By the Numbers — How 100 School Systems Are (and Aren’t) Adapting to COVID: As Some Districts Use Test-to-Stay to Avert Quarantines, Majority Don’t Require Testing

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This the latest in a series of weekly analyses of COVID-19 policies in 100 large and high-profile school systems, produced by the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington, Bothell. You can see the full archive here.

As all of our nation’s schools have reopened for the new year, and many communities continue to face rising infections, one of the best defenses against school disruptions may also be one of the least contentious: COVID testing.

Testing can complement masking, vaccination requirements and proactive parent communication, and it can help schools lower infection rates while minimizing quarantines.

But our review of 100 large and urban school systems suggests many districts are not systematically taking advantage of this critical tool.

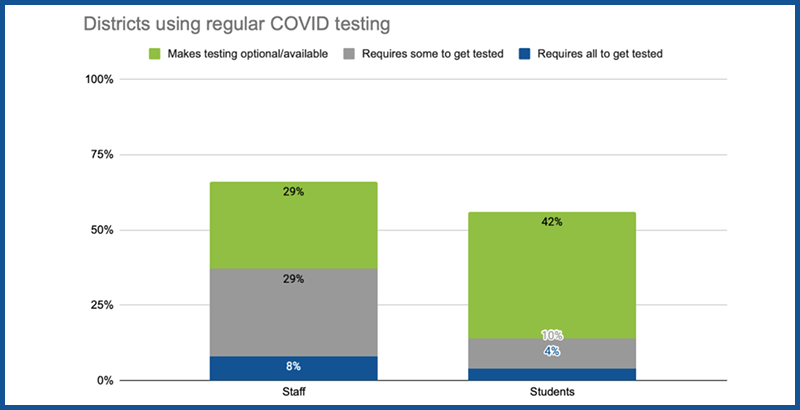

About half the districts in our review either mandate regular testing or rely on optional testing to identify new cases, with 37 requiring testing for staff and 14 for students.

Eight districts require staff to undergo testing, usually weekly, even if they are vaccinated. Twenty-nine require testing for some staff members, such as those who are unvaccinated. Another 29 districts offer optional testing for staff.

While student testing mandates in New York and Los Angeles grabbed headlines when school resumed, such requirements remain uncommon in the rest of the country.

Four districts in our review, including L.A. Unified, require all students to undergo regular COVID screening. Ten districts require some to undergo preventative testing, such as children who are unvaccinated or play sports. D.C. Public Schools is randomly testing at least 10 percent of students each week, targeting unvaccinated kids.

Test-to-stay is a new tool aimed to shorten quarantine time

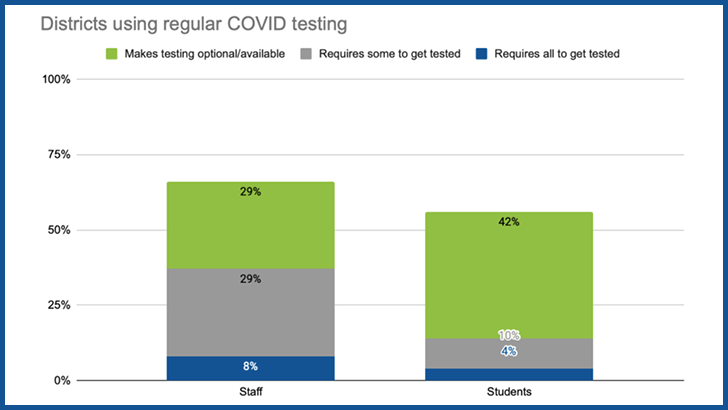

Testing can help administrators detect COVID infections before they spread in schools, while limiting the number of students who have to quarantine. Every district we track has now clarified its quarantine policy, and a growing number offer exemptions to students who take other precautions to safeguard against the spread of the virus.

Of the 100 districts we review, 86 exempt vaccinated students from quarantine, with 69 specifying that the exemption applies if they do not show symptoms. Other exemptions include students who recently recovered from COVID (37) and exposed students wearing masks (29).

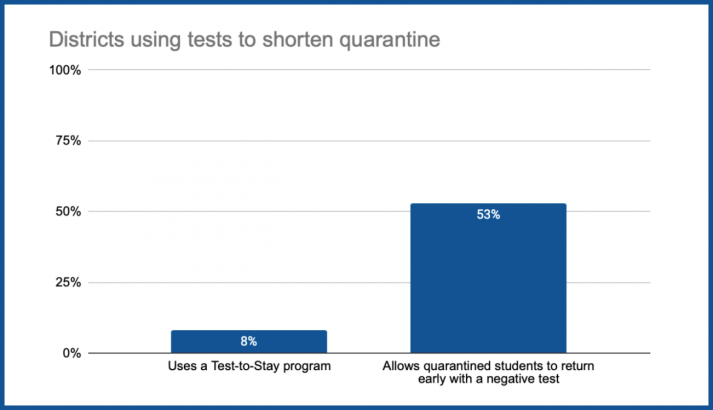

Districts are increasingly turning to testing to limit quarantines. A little more than half of districts in our review (53) allow students who test negative for the virus to shorten or avoid isolation.

