Connecticut’s Critical Deadline: Judge Says State Must Fix Public Education in Six Months

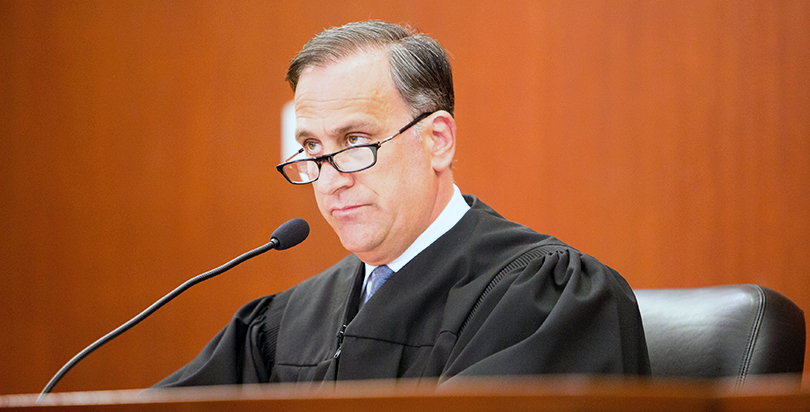

Judge Thomas Moukawsher’s ruling, which he read aloud from the bench over the course of nearly three hours Wednesday, faulted how state funds are distributed, how primary and secondary education is defined, how teachers are evaluated and compensated, and how special education is funded and implemented.

The decision amounted to a broad and often scathing indictment of education policies in one of the country’s wealthiest states while leaving unanswered whether officials there have the means, the time and the political will to uphold it.

“The judge’s decision touched almost the entire landscape of Connecticut’s public education system,” Jim Finley, principal consultant for the plaintiffs, the Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding, told The 74.

“This is a landmark victory for Connecticut’s public school students,” CCJEF President Herbert C. Rosenthal said in a statement.

The decision came in response to a long-running case, filed more than a decade ago by CCJEF, a partnership of local governments, school boards, teachers unions, and education advocates, against Connecticut’s former governor, M. Jodi Rell. It argued that the state’s funding system was inadequate and inequitable.

Moukawsher found fault in the state’s school funding approach — and then went much further in taking apart its public education system.

The sweep of his ruling surprised even the plaintiffs.

“We didn’t anticipate that [the judge] would take on the teacher evaluation system,” Finley said.

(In his own words: read the striking language in Judge Moukawsher’s milestone ruling)

Moukawsher — a former state lawmaker, appointed by Democratic Governor Dannel Malloy — said that although there was enough money spent on schools overall, the way it was distributed was not “rational,” since Connecticut has been without a school funding formula for the past several years. He also chided the state for recent education cuts that he found favored affluent districts over poor ones.

“Too little money is chasing too many needs,” he wrote in his 90-page ruling.

Joe Ganim, mayor of Bridgeport, one of Connecticut’s most disadvantaged cities, called the decision a “huge game changer,” according to the Hartford Courant.

“I think it compels action,” he added. “I think it deserves deference by the state attorney general to abide by this and not appeal it, and the general assembly to act quickly.”

Several other groups — including the ACLU of Connecticut, the Connecticut School Finance Project, the Connecticut Council for Education Reform and Students Matter — also hailed the ruling.

But the state teachers unions, part of the plaintiffs’ alliance, were more tepid.

“Unfortunately, the court declined to provide any remedy for the disparity in resources and revenue for students in the state’s poorest communities — the essence and heart of the CCJEF litigation,” said Sheila Cohen, president of the Connecticut Education Association, in a statement.

State officials declined to comment, saying they were reviewing the decision with their client agencies, a spokesperson for the state attorney general’s office said, according to the Courant.

“We welcome the conversation this decision brings,” Gov. Malloy said, according to The Connecticut Mirror. “We know that to improve outcomes for all Connecticut students and to close persistent achievement gaps, we need to challenge the status quo and take bold action. Since I took office, the state has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in education, with an overwhelming share directed at supporting our students who need it the most.”

While the case largely focused on funding, for Moukawsher that was just the starting point. He also said the way the state defined a secondary education — and how it distributed high school diplomas — needed to be changed, pointing out the large disconnect between the number of students graduating high school and the number ready for college. It was not entirely clear how the state would address this issue, but the judge suggested a system of high school exit exams, similar to those used in several other states, including Massachusetts.

“Judge Moukawsher’s ruling reinforces our position that money alone will not improve our public schools. We are pleased that he has called on our state leaders to make bold changes needed to ensure that students are graduating high school ready for college and career,” Jennifer Alexander, of the reform group ConnCAN, said in a statement.

(The 74: Remedial Courses Come With Steep Price Tag — and Low-Income Students Aren’t the Only Ones Footing the Bill)

Moukawsher also ruled that the state had failed to define the terms of an adequate elementary education, though he said there were “many possibilities” for doing so. He suggested instituting “high-quality preschool” or stopping struggling eighth-graders from moving on to high school.

