Updated

Families can drastically underestimate how often their children miss school. When researchers asked parents whose kids clocked nearly 18 absences in one school year how many days they thought their child had missed, they thought it was more like 10.

But when parents are given accurate information about their children’s absences, new research shows, they can become valuable players in making sure their kids show up at school. The study, published in Nature Human Behaviour, found that sending parents mail multiple times over a school year informing them how many times their child had missed class reduced chronic absenteeism by 10 percent.

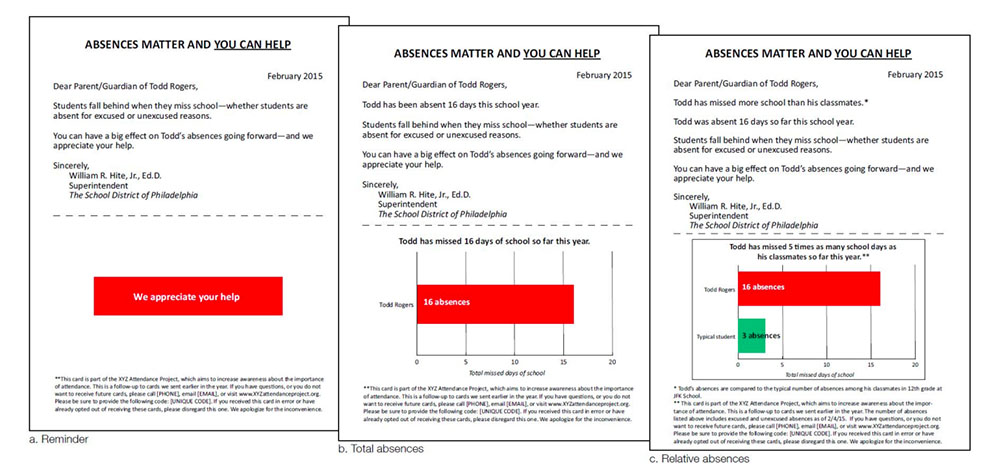

In a randomized control trial, researchers sent different types of mail to 28,000 families in the school district of Philadelphia during the 2014–15 school year. One group received mail that said absences matter and they could help their kids get to class. Another group received the same message, but with a tracker showing how many days of class their children had missed so far. A third received a letter not only tracking their kids’ absences but showing their classmates’ average absences as well. A control group received no information from the study team.

The letter that proved most effective — reducing chronic absenteeism by 10 percent — was the one that simply reported the total absences over time. This surprised researchers, as they thought comparing students’ absences with their peers’ might be more motivating for parents.

A survey conducted at the end of the study found that parents could more accurately guess their kids’ attendance at the end of the year if they had received letters with the trackers, suggesting that the information influenced their perception, researchers said.

The cost of mailing was $6.60 per household, but because the intervention generated an additional 1.1 days of attendance per household, the program proved cost-effective, bringing the price to $6 per additional day (schools lose significant amounts of state funding when students are absent). It was also much less expensive than other programs that have helped boost attendance: for example, a mentoring program in Chicago reduced absenteeism by 3.4 days in grades 5–7, but it cost $500 with each additional day of attendance that it produced.

Researchers and attendance advocates pointed out that this new approach should be viewed as part of a larger plan to reduce chronic absenteeism, defined as missing 10 percent of a school year.

“If districts or schools didn’t take [chronic absenteeism] seriously before, I hope this evidence pushes administrators and principals to think harder about these very low-cost, simple interventions that could be part of a larger intervention,” said Avi Feller, assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who co-authored the study with Todd Rogers of the Harvard Kennedy School.

Part of what makes this intervention powerful is how it prioritizes creating and sharing data with parents, said Hedy Chang, executive director of the nonprofit Attendance Works. Chang’s organization recommends three types of interventions to address chronic absenteeism in schools, and the first includes building these relationships with families.

But this intervention alone is not enough for schools with students who face significant barriers to attending class, like transportation, a lack of clean clothes, illness, and family obligations. Schools have to create action plans to ease those barriers, Chang said. Punitive measures should only be a last resort, she said, especially because families in poverty aren’t always aware of their kids’ absences with the additional stressors they need to deal with.

“My biggest fear,” Chang said, “is that our traditional approach to poor attendance is to just blame kids and families when what you really need to do is treat them with respect.”

The most recent estimate puts the number of students nationally who are chronically absent at 8 million, as tracked by the Office for Civil Rights. Chang has pointed out difficulties in the way the self-reported data from districts is counted. For example, some districts count absences by class period missed, while others count it by half-days.

Still, many states have made progress in prioritizing addressing chronic absenteeism. Under the Every Student Succeeds Act, 36 states and the District of Columbia have made chronic absenteeism one of their accountability measures.

Addressing chronic absenteeism is important because research has shown that absences predict not just academic performance but also graduation, substance abuse, and criminal activity. And the price tag for missed classes is huge: Officials in the Los Angeles Unified School District reported last year that chronic absenteeism cost $45 million in state revenue over one year.

Chang said the best, scalable approaches to chronic absenteeism don’t necessarily need to involve creating new interventions in schools, but rather should entail learning from research recommendations and incorporating them into existing programs.

“We communicate with families all the time,” Chang said. “Do we communicate the right things?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)