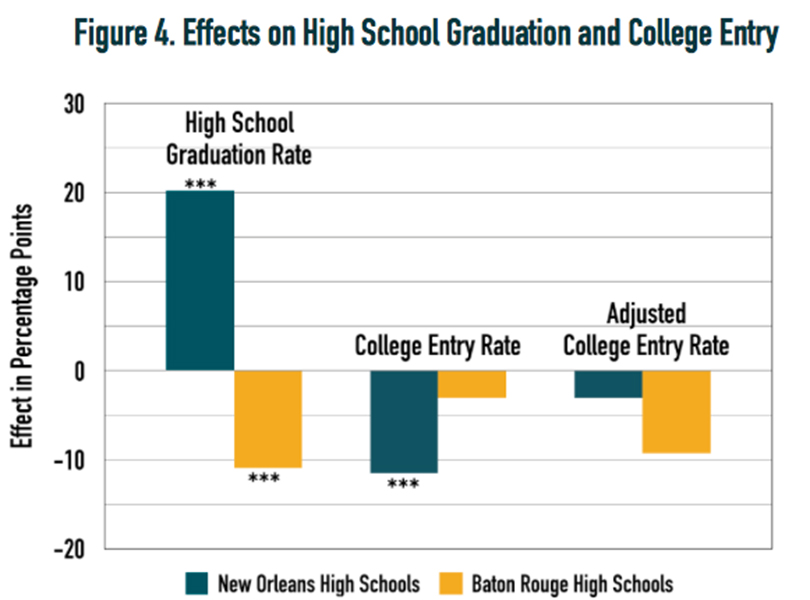

Effects on high school graduation rates mirrored the test score results: New Orleans students from closed or replaced schools were much more likely to complete high school, while Baton Rouge students were less so. In New Orleans, the effects on college entry were close to zero, while in Baton Rouge the impacts were more negative, but not statistically significant.1

The research also found that the effects of closure or takeover tended to be more positive in elementary than high school, and when schools were phased out over time rather than closed immediately.

The study points out that the largest impact from the elimination of struggling schools may fall on future students who otherwise would have attended those schools — since such benefits (or harms) could accrue to multiple generations of students. These future students may stand to benefit in particular because they do not experience disruptive effects of closure, like having to switch schools.

Although they don’t have direct data on this, the authors conducted a simulation based on the closures’ effects on existing students to estimate the impact on theoretical future students. They conservatively estimate that between 25 percent and 40 percent of the test score gains caused by the New Orleans reform package can be attributed to the closure or replacement of low-performing schools.

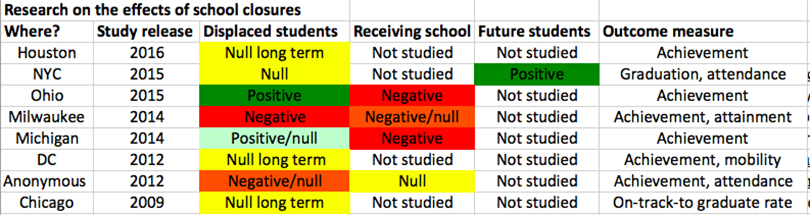

As this study notes, past research on school closures has produced mixed results, particularly on students directly impacted. However, some research has suggested negative effects on students in schools that receive an influx of new students due to closures. Little research exists regarding students who would have attended schools that were closed — but one study did find large, positive results in New York City.

Even less research exists on charter school takeovers. One paper found no impact in Memphis, but another study found big test score gains from takeovers in Boston and New Orleans.

