Beyond the Scantron: College Board’s Chakravarty Says the Pandemic’s Big ‘Aha’ Moment on Assessments Was Less About Tech, More About the Challenges of Equitably Testing at Home

This interview is part of “Beyond the Scantron: Tests and Equity in Today’s Schools,” a three-week series produced in partnership with the George W. Bush Institute to examine key elements of high-quality exams and illuminate why using them well and consistently matters to equitably serve all students. Read all the pieces in this series as they are published here. Read our previous accountability series here.

Auditi Chakravarty is senior vice president of learning, evaluation and research at the College Board. She taught English and developed curriculum before joining Kaplan Test Prep and then the College Board.

The University of Illinois graduate emphasizes that high-quality tests are only one means of getting information about a student. But, she says, such tests can provide relevant, important information to parents, students and educators alike. She also details how tests like the SAT are created and how tests should be used to serve a purpose.

What role do high-quality assessments play in teaching and learning? And how do you think of them in terms of accountability and policy?

Let me first say assessment is only one of many ways to get information that can be useful to a teacher, a principal, a district, a policymaker or a college. Whether an assessment is the best source of information depends upon the purpose. High-quality assessments provide information in standardized form about how a student is tracking against an outcome that we as a public have said is important for a student to achieve.

If a test is high-quality, it means that the goals are right, that the standards we’ve aligned them to are the right ones, that the skills that we’re measuring are the right ones and that the assessment provides complete equal opportunity for students to do well. If those things are true, then the information that you can get out of that test can be very powerful.

The big question in the room is how we should use testing as students come back for the 2020-21 school year. So, what should we be thinking about?

My foremost concern is that the focus this year should be on learning. High-quality formative assessments can be useful measures of learning, showing where learning gaps exists, and which students suffered more than others by the disruptions.

Assessments could be useful this year for making sure that students get the opportunity to learn, that teachers get the support that they need and that schools have the resources that they need in the places that matter.

Is there an opportunity to do some of that with the big tests you have?

A well-designed standardized test certainly provides a measure that you can use for this type of information. The PSAT and SAT, for example, function together as a suite. The SAT is the summative assessment, while the PSAT is intended to show where students are at a particular time. They give parents, students and teachers a sense of what they need to work on. And each time they take it, it shows how well they are progressing. So, the PSAT in particular can play a role in assessing where students are — if school openings allow that to be done safely.

Could you talk about how the PSAT and SAT are constructed for content and how they are scored? I know many parents and students would like to know that last part.

I love that question because not enough time is spent talking about the meticulous process that goes into the design of an assessment like the PSAT or the SAT. There is a lot of up-front design work that requires a lot of thought and planning.

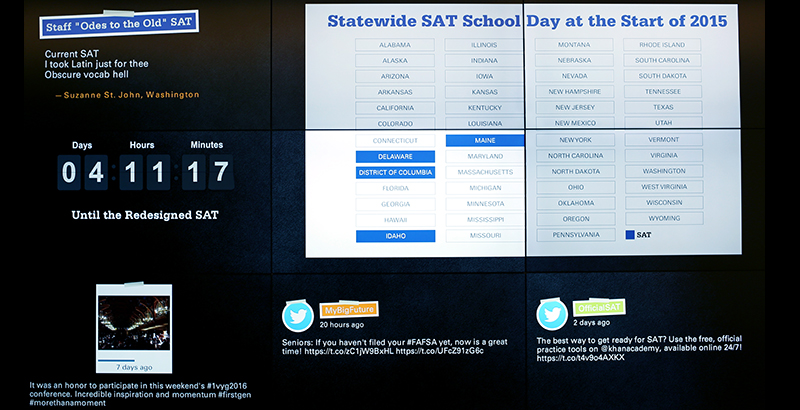

The most recently redesigned SAT took a couple of years of up-front design work to home in on the knowledge and skills that matter within each discipline, that are important to test, and that the end user cares about. By that last point, I mean what colleges tell us they want to know from a test score. With all of this in mind, we go through a methodical process to design the individual items that students will see.

The process starts with testing questions with students in order to make sure that they measure what they’re intended to measure. We do that early in the design process, but then throughout our development work we do extensive pre-testing to make sure items are fair, that they don’t discriminate against one population or the other, and that they perform the way that we want them to perform.

For instance, sometimes you put out a passage with a question and realize that most students didn’t get what was being asked. That is a bad item that we must throw out. It is not going to measure what it’s intended to measure.

On the scoring front, you ensure that the raw scores are comparable to prior years’ scores. In addition to careful item and form development, this happens through a process we call equating, where scores on every test form are aligned to previous years’ test forms. That allows us to say that a 1420 this year on the SAT is equivalent to a 1420 on last year’s SAT.

Sometimes people say they saw a released form and two items looked easier than what they had on their SAT. Equating takes care of that. We use the actual performance data of students who took the tests to make them equivalent. This is an essential part of our test design and development process, ensuring that forms are comparable.

Could you talk about the kinds of people who are involved in that work? What kind of experience and expertise do they have?

It is a combination of people. We have College Board staff who are subject area experts. In the SAT and AP programs, we have a lot of former teachers and professors across many disciplines. They have deep knowledge about their disciplines.

We also have people who have expertise in testing itself. They’re the measurement people who understand how to do things like equating. They understand the statistical methods we use after we pre-test an item to determine whether it performed fairly or not.

It often gets overlooked that we are a membership organization that works with colleges and high school educators on developing our tests. We have an SAT committee that we confer with regularly and from whom we take recommendations. These are not just college admissions people. They also are college faculty as well as high school educators. We consult with them to ensure that our content specifications and design work are sound.

