Barnum: The Growth vs. Proficiency Debate and Why Al Franken Raised a Boring but Critical Issue

Some eyes may have glazed over at Betsy DeVos’s confirmation hearing when Minnesota Sen. Al Franken asked about her views on student growth versus proficiency. The former comedian may have asked the wonkiest question of the night, but his comments are incredibly important for understanding how to judge schools.

Specifically, Franken wanted DeVos to explain her “views on the relative advantage of assessments and using them to measure proficiency or growth.”

DeVos, apparently not understanding the question or the issue Franken raised, stumbled in her answer.

Franken later stated, “I have been an advocate for growth.”

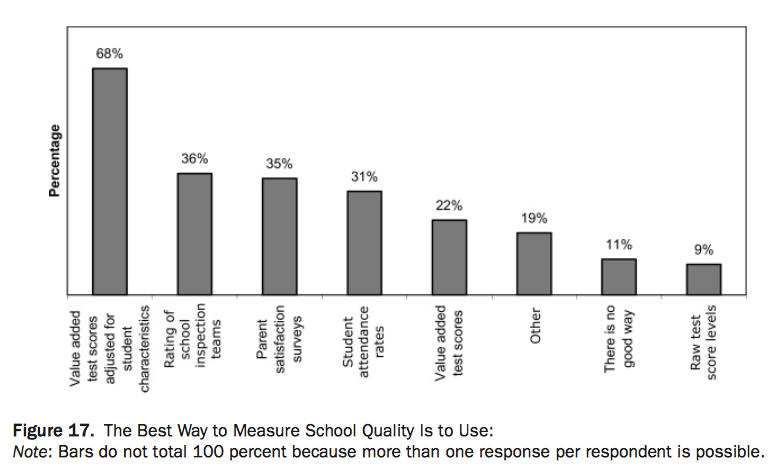

Franken’s position in favor of growth (how much students improve) over proficiency (how many students meet a certain score deemed proficient) appears to be on solid ground. A 2008 survey of education researchers found that more than two in three said that value-added metrics — which examine how much students grow from year to year — are a good way to measure school quality. Just 9 percent said that “raw test scores” — proficiency — made sense for evaluating schools.

Why are researchers, at least in this survey, so in favor of growth measures?

Perhaps the most basic reason is that there are many factors that affect what level a student achieves at and whether they hit the bar set at proficiency. Careful research finds that about 20 percent, and perhaps less, of the variation in student achievement is explained by differences in schools. That pales in comparison to out-of-school factors, like poverty, that have a significant effect on learning. Schools matter, but they aren’t the sole or even main driver of student outcomes.

(Get more research, policy and student growth analysis delivered to your inbox – sign up for The 74 newsletter)

What that means for proficiency is that schools that take disadvantaged students — those in poverty, those who come in at low achievement levels — will look much worse. The school could be doing a great job helping kids improve, but if they start out at a very low level, that might not show up on proficiency measures.

Put simply, proficiency rewards schools for the students they take in, but not necessarily for how they teach students once they’re there.

Proficiency is also problematic not just because it is a score at one point in time — referred to as “status” by researchers — but because it sets an all-or-nothing bar for students to reach. That means it doesn’t matter if a student just missed proficiency or scores way below it.

Franken argues, “With proficiency, teachers ignore the kids at the top who are not going to fall below proficiency, and they ignore the kid at the bottom who they know will never get to proficiency.” Indeed, there is research suggesting this phenomenon — sometimes called “educational triage” — is real, though other studies do not find evidence of it. The extent of such triage likely varies from place to place, but the incentives for it inevitably exist when proficiency is used.

That said, growth measures, particularly for individual teachers, remain controversial. They rely exclusively on test scores, which are limited gauges of school effectiveness, and which usually can’t be created in earlier or later grades. Schools are also not fully in control of how much students improve over time, and such scores for schools and teachers also tend to bounce around from year to year. However, there is evidence that value-added measures are a reasonably accurate gauge of schools’ influence and are predictive of long-run student outcomes.

Meanwhile, judging schools based on a measure that is largely outside of their control, as proficiency would do, can lead to a host of negative consequences.

Most simply, the wrong schools may receive accolades or sanctions. If a school with low proficiency but high growth gets closed down for allegedly poor performance, students are unlikely to benefit. Similarly, schools with high proficiency but low growth may get a pass when they are not, in fact, serving students well.

This is not theoretical. Research in New Orleans found students benefited when struggling schools were closed — but only when such schools were genuinely low-performing as judged by their students’ growth.

Since proficiency scores are highly correlated with poverty, using them to rate schools inevitably means that low-income schools will, by and large, get the worst scores. This may make such schools less desirable places to work, since they face stigma and accountability pressure, potentially driving away good teachers from the schools that need them most. Accountability may be helpful when schools are genuinely struggling, but applying it indiscriminately to high-poverty schools is likely to backfire.

A focus on proficiency may also create the wrong sort of incentives for schools. To the extent schools are able to push out students — and there are certainly examples of this — a heavy focus on proficiency may reward schools for doing just that, since it’s fairly easy to predict which students will hit proficiency each year. In most states, educators or policymakers set the benchmark for proficiency, based on what they believe students should know at that age. Schools may have some sense of which students will grow the most, but they probably can’t predict that with the same degree of certainty.

Proficiency is often the most prominent set of data about a school. Presented without qualification in media reports or on school report cards, such scores can suggest to families that a school is better or worse than it actually is, leading, for instance, many students to compete over attending high-scoring selective enrollment schools, even when they actually have no effect on student outcomes. Proficiency-based measures also may increase the likelihood of school segregation, as affluent families avoid low-income schools, deeming them ineffective based on bad data.

In short, studies suggest that achievement growth measures better capture the effect of schools and avoid the negative side effects of proficiency. Proficiency can provide important information about how students are performing — but very little about how schools are doing.

As states move to implement new accountability systems under the Every Student Succeeds Act, which Betsy DeVos will oversee if she’s confirmed, both state policymakers and the next education secretary should pay careful attention to this research.

—Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)