Charters and District Schools Share Strategies on Getting Low-Income Students Through College, Putting Uneasiness Aside

This is an excerpt from the new Richard Whitmire book The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. See more excerpts, profiles, commentaries, videos and additional data behind the book at The74Million.org/Breakthrough.

In June 2015, when Pedro Martinez was appointed superintendent of San Antonio Independent School District, everyone in this city assumed he was a good hire. But few realized just how radical that hire would prove to be. Martinez looked around his new district and didn’t like what he saw. The students looked just like him, and they were struggling. Martinez’s family emigrated from Mexico when he was 5, and he grew up poor in Chicago. He was the first in his family to go to college. What worked for him, going to college, wasn’t happening often enough in his new district.

“One of the things I noticed very quickly was the low numbers of students entering colleges, specifically universities. Less than half of our students were attending any type of college after high school, and less than half of those were attending universities,” he said. “Most concerning was a mismatch for some of our top kids. I saw our top kids attending community colleges and lower-tier universities.” Only about 2 percent of students at the San Antonio district ended up in top-tier colleges or universities.

For years, school leaders in San Antonio had essentially settled, accepting their fate as a high-poverty, low-performing district. Martinez, however, was determined not to settle and set off down an ambitious path to build a “system of great schools” by opening up new, higher-performing school options for parents. That he wasn’t afraid to step on toes became clear when he sought out Democracy Prep, a high-performing charter network from the East Coast, to take over a struggling elementary school. Almost immediately, San Antonio rose to the top ranks of innovative districts, joining Indianapolis and Denver.

All the reform moves launched by Martinez boiled down to a single goal: We need more of our students going to colleges, especially top colleges. That caught the eye of Mark Larson, who oversees the KIPP charter schools in San Antonio. As Larson acknowledges, charter schools, including his own at KIPP, don’t get everything right. But KIPP has long been a pioneer in boosting college success rates for its low-income, minority graduates. They had this one thing down pat, and they wanted to share. By themselves, they were reaching too few students. Martinez, who seemed open to charters and ran a roughly 50,000-student district, made an ideal collaborator.

Today, neither Martinez nor Larson can recall which of them reached out first, but those meetings happened, mostly at breakfast and lunch. “Part of it was helping him navigate the who’s who in San Antonio,” said Larson. “I wanted him to be successful.” Soon, however, the discussion broadened, and they looked for ways to work together. “We both dream pretty big.” The obvious collaboration was college success — it’s what Martinez wanted the most for his students and it’s the expertise Larson had to share.

“After two minutes they came back and said, ‘We’re in. We believe in this. Let’s go.’”

—Mark Larson, KIPP charter schools San Antonio

Larson took the first step, offering to explore expanding a college success grant KIPP had been promised by Valero Energy Corporation’s foundation to include a pilot charter/district collaboration. Larson made his pitch when Valero foundation officials came to visit KIPP. After a school tour, Larson proposed a dramatic change to the promised gift. “I said, ‘Hey guys, remember how I asked you for $300,000? I would like to change my ask to $3 million over five years, and let me tell you why.’”

The “why” was this: Larson proposed using a large portion of the grant to run a pilot college success collaboration with Martinez’s district. The money would cover the planning work, hiring a full-time KIPP counselor to work in a San Antonio high school, training existing counselors and more. After listening to the pitch, the Valero staff asked to discuss it privately in the hallway. “After two minutes they came back and said, ‘We’re in. We believe in this. Let’s go.’”

What happened next was a surge of collaboration between KIPP college counselors and San Antonio ISD counselors. To avoid triggering any backlash from district teachers, Larson made sure all the materials got stripped of any KIPP logos. “We wanted our tools to get into the hands of as many students as possible, and we knew that if it said KIPP, some would view it as suspicious, which would have inhibited its use.” For the first time, some San Antonio ISD counselors got exposed to data-driven college selection advice as KIPP shared its extensive research on which colleges succeed with first-generation students, and which fail them. That nearby community college your students have been flocking to for years? The odds of them actually earning degrees are slim. Some of the district counselors seemed shocked by the numbers.

