Closing San Antonio’s Digital Divide: In the City’s Poorest and Most Segregated Neighborhoods, Public School Students to Get In-Home Internet

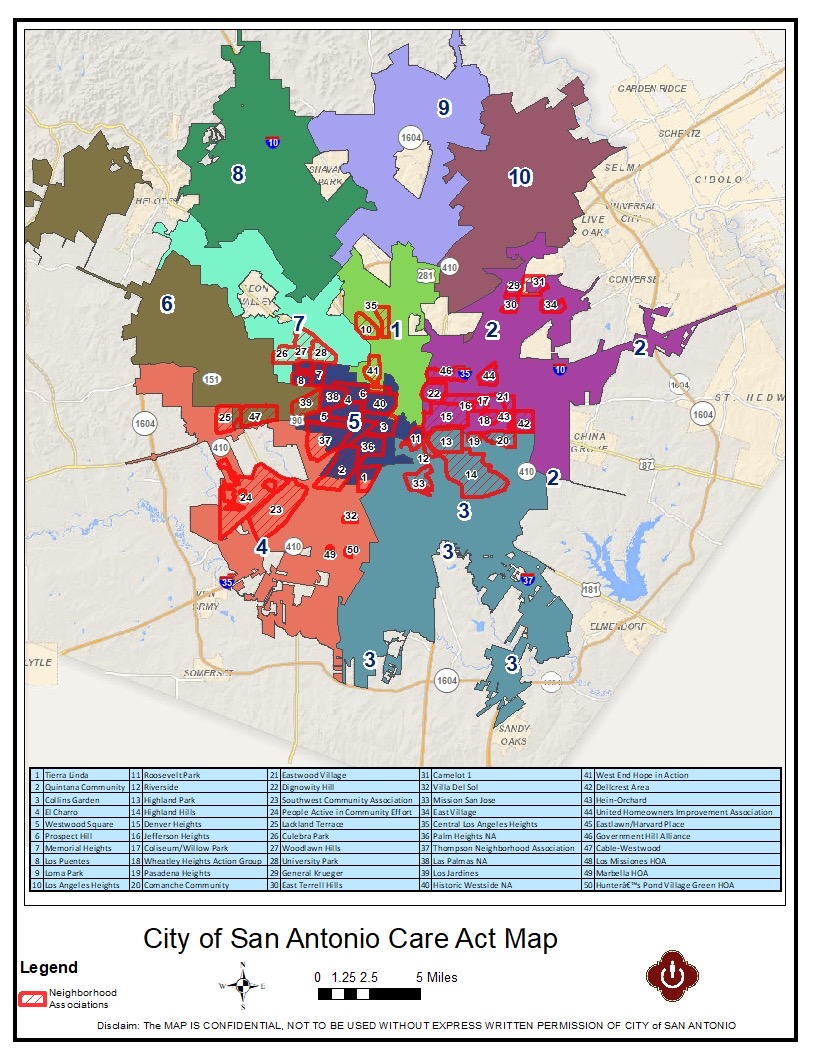

San Antonio is closing the digital divide for students in 50 of the city’s low income neighborhoods — and it took a pandemic to make it happen.

In a solution jump-started by COVID-19 and the federal relief funds it triggered, a new $27 million program will enable students to access their school’s broadband network from home.

The initiative, headed by the City’s Office of Innovation and a cadre of public and private partners, will launch in the fall in the six neighborhoods around Lanier High School.

“It’s all of our responsibility to close the digital divide,” said City of San Antonio Chief Innovation Officer Brian Dillard, whose department led the coalition of public and private partners.

The rapid school closures earlier this year sent school districts across the country scrambling to connect students to online lessons. Now, plans to close the digital divide in cities like San Antonio and Cleveland are an effort to avoid a repeat of the problems created by the lack of internet access when the pandemic began.

When the pandemic closed schools in March, 75 percent of the students at Lanier were connected to their teachers via an unsustainable patchwork of donated hotspots and strategically parked buses emanating Wi-Fi.

The school sits in what one local advocate called “the Bermuda triangle of internet connectivity” in San Antonio. Families living near Lanier who can afford broadband still cannot get it because of a regulatory stalemate between public institutions and private telecommunications companies.

Internet service providers have not placed the necessary infrastructure in the low-income neighborhood. Cities and schools are prohibited by law from creating competitors with the private networks by offering their own services.

The impasse has left the Lanier area and other neighborhoods on the wrong side of the digital divide — until now.

As in many cities, San Antonio’s digital access falls sharply along economic and, often, racial lines. American Community Survey data show that 79.6 percent of San Antonio’s Black households have computer and broadband internet, compared with 89.4 percent of Latino households and 91.3 percent of white households citywide.

Access, and lack of access, is concentrated in certain areas.

A report from the nonprofit SA2020 examined the digital divide across the city’s ten council districts. In the district with the highest concentration of white families, the per capita income is more than $42,500 and 90 percent of homes have access to broadband.

In Lanier’s city council district, which has the lowest concentration of white families, per capita income is less than $14,000 and 54.6 percent of homes have broadband access.

This fall, when students enroll at Lanier or nearby middle and elementary schools, they will be given the equipment to access SAISD’s local network while in their homes. The pilot will overlap with a couple of neighborhoods in Edgewood Independent School District, allowing those students to access Edgewood’s network.

The Lanier pilot will look similar to a successful program launched three years ago by the tiny Castleberry Independent School District in North Texas, where 82 percent of the 3,700 students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch and rural broadband infrastructure was minimal at best. The district was able to construct towers high enough to broadcast its own content-filtered network into homes. So far, it’s reached 93 percent of Castleberry students.

“We didn’t see COVID coming, but we did see the need for digital equity,” said Castleberry director of technology operations Jacob Bowser.

As the pandemic worsened earlier this year and schools shuttered, the program’s value was amplified. “We were ready, pretty much [from] day one,” Bowser said. “If I was going to say ‘I told you so’ to anyone, I would probably start there.”

In Castleberry ISD, about 66 percent of the district didn’t have sufficient internet to do homework at home. Teachers were the cheerleaders for the initiative, he said, because they wanted their students to be able to do more project-based learning and research-intensive homework.

COVID-19 has proved a point Lanier High School Principal Moises Ortiz has been trying to make for years: The homework gap is debilitating, hazardous, and unethical.

If his students wanted to do research for projects or get help on homework after schools and public libraries closed, he said, they had to find a parking lot or a late-night restaurant that would let them sit for hours without ordering refills.

“They were going anywhere and everywhere just to connect,” Ortiz said. It was burdensome and, frankly, unsafe. He’s certainly not glad for the pandemic, but, like many, he says he’s glad to see more urgency given to what has always been an urgent issue at Lanier.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)