Cami Anderson: Disparate School Discipline, the ‘Dear Colleague’ Letter, and Civil Rights — 5 Key Points That Get Lost in All the Noise

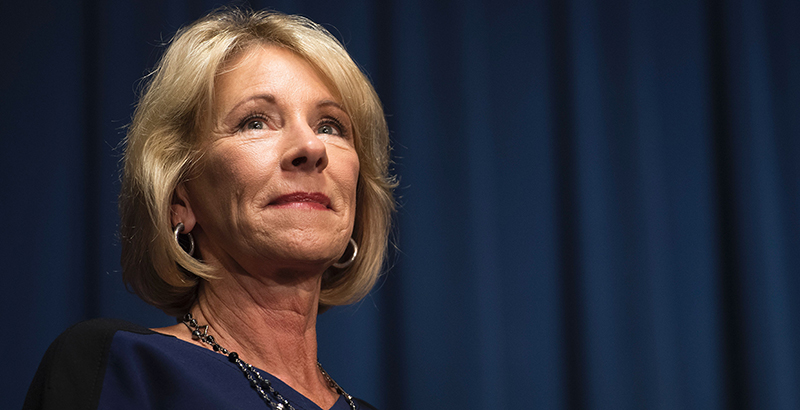

Last week, we saw national headlines about two seemingly disparate events: the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, and the crescendo of a national debate about whether Education Secretary Betsy DeVos should rescind Obama-era guidance about school discipline. These two milestones have more in common than many people think.

For those not following the debate about student discipline closely, in 2011, the Council of State Governments published a methodical and rigorous study of student-level data from around the country. The study, Breaking Schools’ Rules, found that black students, particularly African-American boys, are disproportionately suspended and excluded from school, compared with their peers. Subsequent research around that time, including data from the federal Civil Rights Data Collection, found that students with disabilities are also disproportionately punished, compared with their peers. Other studies in the past five years have pointed out that LGBTQQ — lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning — students face similarly disparate discipline.

In response to this growing body of evidence, in 2014, the U.S. Department of Education issued guidance to inform educators that federal laws prohibit discriminatory discipline practices and that the Office for Civil Rights could investigate districts and schools that are out of compliance with those legal requirements.

Many advocates and educators, like me — at the time, I was the superintendent in Newark — felt the letter was a commonsense, welcome light shined in dark corners, and a rallying cry for collective action.

Surprisingly (to me at least), the guidance has become a passionate cause for right-leaning think tanks and some politicians. Their arguments take many forms. Some believe the disproportionate data are explained by life circumstances rather than bias. Some say the advocacy is a classic case of federal overreach, tantamount to Washington telling teachers what to do. Some have tried to make the case that the guidance spurred “discipline reform” that has made schools more chaotic and less safe.

As with many issues in our current discourse, key points that we should be talking about have gotten lost in an ideological food fight.

Here are five points for discussion:

The facts are the facts. An independent report issued by the objective and bipartisan General Accounting Office just last week affirmed the obvious: Exclusionary student discipline affects black students far more than their white peers. As one example, African-American students make up 55 percent of school-based arrests even as they comprise only 16 percent of the student population (and 0 percent of the perpetrators of mass school shootings). Another example: Recent studies show that black boys are far more likely to receive negative teacher attention than their peers (often for the same behaviors in kindergarten), and African-American girls are thought to be “less innocent” than their white peers. And while wonky types like to argue about whether the data are causal or correlative, being in serious trouble in school means a substantially increased likelihood you will be involved with the justice system for the rest of your life. Adult biases are at play, and they push kids into a criminal justice system where the same biases can end their life.

The law is the law. King died four years after one of his signature accomplishments: passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination and segregation on the basis of race, religion, national origin, or gender in the workplace, schools, public accommodations, and federally assisted programs. Title VI of that act went on to further clarify that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to discrimination under any program receiving federal financial assistance. Federal guidance or not, “Dear Colleague” letter or not, the federal government has a legal mandate to uphold the law. If those who oppose the guidance — which simply gave further information about how this relates to school discipline — wish to relitigate the Civil Rights Act, they should be bold enough to say this is their intention.

Yes, support for schools and building capacity matters. One thing about which some right-leaning think tank leaders and I can agree: We must replace antiquated practices with new ones. We can’t simply be against suspensions and expulsions; we have to be for a new set of policies and practices — and we have to invest in training, support, and coaching for teachers, student support staff, school safety agents, administrators, families, and organizations that work alongside schools. Policy alone is not the answer, but it is certainly an important piece of the puzzle. Many conservative politicians and thought leaders seem to abandon their belief in holding schools and educators accountable for results when it comes to disproportionality in school discipline data.

Blame won’t solve the problem. It is tempting for district schools to suggest charter schools are the biggest offenders of disproportionate discipline — and for charter schools to say districts are incapable of solving problems. It’s easy for teachers to say principals are the problem, principals to say teachers are the problem, schools to say families are the problem, or families to say other families are the problem. Where we see progress on this issue, we see people working together to build the skill and will of all the adults in a community to prevent incidents in the first place and to respond to children in developmentally appropriate ways when they do occur.

What matters most: upholding students’ civil rights. What does the anniversary of King’s murder have to do with the current debate about school discipline? The very law that he and so many others fought to enact is about establishing the federal government’s role in ensuring that citizens are free from discrimination when accessing public institutions. From an educational standpoint, this means protecting students’ civil rights. The federal government is responsible, by Constitution and law, for ensuring that the societal inequities that exist because of race, class, ableism, and sexual identity are not cemented in schools.

King implored us all to act with the “fierce urgency of now” when it comes to realizing a day when all citizens have equal rights. Let’s keep the focus first on supporting schools and families to ensure that all young people, not just those we perceive to be compliant, thrive and excel. We need to embrace an approach that builds the capacity of schools to support the healthy identity of every student — and holds them accountable for creating bias-free environments in accordance with civil rights laws.

Cami Anderson, superintendent of Newark Public Schools from 2011 to 2015 and superintendent of alternative high schools in New York City (including the suspension centers and the schools on Rikers Island) from 2006 to 2015, is the founder of the Discipline Revolution Project, a coalition of education leaders working to find new approaches to school discipline.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)