At Thomas Jefferson High, the pilot school where a KIPP adviser spent most of her time, counselors estimated that 53 percent of their 2017 graduates were accepted into four-year colleges, compared with only 26 percent in 2016. “We’re seeing a marked increase in the number of students who not only are graduating and going to college, but are being accepted to tier-one universities,” Martinez said of the pilot. The experiment worked so well, in fact, that in November of 2017, Valero gave San Antonio $8.4 million, a five-year grant that pays for two new college advisers at all seven of the district’s comprehensive high schools. Also part of the funding: The district is able to triple the number of students it can send on college tours. And perhaps the less-noticed but possibly most critical part of the gift: The district was able to establish an office that tracks its alumni through college, a rarity for any school system, especially a high-poverty urban one.

The goal by the year 2020 is that 80 percent of San Antonio ISD’s graduates will attend college, with half going to four-year colleges and 10 percent enrolling in a tier-one university.

‘People like you don’t graduate from Texas A&M’

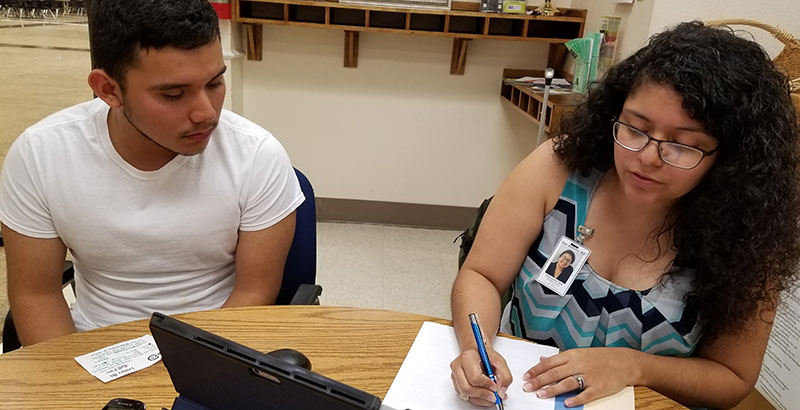

Lanier High School is San Antonio ISD’s highest-poverty high school, where in the past, few graduates made it to prestige colleges. On this day, newly hired counselor Kassandra Peña is meeting with Edwin Gonzalez, a senior headed off to Texas A&M. At Lanier, Gonzalez’s admission is considered a coup. But his journey will be precarious as he juggles multiple grants and scholarships.

For Gonzalez, life as a balancing act is nothing new. His parents divorced when he was young; he has never known his father. Gonzalez, who was born in San Antonio, and his two older siblings were raised by their mother, who has a residency permit and works as a cook and dishwasher in a Mexican restaurant. His only shot at going to Texas A&M is with a full ride, which Peña patched together for him. Now she has to make sure he walks that tightrope to hang on to those grants and scholarships.

“In order to keep those grants, you have to submit your FAFSA [Free Application for Federal Student Aid] every year,” she reminded him. “You signed up for Project Stay, right?” Gonzalez nods yes. “That’s awesome,” said Peña, explaining that Project Stay helps students keep on top of their different sources of financial aid. Each has its own renewal deadline, its own academic requirements, and its own rules for the minimum number of course hours that must be taken every semester. Some have community service requirements.

In Peña, Gonzalez has expert — and very personal — guidance. She grew up in similar circumstances and also went to Texas A&M, where she had to juggle various grants. Peña also knows what it’s like to face overwhelming coursework challenges. She is originally from Chicago, but her family moved to Houston when she started high school. “When we moved, my parents divorced, and it was really tough on my mom because my father had been the sole breadwinner of the family. So my mother started working three minimum-wage jobs to put food on the table for four kids. The only time I even saw my mom was when she was getting ready for work. Then I’d see her asleep on the couch after working a third shift. When I was growing up, I always remember my mom pushing education because when she was younger, she loved school, but her mother forced her to drop out to harvest fruits in the Rio Grande Valley. Peña’s own father, she said, was very traditional. He would tell her: ‘You’re going to cook, you’re going to clean. You’re going to learn how to do all those duties.’” Her mother, by contrast, was always trying to pull her away from those chores so she could do schoolwork. “I remember my parents fighting about it, with my mom saying, ‘She’s going to do her homework.’” For a birthday present one year, her mother gave her multiplication flash cards.

