Connecticut One of 20 States Leading the Charge on Creating Open Education Resources That Stretch From K-12 to College

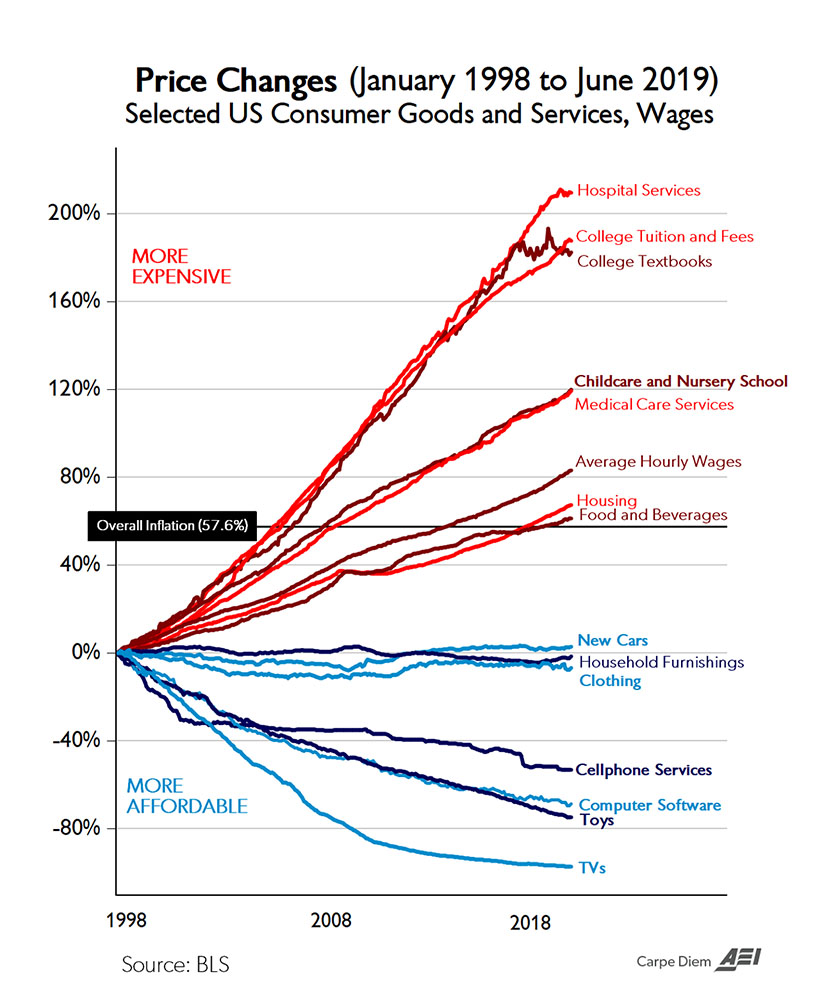

It’s been a dual track. As states across the country look for ways to provide more high-quality resources to classroom teachers, universities have been experimenting with materials that reduce the crushing cost of college textbooks.

In Connecticut, one state commission is looking to unite the two and share open educational resources at all levels, from local school districts through state universities and colleges.

“The idea is that we would have one big repository or index of materials from K-12 and higher ed,” said Doug Casey, executive director of the Connecticut Commission for Educational Technology. “In speaking with some of the folks in secondary education and higher ed, they are excited about that.”

Casey, the state’s cheerleader for equity of access, foresees a future in which professors of community college remedial classes can easily find high school materials that are aligned with state standards to quickly bring their students up to speed. Conversely, high schools would be able to offer classes normally found only at the college level without breaking their budgets.

“There are a lot of benefits we haven’t even imagined yet,” he said.

Connecticut is one of 20 states that are working together to develop best practices and share materials that are aligned with common standards, Casey said. The GoOpen Network plans to develop a technology platform for sharing curriculum materials across district and state lines.

The first order of business is to get the word out.

“We’ve started an awareness campaign, how to get going with OER,” Casey said.

He worked with University of Connecticut students to set up the GoOpenCT website, which provides resources for educators, and created a YouTube channel with testimonials from teachers, administrators, professors and students who have seen the benefits of using shared educational resources.

“I really liked having open textbooks in my class,” says Kharl Reynado, a student at the University of Connecticut. “It really leveled the playing field because all of us had access to the same resources at the same time. It was really affordable, and if we had to print anything out, that was really affordable as well.”

It turns out that telling college students in advance which classes use open educational resources instead of traditional textbooks not only saves students money but also leads to more success, said Eileen Rhodes, director of library services at Capital Community College in Hartford.

“We started labelling courses in spring 2018,” she said. “When a student logs in to register for their courses, they can see #NoLo, which means ‘no cost or low cost.’ Those courses are $40 or less for materials.”

So far, eight of Connecticut’s 12 community colleges use the #NoLo system.

“Here at Capital, we’ve had two 100-level courses in which we switched from a traditional textbook with a cost of about $150 to OpenStax, which is a line of OER that comes out of Rice University,” Rhodes said. “You can download the book for free online or you can print the bound book for about $35. We’ve seen an increase in the number of students who have passed the course and a decrease in the number of students who dropped out of the course.”

Capital is just beginning to track the data for remedial classes that have made the #NoLo switch, Rhodes said. Having data is important when trying to convince professors to change their ways.

“There are two camps,” Rhodes said. “Some professors are all in. But a lot of professors feel that if you are paying more, there is going to be a higher quality attached to it. I think a lot of professors, though, I hate to say it, but they want to just do things the way they’ve always done them. The publishers calling them up and saying, ‘We have your textbook, we have all your ancillaries, your PowerPoints, your test banks, all you need to do is just choose us and you’re good to go.’”

Adjusting to change is rarely easy. Abbe Waldron, instructional leader for technology in Connecticut’s Region 14 school district in Woodbury, has created a digital literacy curriculum that is aligned with state and national standards as well as American Library Association standards.

She identified the topics that were critical for students at each grade level in the district of almost 1,800 students, and she is putting together an implementation guide with assessments and resources that will be shared statewide.

“So many people are doing the same work in isolation, but it would be really great to work together, to work with people in other districts,” Waldron said. “People are really generous with their work.”

Region 14’s curriculum budget for some content areas has been cut by two-thirds since using open educational resources, Michael Rafferty, the district’s director of teaching and learning, said in his GoOpen video.

In many cases, it’s a matter of tapping into what’s already there, Casey said.

“Directors of curriculum do all that work and develop all these unit plans and lesson plans, and they’ve got to be stored somewhere,” he said. “So, you’ve got that process times 169 towns, so you step back from that and say, ‘Wait a minute, if we are all designing these materials based on the standards, somewhere out there probably stored in the cloud and stored in the Google Drive — because every single district uses Google for storage — there are some great lesson plans out there.’

“If you could somehow open that all up and connect it, you would have a phenomenal statewide collection of lesson plans that are all aligned with state standards.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)