In the case of AP, the committees develop and review all items and finalize the forms. An internal content expert shepherds that process, working with external content and area experts as well.

So, there are a lot of people with deep education expertise, instructional expertise, content expertise and domain expertise. They work alongside people who understand assessment development and the statistics of assessment.

Because of the pandemic, students took AP tests online in the spring. What did you learn from that experience about fair, equitable ways to deliver tests online, especially as test-taking evolves technologically?

We learned a lot about technology and assessment. The big “aha” was less about technology and more about testing at home.

Technology absolutely does matter. It’s critical that students have access to bandwidth and high-quality internet that doesn’t drop every five minutes while they’re in the middle of a test. And they need a device they can use for the hour it takes them to test. We supported schools and families in getting students access to these essentials. But we need greater equity if we must do at-home testing at scale in the future.

That said, students also noted in surveys that other distractions — family members, the sounds of outdoor activities — were a challenge during testing. In fact, many more students were challenged by the myriad distractions of testing at home than by technology issues.

We hope we can offer all or most AP tests at school this year for all these reasons, especially the equity reasons. But it is exciting to have greater technology capability than even just a few years ago. I think that will only continue.

As more states have adopted the SAT as their high school state test, are they using them for teaching and learning? For accountability? For college admission? And has the greater use of the SAT or ACT changed how you think about the design of the test, such as how you work with the community?

When states choose to adopt the SAT for accountability purposes, they become a close partner with us. We have to think about the test differently, but it also creates opportunities. Using the SAT for accountability also often leads to the PSAT playing a role. We don’t want the SAT to just be a summative gotcha exam. We want to make sure states — and educators and families — are getting information along the way so that they can use the data for specific strategies.

For example, one state that is using the PSAT and SAT wants to help students prepare not only for college but also career. Our Career Finder tool was built, in partnership with Roadtrip Nation, in response to their need. Each state might be looking for different things, so we work specifically with them on their goals.

In terms of the design, these partnerships keep us honest. Our latest redesign was informed by what states told us they need. We want to make sure everything is aligned and that the test is providing the right information if states adopt the SAT as an accountability tool.

Interestingly, research has shown that in states where there has been a statewide adoption of a college entrance exam, it can increase the application and admission rates of underrepresented students. They might not have taken the SAT before, but now that their state has them do it for their accountability system, the students see the opportunity shows their abilities to colleges.

What would you say to the many universities and colleges opting out of the SAT or ACT about the importance of these tests in broadening college admission?

It’s a tough situation this year. We support their reasons for opting out. We have encouraged institutions to adopt flexible policies because many kids won’t have the chance to take the test, to practice, or to retake the test to try to improve their score.

In general, I go back to what I said before: Tests are only one piece of information in the college entrance calculation for the admissions officer. Colleges should look at the test in the context of all the other things that they care about, and without the test, they must rely on the other information they have.

Beyond this year, I would say to colleges that you should get as much valid and reliable information about each student as you can that aligns with your goals. As one, standardized piece of information, tests can be a useful part of the admissions and enrollment process.

Our research shows that grades and test scores used together are more predictive of college outcomes than either one of them used alone. Grades on their own are very, very slightly more predictive than the SAT, but the two together are powerful.

What worries you — and excites you — about assessment in five or 10 years?

What would worry me is if assessment disappears altogether. As I said, assessments do provide useful information when used in context with other evidence.

In a high-quality assessment, the skills that are being tested are those worth teaching. The tests can help teachers focus when designing instruction. For instance, as a former English teacher, I can look at the PSAT and SAT reading tests to see how my students are doing with important reading, vocabulary and writing skills. It can help me think through what I can do better.

I worry that in the criticisms and critiques of assessment, some of which are warranted, but many of which aren’t, we will lose assessment altogether. But if that doesn’t happen, there’s an interesting opportunity for technology to become much more central to how students test.

If technology becomes much more widely available in homes and schools, and more central to how students learn, it will accelerate innovation in how we assess. Over time, I see us using technology to test a much broader range of skills and content in an efficient way.

For example, are there ways to develop assessments for skills like creativity, problem-solving and adaptability? Those are super important for college, career and life. But we don’t have great ways of testing them now, and all of them seem to require technology in some way.

Even those critical of traditional assessments are asking whether there are some skills we should be testing in addition to what we do today. It doesn’t have to be either/or. Can technology be a way for us to find efficient means of assessing those things as well? That’s one thing I’m optimistic about.

What do you wish educators and parents better understood about testing?

Educators are more and more savvy about this, but I want parents for sure to understand that while tests matter, they’re not the only thing that matters. They’re not always even the most important thing that matters. It really does depend on at what point a child is in their trajectory and what their child’s goals are.

At the time that they’re trying to get into college, then maybe their college entrance exam is really important. But is a getting-into-kindergarten assessment the most important thing that matters? Maybe not for their child. Tests always should be married to the information they provide and the goal they help you achieve.

Parents and educators also should know that tests are a useful tool for policymakers, principals and superintendents, and district-level and state-level folks. Tests can help them drive the kinds of strategies that we want, such as delivering equity to a school. Tests can provide parents a way to hold those leaders accountable. This is important for parents and teachers to understand.

Holly Kuzmich is executive director of the George W. Bush Institute.

Anne Wicks is the Ann Kimball Johnson Director of the George W. Bush Institute’s Education Reform Initiative.

William McKenzie is senior editorial advisor at the George W. Bush Institute.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)