Her mom’s academics-first stance won the day. Peña got a full-ride scholarship to Texas A&M. “My mom really pushed me to pursue a medical degree or become a dentist, so I decided to major in chemistry, even though I didn’t do well in chemistry or math in high school.” College turned out to be a shocker. She failed both chemistry and calculus.

And when she told her adviser she wanted to switch majors to English — writing was her strong point — her academic adviser said she’d be better off just dropping out. The words that will forever burn in her memory: “People like you don’t graduate from Texas A&M.”

But Peña believed in herself and registered as an English major without the help of the adviser. Soon, she had a friendlier adviser and got a 3.8 grade point average for the semester. After earning her diploma from A&M, she worked as a college adviser for two years with Advise Texas, a chapter of the College Advising Corps, and then got hired by San Antonio ISD as part of the Valero grant. Her background seems like a perfect fit for Lanier. All the students here remind her of herself. “My goal as a college adviser is to help students not only get accepted into college, but get accepted into a college with significant financial aid so the money burden isn’t such a big factor.”

Peña also gets something that a counselor coming from a middle-class background might not instinctively understand: Only rarely are students from high schools such as Lanier going to post the kind of college admittance test scores assumed to be needed to qualify for top universities. Gonzalez, for example, has a relatively low SAT score, and his track record with Advanced Placement coursework is not great. But that’s no reason to steer students like Gonzalez away from applying to universities such as Texas A&M, places that have what she describes as “holistic” admissions, whereby college admissions officers look beyond just test scores. “They want our kids from San Antonio.”

KIPP’s tips to San Antonio’s college counselors

At a gathering of the district counselors at the Cooper Learning Center, the leadoff speaker is Eduardo Sesatty from the KIPP Through College program. Everyone here knows him as “Lalo,” and he’s the primary liaison between the district and KIPP for ongoing collaboration efforts. He seems pretty well accepted. Everyone in the room appears to know he just got back from his honeymoon. At this point, there’s only a light-touch relationship between the district and KIPP. Sesatty’s role in this gathering is to offer “KIPP tips” — practical advice that the district counselors might find valuable. Today, Sesatty has three to pass along, supported by slides.

Tip 1: Sesatty told the counselors that as everyone already knows, there was a major glitch this year with the all-important FAFSA program. In high-poverty school districts, the FAFSA is a dealmaker/dealbreaker process. Without aid, these families, whether from KIPP or San Antonio ISD, couldn’t even consider college. In a normal year, maybe a fifth of the students would get selected to endure “verification,” a time-consuming process in which the federal government demands extra paperwork — lots of it — to prove the family financial data is accurate. In 2018, however, due to an apparent computer glitch, Sesatty said, about 80 percent of the students got verification notices, a development that was proving to be nightmarish. Parents couldn’t understand why they were being asked to provide sensitive financial information from the IRS, which delayed the verification process, which delayed financial award decisions, which, in turn, delayed the college selection process.

It was turning into a disaster. Here’s how KIPP is dealing with it, Sesatty said. The students themselves can request the material from the IRS, he explained; all the students need is their parents’ Social Security numbers, birth dates, and home address. So KIPP wrote a “script” of exactly what the students should say. “We would pull the students out of class, put them in a room, have them call their parents and read from the script.”

Tip 2: The district, Sesatty said, should consider ramping up its college signing day ceremony, which at KIPP San Antonio is known as the College Commitment Ceremony. At KIPP, he said, this is a bigger deal than high school graduation day. “All 3,000 students from KIPP attend,” Sesatty told them. “The seniors declare where they will be graduating from college, and they do it in front of all the students. They go up to the microphone and announce: ‘I will graduate from Brown University!’ By saying when they will graduate from college is embedding the idea that this is just the next step. It’s not done. They’re making a promise to their peers that they will finish this thing.

It’s like a glorified pep rally. I call these thing celebratory rituals. You’re celebrating that they applied to college, celebrating that they got accepted, and celebrating that they decided where they are going. I showed them a YouTube video from one of our commitment ceremonies from a few years ago.”