The judge then turned his ire to the state’s teacher evaluation system, which he described as “useless,” “dysfunctional” and ultimately unconstitutional because it gave the vast majority (98 percent) of teachers high marks and was insufficiently connected to student achievement.

“The state’s teacher evaluation system is little more than cotton candy in a rainstorm,” Moukawsher said.

Connecticut is not alone in evaluating almost all its teachers as highly effective — 95 percent of teachers in neighboring New York were also judged effective or better — and the issue of how to craft an evaluation method more aligned to student performance has been contentious across the country.

(The 74: The War Over Evaluating Teachers—Where It Went Right and How It Went Wrong)

While acknowledging the limits of using tests to grade teachers, the judge chided a state committee for gutting its role in teacher evaluation. “Although it faced a federal mandate to include a connection between teacher evaluation and student learning, [the committee] did everything it could to weaken this requirement and then reconvened a year later to weaken it some more,” the decision stated.

Meanwhile, the state’s system for setting teacher salaries — based, like many others, almost exclusively on years of experience and degrees earned — also failed to meet constitutional muster, according to the judge. Moukawsher pointed to expert testimony claiming a limited connection between those factors and effectiveness in the classroom.

“The billions that flow to increased teacher pay in this state have nothing to do with either how much teachers are needed or some recognized measure of how well they teach,” Moukawsher wrote.

Although the unions were part of the coalition that brought the lawsuit, the ruling marks a major setback for them after a string of recent court victories, including in California, where a successful challenge to tenure and other teacher protections was overturned on appeal last month, and at the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to overturn mandatory union dues earlier this year.

By calling for more stringent evaluation and connecting pay more clearly to performance, the Connecticut decision highlighted several policies that unions have generally opposed.

“The court’s attempt to impose one-size-fits-all mandates that erode flexibility and local education control penalizes the majority of Connecticut’s schools,” said Cohen, of the Connecticut Education Association.

The Connecticut AFT affiliate was even more critical, saying that “we intend to fully evaluate the judge’s comments regarding accountability, which were not just disappointing, but disrespectful of education professionals.”

Finally, the judge turned to the state’s special-education system. First, he said that too much money was spent on students with such severe disabilities that they were unlikely to benefit from it — to the detriment of other spending priorities.

“Neither federal law nor educational logic says that schools have to spend fruitlessly on some at the expense of others in need,” Moukawsher said, in what may be among the most controversial parts of the decision.

Second, the judge argued that the system for defining special needs was “mostly arbitrary and depen[dent] not on rational criteria but on where children live and what pressures the system faces in their name.”

Moukawsher’s decision requires the state to overhaul how special-education funding is spent and to better ensure that the system is not identifying too many — or too few — students as needing special-education services.

In closing, the judge acknowledged the massive implications of his decision.

“Nothing here was done lightly or blindly,” he said. “The court knows what its ruling means for many deeply ingrained practices, but it also has a marrow-deep understanding that if they are to succeed where they are most strained, schools have to be about teaching children and nothing else.”

Bruce Baker, a Rutgers professor who testified on behalf of the plaintiffs, said an appeal and extension were likely: “I can’t even imagine the next 180 days … of redrafting in minute detail pretty much every aspect of Connecticut education policy.”

The ramifications appeared large but were not immediately clear, as many of the judge’s decrees may be challenging for Connecticut to uphold.

On funding, the state is facing a fiscal crisis, and decisions about how to allocate resources are politically fraught even in the best fiscal times. State legislatures, like those in Washington and Kansas recently, often drag their feet before complying with court mandates on school funding — though research finds that when more money is added to the system, student achievement improves.

Meanwhile, the judge’s push to connect high school graduation to college and career readiness has not been successfully implemented in any state in the country, as The 74 previously reported. Doing so would lead to dramatic drops in graduation rates, and other states have inevitably watered down or delayed putting in place tougher requirements. Equity advocates may also be concerned with such an approach since research on high school exit exams has found few benefits but significant negative effects on low-income students of color, who are more likely to be denied a diploma.

States have similarly struggled to implement new teacher evaluation systems that identify a sizable number of teachers as less than effective. Although the Obama administration premised its Race to the Top program on overhauling evaluation to better differentiate teacher quality, many states that changed their system, including Connecticut, continued to award the vast majority of teachers high marks.

The changes required for elementary school and special education were notable for being ambitious but often quite vague.

“He’s got a really long list,” Baker said. “There should have been priorities.”

Connecticut has 180 days — six months — to present its proposed remedies to the many constitutional deficiencies identified by the court. CCJEF will then have 60 days to respond, and the judge will ultimately determine whether the state’s plan is sufficient.

CCJEF’s Finley said the group will likely focus on revamping and fully funding the state’s education formula and improving the special-education system. He said he expects the state’s proposal to include additional spending as well as other policy changes.

“This case was never just about more money,” he said. “It was about showing the unequal impacts of the education system on our high-poverty districts.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)