‘Families Have to Have a Voice’: Martinez Cites Importance of Parents as Chicago District and Union Agree on Wednesday Student Return

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated

Staff members will return to schools in Chicago Tuesday and classes will resume for all students Wednesday under an agreement between the city and the teachers union announced Monday night.

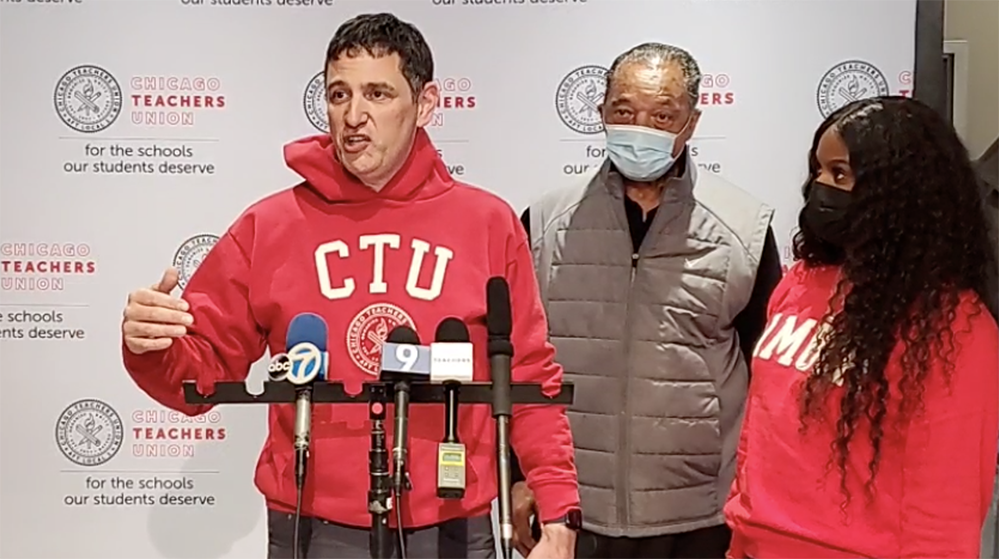

The Chicago Teachers Union’s delegates voted 63 to 37 to approve the agreement, which still has to go to the full membership for a vote. It’s not “a perfect agreement,” CTU President Jesse Sharkey said in a press conference. “We felt like we were asking for reasonable things.”

Meanwhile, Chicago Public Schools CEO Pedro Martinez said in a separate press conference that 16 percent of the staff turned up at schools Monday and three schools were able to provide full instruction. He said one lesson from the work stoppage is the importance of listening to parents.

“Families have to be at the table,” he said. “Families have to have a voice especially as we move forward.”

If Chicago schools had been open Friday, Claiborne Wade’s children would have been there.

A father of four and a parent liaison at DePriest Elementary, Wade serves on the school’s safety committee and feels the staff is doing all it can to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks. Even so, he and his wife faced the same predicament as the rest of the district’s families last week, forced to work from home while their children continue to miss out on learning.

“We’re the fortunate ones, but the parents I serve at DePriest have to go to work,” he said. “There is no bringing work home, and child care is expensive.”

What the Chicago Public Schools calls an illegal strike and the Chicago Teachers Union labels a mere “work action” entered its fourth day Monday, leaving families wondering how long their children would be left without instruction. On Saturday, the union made its latest offer, refusing to back down from its insistence that learning stay remote until the 18th, but offering to have staff members at schools on Monday to distribute internet devices and register students for COVID-19 testing. The district promptly turned that down, saying that the district is “firm that both staff and students should return for in-person teaching and learning as soon as possible.”

Addressing reporters Saturday, union president Jesse Sharkey said his team was “suggesting a way out of the impasse” and accused Mayor Lori Lightfoot of “bullying.”

Omicron has made an already tense relationship between Lightfoot and the union even worse. A 2019 strike over pay, class sizes and staffing demands lasted more than two weeks. By posting the numbers of teachers who reported to schools last week, the city has also drawn attention to division within the union.

On Sunday, a Twitter account posted a statement from Adriana Cervantes, a union field representative at Hubbard High School, who warned that the union had not yet determined “what action will be taken against those who are not participating in the work action.”

The letter warned members not to go into the building Monday.

“If you continue to allow the mayor to divide our membership, soon we won’t have a union to fight for anything,” she wrote.

While some parents have become used to quickly rearranging work schedules and caregiving duties after almost two years of last-minute closures, the standoff is adding to resentment some families already feel toward the mayor and union leaders.

“There’s going to have to be some repairing after this,” said Maureen Hehir, who has three children in the district and teaches special education in neighboring Community Consolidated School District 59. “We’re going to lose people, and it’s so unfortunate.”

Vanessa Chavez, who has a sixth- and seventh-grader in the district, said parents who supported the union during the last strike now feel betrayed.

“I almost feel like we’re caught in the middle of a custody war,” she said, adding that those who advocate for their children’s needs feel they’re being branded as “anti-teacher.”

And Dr. Beth Van Opstal, a parent and physician who treats COVID-19 patients at Chicago’s Rush University Medical Center, said all she hears are extremes.

“Sometimes, I think it’s like all daisies and roses when you hear from the mayor and CPS,” she said, worlds away from the perspective of the union, which she described as relatively unchanged from a year ago before more than 90 percent of teachers were vaccinated. “I don’t know a single pediatrician [who is as] in favor of remote learning as CTU.”

Chavez and Van Opstal were among a small group of parents who met over Zoom Sunday night with Dr. Allison Arwady, who leads the Chicago Department of Public Health and participated in press conferences last week with Lightfoot and district CEO Pedro Martinez. Natasha Dunn, another parent on the call, said she wants to make sure the district’s COVID data is “palatable for parents in the community.”

