Case Study: How One Texas School District Is Repurposing Staff Development Time to Embrace the Science of Reading

Unleashing the power of professional learning communities through richer, curriculum-based learning in the Aldine Independent School District.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This is the next installment in a series of articles by the Knowledge Matters Campaign to elevate stories of educators implementing high-quality instructional materials. Edna Cruz is a bilingual skills specialist and Alaura Mack is an instructional skills specialist working together at Reed Academy in the Aldine Independent School District, which includes parts of Houston and Harris County, Texas. As the first distrct in Texas to have adopted a high-quality, knowledge-based reading curriculum, the authors reflect on the importance of equipping teachers with curriculum-based professional learning to ensure long-lasting success for students. Follow the rest of the series and previous curriculum case studies here.

In 2020, the Aldine Independent School District became the first district in Texas to adopt a high-quality, knowledge-based reading curriculum. It was a seismic change for teachers, who had been using a familiar balanced literacy program with skills-focused lessons and leveled readers for several years. But it was a necessary change for students — in 2018-19, just 30 percent of Aldine third graders were reading at or above grade level.

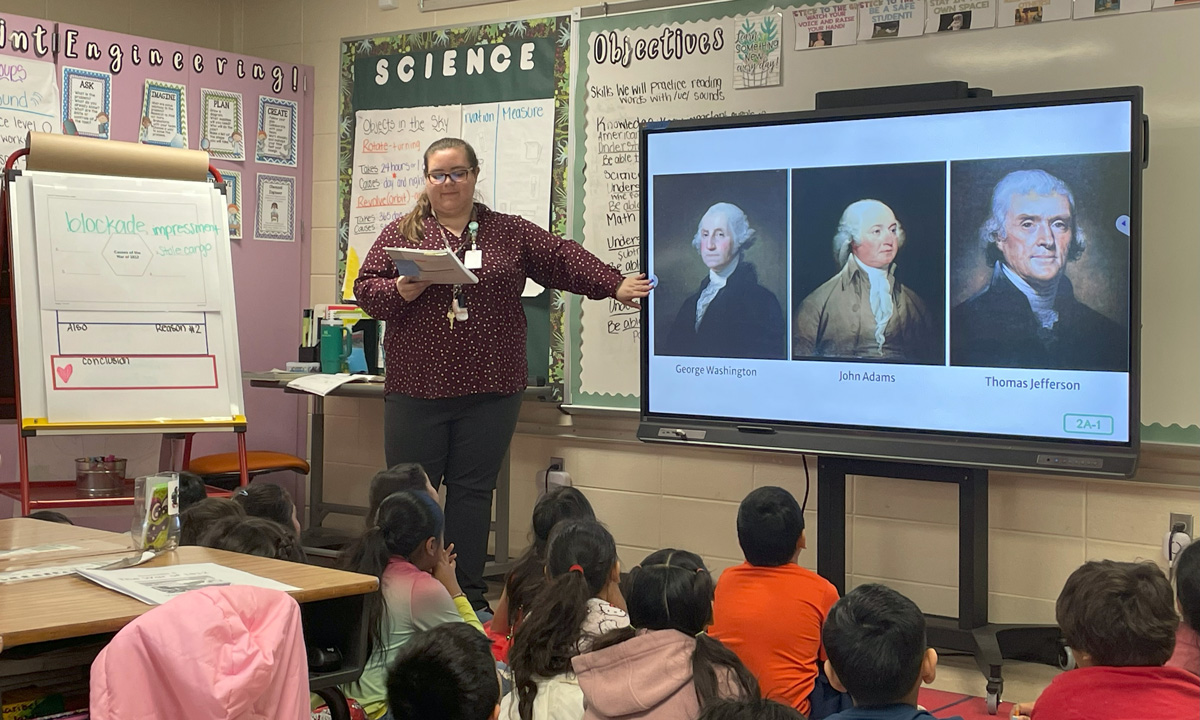

Despite the challenges of COVID-19 and its effect on academic achievement, we have made strides by implementing the Amplify CKLA curriculum. Today, teachers lead highly structured, thematic units that focus on the same content over a period of weeks. All students work with the same knowledge-rich, grade-level texts, whether they read them independently or with support. That gives every student the opportunity to build vocabulary and a base of common knowledge, which boosts reading comprehension and fosters inclusive communities of learning.

Our students have made rapid progress — within the first two years, 50 percent of third graders were reading at or above grade level. The percentage of third graders scoring “well below” benchmark dropped from 48 percent to 36 percent. These are heavy lifts in Aldine, where about 90 percent of students are economically disadvantaged and more than half are English language learners.

Students’ academic achievement and development rely on their teachers’ understanding and execution of the Amplify CKLA curriculum. As instructional specialists, we have implemented robust curriculum-based professional learning to ensure Aldine teachers are prepared to deliver strong instruction that meets the needs of all students.