Currently, college signings in San Antonio are a citywide event, where students from multiple districts come together. Once there, they gather in groups — everyone going to the University of Texas at San Antonio sits in one section of the stadium. There are no personal declarations, however, no promises to graduate made in front of peers. The district counselors saw the difference, Sesatty said, and wanted to shift to a more purposeful celebration.

Tip 3: For the first time this year, Sesatty said, KIPP came up with a new software tool called a college award analyzer. Once students receive offers from different colleges, they can enter their financial data: tuition, room and board, and also the awards and grants offered to help their families pay for college. “The tool will calculate a return on investment based on the cost of the college, the college’s graduation rate, and the potential salary based on what they are choosing for a career. It’s a way of seeing college not as cost, but as an investment. Sometimes families may see college and the cost of college as a threat because they don’t understand the potential benefits in the long run.”

The tool also helps the counselors make the case that choosing a more expensive option often can pay off over the long term. “We can visualize to students and parents which are the better options. Community college may be cheap, but that doesn’t always mean that’s the best choice.”

Antagonism gets in the way … but not entirely

So can these collaborations spread? At first, the answer appeared to be unlikely. The KIPP/San Antonio compact started in 2015, proved itself by 2016, and in 2017, the program blossomed with the $8.4 million gift from Valero. That early success, and the injection of outside money, should have looked like catnip to other superintendents: Martinez gets 18 new college counselors for his high schools completely paid for by a foundation, free college advising advice from KIPP, and he gets to watch a rising college success rate for his graduates — all without losing a single student to a charter and getting no resistance from the teachers union. Hard to cast this as anything other than a win-win. So I was taken aback when I asked Martinez how many superintendents had stopped by to see how it all worked so they could duplicate it in their districts. His answer: None.

Why? “I’ve been doing this work for a long time, and I feel like right now we’re at a point where you have this partisan sort of polarized situation where people feel like it’s either traditional public schools or charters. If you chose one or the other, the other is the enemy.” For most district superintendents, working with a charter amounts to treason, Martinez said. “For me, I see things differently. There are some charter operators that I really admire. At KIPP, I like their dedication to following these children all the way through college, with a college diploma being the goal. At Uncommon Schools in New York, I love the way they measure their success — that these high-poverty children of color can be at the same level as affluent white children.”

The issue for district superintendents in places such as San Antonio, he said, is figuring out how to take to scale what the best charters have done with far smaller numbers and with a lot of help from philanthropies. While an $8.4 million grant from Valero was both generous and helpful, that’s small compared to what Valero has done with KIPP San Antonio. If the grant were matched on a per-pupil basis, his district would have received $75 million.

Mark Larson at KIPP agrees with Martinez about the charter/district antagonism being a big player in districts avoiding even a win-win program such as the college success collaboration here. But there’s another factor, as well, he said. “In education, great ideas don’t travel well. We don’t like to acknowledge that somebody else has a better idea. In industry, great ideas are stolen all the time. You go out and try to figure how out to borrow it, copy it, or pay for it. Whatever. In the education space, we just don’t do that well.”

Only four months after my visit to San Antonio there was a surprise announcement from KIPP: A new college counseling collaborative got funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation that partners the network’s national KIPP Through College team with college advisers from New York City, Miami, Newark, and the Aspire charter network in California. In July 2018, I returned to San Antonio (the city was chosen as the meeting ground because of the groundbreaking collaborative here) to observe the initial meeting at a Riverwalk hotel.

On the first day of the three-day conference, KIPP leaders laid out the basics, making clear that their program arose from humble beginnings. In 2011, KIPP discovered that its college success rate was far less than expected. “We were sending 9 out of 10 of our graduates to college, but only 3 out of 10 were graduating,” said Sarah Gomez from KIPP Through College. “That was shocking to learn. Our reaction: How could this be happening?” Although that rate was still three times better than the national average for similar students, KIPP concluded it had to do better and launched KIPP Through College, an aggressive attempt to inject science into what had always been treated as art.