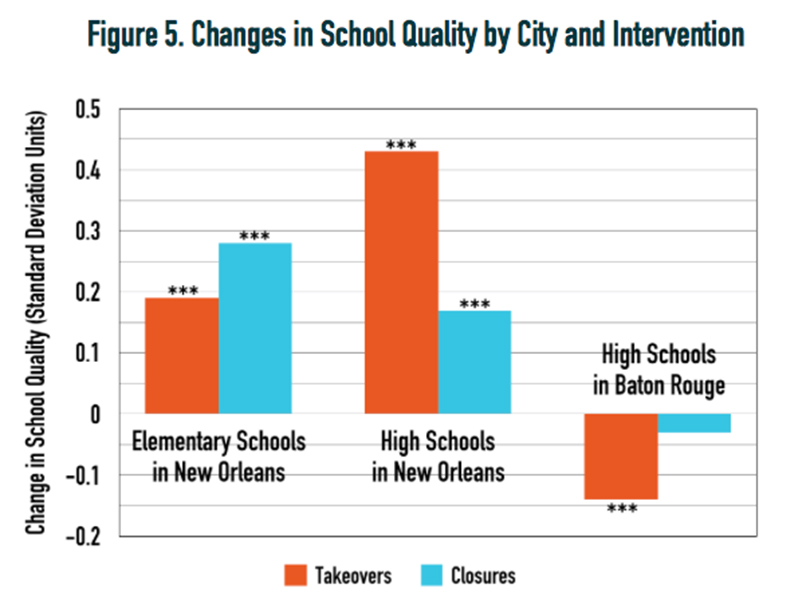

The Tulane report emphasizes the commonsense idea that these sort of interventions work only when new schools are markedly better than the ones closed or taken over. This squares with some previous studies, as well as with the Louisiana data: Replacement schools seemed to be much better in New Orleans, but not in Baton Rouge, and student gains varied based on the effectiveness of the school students moved to.

The report notes, however, that there was “no clear and consistent pattern in how high school graduation and college entry effects relate to school quality improvement.” This suggests, consistent with past research, that measuring schools based solely on test scores doesn’t capture the entirety of their effect on student outcomes.

It’s clear that simply closing a “failing school” is no guarantee that students will benefit. In fact, in places like Baton Rouge and Milwaukee, school closures hurt the kids affected by them, probably due to a combination of the instability created by closures and the quality of the students’ new schools.

Policymakers considering closing schools should proceed with caution, unless there’s good reason to believe that students will end up at a more effective school. For instance, Michigan is considering large-scale closure of schools with low test scores, but Secretary of Education John King said in an interview with Chalkbeat Detroit, “The key question is: What are they being replaced with? What are the opportunities that will be available to students instead?”

The results also point to the importance of measuring school quality appropriately. In judging schools, some focus on raw proficiency rates, but most researchers recommend evaluating schools by students’ test score growth, since schools don’t control the starting point at which students come in. Focusing exclusively on test scores also excludes other important areas of performance.

Closing schools based on bad or limited data is unlikely to be effective and may be harmful.

On its own, research can’t answer whether school closures are a good idea.

The New Orleans data suggest that, at least in some circumstances, closures and takeovers can have significant positive effects on student outcomes, including test scores and high school graduation rates.

But this does not assess the broader impact of this strategy. Some argue that closing traditional public schools has negative effects on communities. In Chicago, for instance, the majority of schools closed by the city remain empty, becoming eyesores and magnets for crime. In New Orleans, the expansion of charters and closure of neighborhood schools led to a large decrease in the number of black teachers and bred significant community resentment.

Others have argued that closures are undemocratic, conducted in some places not by locally elected school boards but by state-appointed leaders. Indeed, in New Orleans, but not in Baton Rouge, the schools were largely under state control (though most were recently returned to community oversight).

Of course, the expansion of charter schools and replacement of less effective schools may also have certain benefits to local communities.

These potential costs and benefits may be real — even if they can’t be captured by research studies.

1. The researchers distinguish between raw and adjusted college entry rates, with the latter accounting for changes in high school graduation rates, since an increase in high school graduates might reduce college entry. As the authors explain, additional high school graduates may be “less likely to go to college than those who would have graduated anyway, [which] would artificially reduce the interventions’ estimated effect on college entry.” Because of that, the adjusted college entry rate likely provides a “more realistic assessment of the college effect, because students who barely graduate from high school go to college at much lower rates than those who graduate more easily and without the help of school interventions.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)