Building Oral Language Skills and Equity Through High-Quality Reading Curriculum

How knowledge-rich curriculum is helping English Learners in New Mexico make rapid gains.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This is the next installment in a series of articles by the Knowledge Matters Campaign to elevate stories of educators implementing high-quality instructional materials. Karla Stinehart is the director for elementary education at the Roswell Independent School District and a member of the Curriculum Matters Professional Learning Network, which supports district leaders from around the country implementing high-quality instructional materials. She reflects on how important knowledge-rich curriculum is for ELL students and how far Roswell has come in a relatively short time. Follow the rest of the series and previous curriculum case studies here.

Picture this: kindergarten students are excitedly discussing the life cycle of a tree. In a whole-class discussion, paired “turn and talk” chats with a partner, and responses to sentence stems, they describe bare limbs, falling leaves, and a tree’s dormant winter season. They compare evergreens and deciduous trees, using vocabulary that reappears in related texts. In this joyful learning community, students at all reading levels practice grade-level oral and literacy skills, grow vocabulary, and gain access to a common base of information.

This is what reading lessons look like today in the Roswell Independent School District, where I oversee elementary education. It’s a major difference from the not-so-distant past.

In Roswell, more than 75% of students are Hispanic and about one-third are English language learners. More than one-third are from low-income households. For many of our students, kindergarten is their first classroom experience. They haven’t yet mastered the oral-language skills needed for learning, like answering and asking questions in complete sentences, turn-taking, and following directions. Because these skills form the foundation for academic learning, building oral language and vocabulary are urgent priorities.

Five years ago, teachers would group students and assign texts by skill level and rotate between groups to offer targeted supports. While this approach was familiar to many of our educators, we also recognized that it wasn’t accelerating learning for the students who needed it most. Learning is a social activity, and students thrive when they can participate fully with their classmates. By keeping students separated, we were perpetuating differences in their levels of preparedness for school.