A quick summary of what KIPP discovered in those early years. KIPPsters were applying to too few colleges, when they should be applying to nine. They were applying to too many colleges that had poor graduation results for low-income students. And they weren’t applying to many “reach” colleges — a problem because selective and highly selective colleges put far more resources into their students, which pushes the graduation rates into the 90-percent range. “Seventy percent of our students were applying to ‘likely’ colleges,” said Gomez, referring to what are popularly known as safety schools.

The “star” graphic from the entire session, shared repeatedly, showed the graduation rates of colleges that ranked from non-competitive (23 percent) to most competitive (85 percent). But the sweet spot of the graphic, emphasized over and over, was that within each category, such as “competitive,” the graduation rates can vary by as much as 20 percentage points. That means picking the right college — let’s say within the “competitive” range — can have the same graduation likelihood effect as getting that student into a “highly competitive” college.

So what are the right colleges and the right mix of applications? KIPP pioneered early software programs to build its College Match program, which guides both students and counselors on the path to finding affordable colleges where they are most likely to earn degrees. One of those early software developers, Matt Niksch, left KIPP for Chicago’s Noble Network of Charter Schools, where he had access to larger pools of network alumni in colleges. The programs he wrote at Noble were then adopted by KIPP and other charter networks.

“‘Wait, I’ve been sending kids to a community college where there’s a 3 percent chance they will earn a four-year degree?’”

—Ruben Rodriguez, KIPP San Antonio college counselor

The fruit of all that research, including access to the software, is what the partnership offered to these traditional schools. Their representatives seemed especially interested in what the speakers from San Antonio ISD had to say. That’s understandable; they were learning about the experiences of a traditional school district, just like theirs, that was in its second year of a collaboration with KIPP. Linda Vargas-Lew, who oversees San Antonio’s new college advisers, described some early payoffs. In just two years, she said, the district doubled the number of graduates headed to selective colleges.

And Vargas-Lew was honest about the reluctance she experienced among some in the district to collaborating with charters. What she heard: “I don’t want to work with charters; they steal our kids.” Also talking to the group was Ruben Rodriguez, the KIPP San Antonio college counselor who had partnered with the district from the beginning. He described the raised eyebrows among the district’s college counselors when they saw the KIPP research about graduation numbers from area colleges, especially the extremely low odds of a student enrolling in one of the several nearby community colleges and then transferring to earn a bachelor’s. “When we showed that slide, the reaction was, ‘Wait, I’ve been sending kids to a community college where there’s a 3 percent chance they will earn a four-year degree?’ We turned it into a social justice issue.”

Sharon Krantz, who oversees counseling for Miami-Dade public schools, said the KIPP Through College collaboration began when the district partnered with the charter network to open an elementary school, KIPP Sunrise Academy, in the high-poverty Liberty City neighborhood. As part of those discussions, the district and KIPP settled on another common interest — introducing KTC experiments in two district high schools in that same neighborhood. Attending the conference were principals and counselors from those high schools. “We want to bring those practices to our district,” said Krantz.

Kelly Williams, who oversees counseling at Newark Public Schools, said their counselors do a good job finding spots in colleges. The problem is keeping their students there. That’s the part of KTC that she wants to adopt: “That work is very successful under KIPP.”

Newark is just beginning to track the college success rates for its graduates, something few districts do. What will they discover? The news may not be encouraging, if a recent Rutgers University study holds up over time. Only 13 percent of Newark graduates end up with either college degrees or professional certificates, according to the study.

Verone Kennedy, who directs charter partnerships for New York City schools, was part of the Empire State delegation there. “My job is to create synergistic relationships between charters and our schools. Our chancellor takes the position that these are all our children; we should not differentiate between the two. How can we be innovative together?”

This is an excerpt from the new Richard Whitmire book The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. See more excerpts, profiles, commentaries, videos and additional data behind the book at The74Million.org/Breakthrough.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation funded a writing fellowship that helped produce The B.A. Breakthrough and provides financial support to The 74. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to KIPP and to The 74. The 74’s CEO, Stephen Cockrell, served as director of external impact for the KIPP Foundation from 2015 to 2019. He played no part in the reporting or editing of this story.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)