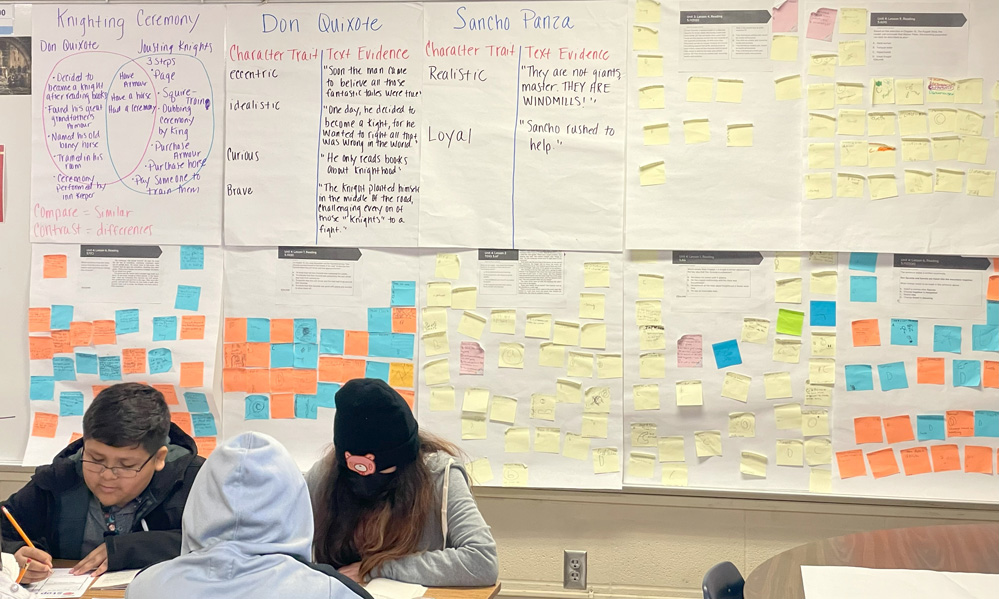

Curriculum-based professional learning brings teachers and instructional leaders together to probe and practice individual lessons, which has helped our teachers implement new curriculum with fidelity. During these sessions, teachers internalize, annotate, collaborate, and rehearse lessons within units of study. They identify the most critical ideas and skills students should encounter, the most likely misconceptions students may experience, and the scaffolds or learning supports needed to grant access to the content to all learners.

This sort of study doesn’t happen overnight. Here are three key aspects of this work that have shaped our progress:

Closing the Research-Practice Gap

Too often, research stands a world apart from the educators who work directly with students.

Aldine provided resources and time to close that gap. Even before the new curriculum was announced, both teachers and instructional specialists like us read Natalie Wexler’s The Knowledge Gap and participated in related staff development sessions. Meanwhile, a literacy task force was studying curriculums and visiting out-of-state classrooms to make their recommendation.

This shared reading assignment and attendant discussions helped teachers and specialists learn the science behind best practices and understand the role that building knowledge plays in literacy development. Both were critical when it came time for our teachers to trust that an unfamiliar and seemingly out-of-reach reading curriculum could be effective in Aldine classrooms.

Revamping PLCs for Curriculum Study

In the past, meeting time for professional learning communities (PLCs) was spent on grade-level “business,” like planning field trips or sharing concerns from individual classroom observations. These are key issues, but they don’t necessarily translate into instructional innovation or academic progress.

Even when meetings were focused on instruction, master teachers and teachers with outsized experience or confidence spoke up most often. As a result, meetings did not include the voices of all teachers, especially novices or those serving the most disadvantaged student groups.

Our district revamped grade-level meetings to focus on in-depth curriculum study. Today, during Curriculum-based Professional Learning (CPLs), instructional specialists facilitate in-depth curriculum study sessions, which follow detailed discussion protocols. These one- and two-page discussion guides help teachers unpack and internalize the logic of each unit and lesson, identify opportunities to make cultural connections with and among students, and focus attention on the essential questions and tasks each lesson needs to ensure students master the learning goal.

This structure and guidance help ensure teachers’ time together is purposeful and driven by our common curriculum. In addition, by focusing attention on a shared resource, we’ve seen that more teachers speak up in CPLs, which gives a grade-level group a wider view of classroom practice and learning.

Building Teachers’ Trust

Changing curriculum means changing instructional practice and underlying beliefs. Teachers need to trust that a new curriculum will work with their students before they will teach it as intended.

Often, teachers who work with struggling students are initially wary of high-quality, knowledge-based curriculum. In our district, second-grade teachers were concerned that students would not successfully engage with a unit based on grade-level texts about The War of 1812, for example.

Ongoing curriculum-based professional learning with grade-level colleagues helped address these concerns. As teachers studied and practiced units and lessons together, they could see the logic and variety of ways students at all levels could access, understand, and make connections with rigorous content. And, as they experienced this new teaching in their classrooms, they could share challenges and evidence of growth. No one teacher was going it alone.

Any change in curriculum requires strong leadership from the Central Office. But when it comes to changing what actually happens in classrooms and schools, teachers are the real decision-makers. By intentionally equipping teachers with curriculum-based professional learning, we are setting our schools up for long-lasting success.

Edna Cruz is a bilingual skills specialist at Reed Academy in the Aldine Independent School District, which includes parts of Houston and Harris County, Tx. She is a member of the Curriculum Matters Professional Learning Network, which supports district leaders from around the country implementing high-quality instructional materials. Alaura Mack is an instructional skills specialist for English Language Arts at Reed Academy and is also a member of the Curriculum Matters Professional Learning Network.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)