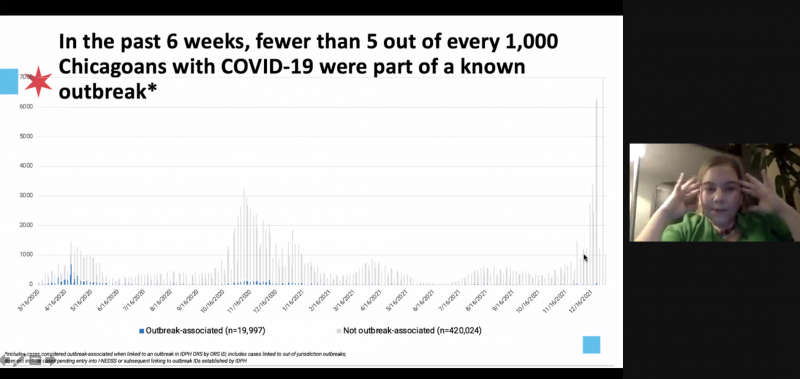

Arwady presented data on outbreaks across the city in both schools and child care centers and reiterated the city’s position that schools are not driving the increase in cases. An outbreak, she said, is usually limited to two or three students. While their classmates or other close contacts are also quarantined, less than 5 percent end up testing positive, she said.

She noted the importance of keeping community institutions like schools open.

“We don’t close hospitals because one wing is understaffed,” she said.

Testing opt-out debate

Parents also asked Arwady about COVID testing protocols, a major area of disagreement in the negotiations. The union wants a screening program in which all schools test 10 percent of students and staff every week, unless parents opt out, as well as a supply of rapid tests to send home if students are showing symptoms. The district said it would work with the union to increase testing options, but that it’s important to get “explicit parental consent for any medical test.”

Lightfoot, meanwhile, tweeted on Saturday that the city would buy 350,000 rapid tests from the state, after Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker offered help.

Cristina Hernandez, whose 4-year-old son Nolen is in pre-K at Darwin Elementary School, doesn’t think the union’s demands are unreasonable. With a child too young to be vaccinated, she thinks testing should be mandatory.

Her family tested over the holidays and her son’s results were positive.

“If we wouldn’t have gotten tested, we would have sent him to school,” Hernandez said. “He didn’t have any symptoms. He’s just had this cough off and on since October.”

She admits, however, that she’s not sure how Nolen would respond to virtual learning. He took a remote music class when he was 3, “and it was just the worst,” Hernandez said. “But it’s not like CTU is saying we’re going to go remote for the rest of the year.”

Pamela Caskey said her two children treated last week “like extra vacation time.” If the district does switch to remote learning, she’s hoping they’ll consider reopening classrooms for students with special needs. Her fourth grader has autism and ADHD and normally has a one-on-one aide in the classroom. During virtual learning, the “aides are on there with the teacher, but they are not able to provide a student individual attention.”

She said she supports “teachers’ rights” and that remote learning makes sense “if they are constantly having to send classes into quarantine.” At her fourth-grader’s school, Hanson Park Elementary, 53 students are currently quarantined, while 21 students are out at Goethe Elementary, the school her second-grader attends. At both schools, the rates are lower than they were in the fall.

The union argues the district’s data is not up to date and points to state health data showing that schools account for almost 43 percent of potential exposure. When parents asked Arwady about that, she noted parents of school-age children are more likely to answer calls from contact tracers than an adult who might have been exposed at a store or restaurant.

Going forward, Caskey said she’d like more comprehensive data on a school-by-school basis. The district’s website includes numbers of positive cases and students in quarantine, but she’d also like to see student vaccination, and even hospitalization rates.

“I don’t know if we’re at the point where we can adjust how we handle when people are getting sick,” she said. “But if everybody keeps getting it, hopefully it will be mild enough to treat it like a cold.”

‘A product of the pandemic’

As a teacher in District 59, northwest of Chicago, Hehir sees a sharp contrast between the issues on the table for Chicago and the way her district handles positive cases. District 59 doesn’t flip entire classrooms to remote learning if there are positive cases.

“All of our buildings are open,” Hehir said.

CTU wants triggers for district-wide remote instruction as well as guidelines for closing individual schools based on staff and student COVID-related absences. The city rejected the district-wide approach, but said the triggers for school closures require more negotiation.

Hehir added that in her district there has been a scramble to keep classes covered when teachers are out sick, but she thinks reducing quarantines to five days will help. Last week, she and her husband took turns staying home with their children. On Monday, the grandparents were taking over.

She’s most concerned about her first-grader Emmet, a “product of the pandemic,” who gives her a hard time about going to school and tells her he has no idea what he’s supposed to be doing in class.

“My kids are still mad at me because I did print things out for them to work on,” she said.

District 59 special education teacher and Chicago Public Schools parent Maureen Hehir and her three children, sixth-grader Sinéad, third-grader James and first-grader Emmet. (Courtesy of Maureen Hehir)

Dunn, following the conversation with Arwady, noted that remote learning and work stoppages have been a “catastrophic failure” for Black students, contributing to an increase in crime and mental health problems. She pointed to news reports of children accused of carjacking. And according to the Children’s Hospital of Chicago, 44 percent of young children have experienced an increase in mental health or behavior problems during the pandemic.

Whether leaning more toward reopening schools as soon as possible or pausing in-person learning, Chicago parents said they want more representation at the city level.

“We should have a Chicago parents union,” said Wade, the parent liaison. “We should be as strong as the mayor’s office and as strong as the Chicago Teachers Union.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)