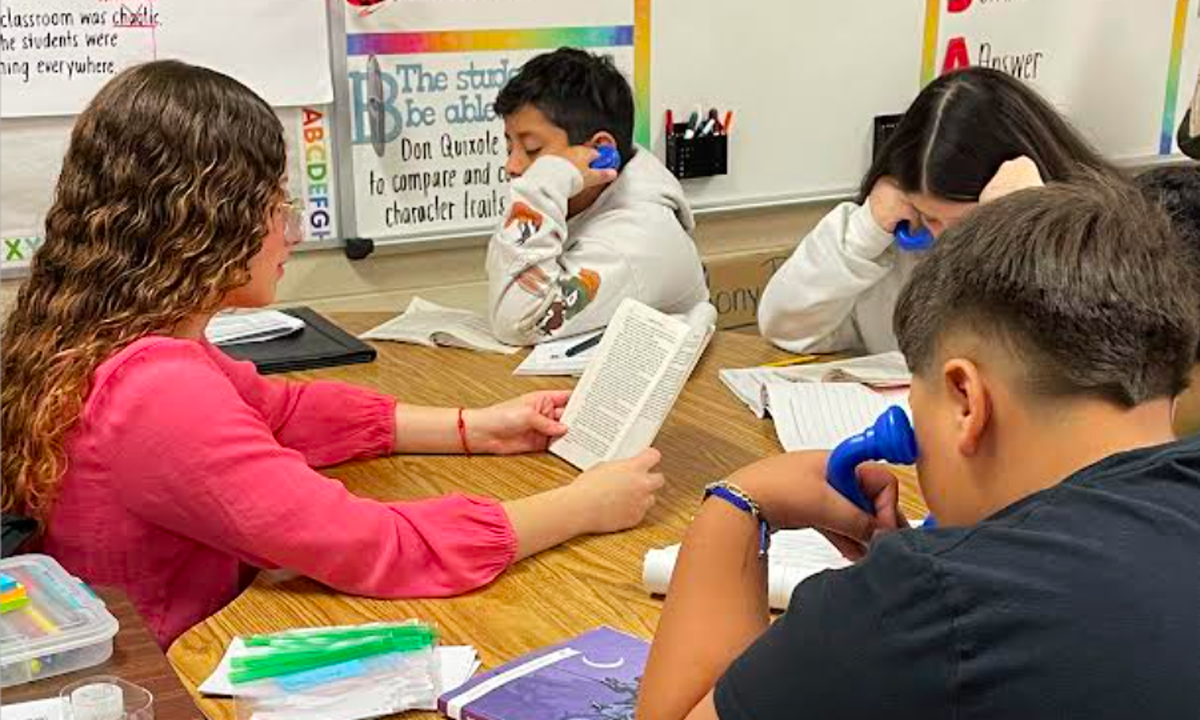

Today, our teachers are using a new, knowledge-based high-quality reading curriculum and students of all language levels work together with texts on a common topic. Students’ interaction with these texts can vary — some read independently, some in pairs, some in small groups, and some listen as the text is read to them. But they are working with the same vocabulary and building the same knowledge. In these classrooms, it’s hard to spot students who are working to catch up with their peers, because the entire class is working together on the same grade-level content.

This transition didn’t happen overnight. There were three major moves that have helped us to adopt and implement a high-quality, knowledge-based reading curriculum.

Go Grassroots—But Be Ready to Leverage Leadership

Before we entertained switching curriculum, we invested in building knowledge and expertise about the science of reading in our district. Along with two-dozen colleagues, I participated in the LETRS professional learning program to learn about structured literacy. Some of those educators had been working to nudge our instruction toward evidence-based practices, but there was little momentum to do so across the board.

When our leadership changed and New Mexico passed a new literacy law, there was an opportunity to reassess current practices. Because we had already built a deep understanding of the science of reading, we were able to make the case for a new curriculum and include a variety of perspectives in choosing the right program for our students.

Administrators, reading coaches, and teachers worked together to ensure the curriculum we chose, Amplify CKLA, is truly aligned to the science of reading. Better yet, we could base on decision on our earlier studies, not a sticker or marketing slogan.

Begin With the Believers and Share Their Success

Changing teacher practices is hard. But changing teacher beliefs is even harder. Teachers are motivated by seeing evidence of success from trusted colleagues. And so we rolled out the new curriculum in three waves, not all at once, and were intentional in deciding which educators went first. We also established internal communications channels to share their success stories across the district.

Our first group included principals who were fully on board with the switch and teachers who were part of that grassroots science of reading movement. They were excited to shift instruction and share their experiences with colleagues. The second group included educators who were hesitant and looking for someone else to take the first step. The last group included teachers who were not eager to move away from traditional instruction.

We capitalized on the energy and expertise in our first group of curriculum switchers by sharing their experiences with educators in the second and third waves of the rollout. Our internal communications director filmed teacher testimonials, which were posted on our website. I shared these videos with our elementary principals, and they also were featured in grade-level professional learning communities.

Respond to Teacher Concerns

A knowledge-based curriculum is necessarily topic-driven. Some teachers were concerned that parents could object to certain topics. For example, a second-grade unit about early civilizations includes information about archeology and world religions. Teachers flagged that reading about various religious could be a potential point of contention for families.

We reviewed our policies and reassured teachers that they would be fully supported and had established procedures to follow if a question was raised. Teachers could share the curriculum with parents and, if a family objected, did not have to resolve the issue on their own. An administrator could help provide an alternative. We reassured them that their job is to teach the curriculum as it is written. If there’s a question or concern, a principal or administrator like me is ready to handle it. And we haven’t experienced this sort of issue to date.

All students deserve to have access to grade-level rigor, vocabulary, and content. But not every child gets to experience holiday travel, weekend museum trips, or other opportunities to build their knowledge about the world. High-quality, knowledge-based curriculum empowers students with new tools to communicate and shared knowledge to speak and write about. If we don’t provide this opportunity to all students, we are essentially shutting the door on those least prepared to thrive in school.

Karla Stinehart is the director for elementary education at New Mexico’s Roswell Independent School District and a member of the Curriculum Matters Professional Learning Network.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)