A few districts (8), in an attempt to keep more students learning in-person, are modifying their approach to quarantine using a test-to-stay program. These policies allow students who may have been exposed to the virus to continue in-person learning as long as they take daily COVID-19 tests.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has not yet approved the test-to-stay approach and continues to recommend quarantine for up to 14 days for certain students. The federal public health agency told The New York Times it does not recommend test-to-stay but is working with local jurisdictions to collect more information on the strategy and its execution.

A handful of states, including Illinois, Kansas, California and Massachusetts, have now outlined test-to-stay protocols or similar rules that let schools use testing to ease quarantine requirements. Seven of the eight districts with test-to-stay policies are located in these states. Portland Public Schools, in Maine, is the only district in our review administering a test-to-stay program without state guidance.

In other cases, state policies might prevent districts from adding nuance to their quarantine policies. New Hampshire asks students or staff who are under quarantine to stay home for 14 days after their last exposure to an infected person, monitor for symptoms and seek testing. A negative test does not shorten the length of time a student has to quarantine.

Testing may be an especially valuable tool in states that limit other health precautions, like Florida and Texas, whose governors have banned mask mandates, or Montana, which passed legislation that prohibits discrimination against individuals based on their COVID-19 vaccination status.

More districts signal vaccination requirements, but lack clarity on enforcement

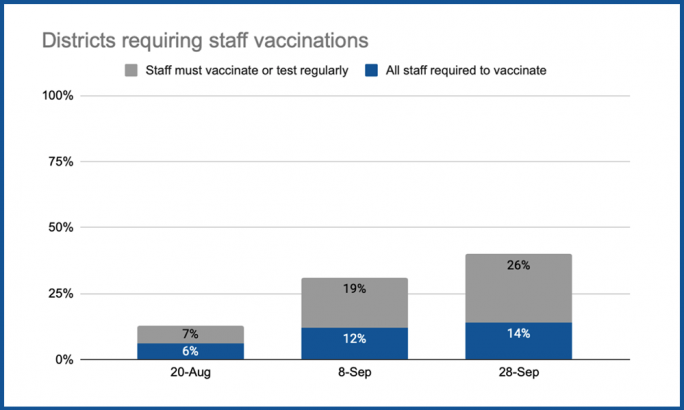

Following the Biden administration’s recent, sweeping mandates for federal workers and businesses, a few more districts are following suit, with 40 in our review now requiring staff vaccinations. Of those, 14 require all staff members to get vaccinated without a testing alternative. This is double the number of districts with vaccine mandates a month earlier, but it is far outpaced by the growing number that allow staff to opt out through regular testing.

San Antonio ISD became the first district in Texas to require staff vaccinations, a decision that violates the governor’s executive order and has sparked legal battle with the state.

Meanwhile, 26 districts now require staff to either get vaccinated or participate in weekly testing. The School District of Philadelphia requires unvaccinated staff to get tested twice a week.

L.A. Unified and the Oakland Unified School District remain the ones that require vaccinations for all eligible students. Another California district, San Diego Unified, recently approved a requirement for students over 16. Eight districts require student athletes to get vaccinated.

As early as January, all eligible K-12 students in California will be required to get the vaccine. Gov. Gavin Newsom issued the nation’s first statewide mandate on Friday.

State, federal leadership needed to help districts take advantage of testing

District leaders face the critical work of protecting students’ health, keeping them learning in classrooms wherever possible and helping them recover from the academic and emotional toll of the pandemic. They cannot afford to waste precious time and attention battling state officials or teachers unions over health precautions. Nor can students afford to have this school year interrupted by excessive quarantines.

Testing can be a valuable tool for catching outbreaks early in schools. It can work in concert with masking, vaccination and quarantines — or provide critical protections in districts where political barriers are blocking these crucial health precautions. And research suggests it can provide a safe, effective way to reduce the interruptions caused by quarantines while guarding against infections in schools.

State and federal leaders should enact guidance that helps districts make the most of this critical tool. State education and health offices must come together to provide the funding, policy guidance and coordination so districts can conduct reliable testing at scale.

Locally, health authorities can pool resources and share protocols. And they should help districts find creative ways to overcome one of the biggest logistical barriers to robust COVID testing programs: a lack of staff. As one district official in Texas told The Times, “I need an army.” That army could include parent volunteers, school system workers, employees from community organizations or personnel from local health agencies.

There is still much we don’t know about the barriers preventing schools from implementing effective COVID testing programs. Until more districts start enacting testing programs and talking openly about the operational barriers, it may not be clear exactly what states, health agencies and community volunteers can do to help.

Bree Dusseault is principal at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, supporting its analysis of district and charter responses to COVID-19. She previously served as executive director of Green Dot Public Schools Washington, executive director of pK-12 schools for Seattle Public Schools, a researcher at CRPE, and as a principal and teacher. Christine Pitts is a resident policy fellow at the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)