Back to the Future: GOP Pledge to Abolish Education Department Returns

Republicans have proposed eliminating the federal role in education for decades. But is that even possible?

By Kevin Mahnken | September 26, 2022When former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said in July that her former Cabinet department “should not exist,” it made some waves.

The school choice advocate and Republican mega-donor has kept a relatively low profile since leaving Washington last January, mostly attending to policy developments in her home state of Michigan. Her call to eliminate the U.S. Department of Education, unveiled at a meeting of the right-wing activist group Moms for Liberty, represented a return to the national spotlight — not just for DeVos, but for an idea that has hung around Republican politics for decades.

Even more remarkably, DeVos’s sentiments were echoed a few weeks later by her former boss. Denouncing what he described as the politicized teaching of subjects like race and sexuality before a joyful crowd at the Conservative Political Action Conference, President Trump vowed that if the federal government promoted “radicalism” in academic instruction, “we should abolish the Department of Education.”

Conservatives have sought to scrap the department, and dramatically reduce Washington’s K-12 footprint, since it was created in 1979. Those efforts, including a one-sentence bill that would take effect by the end of this year, have generally been seen as quixotic; even when they held unified control over Congress and the White House, Trump and DeVos floated, but never came close to pursuing, a plan to merge the Departments of Education and Labor.

The political fallout of that kind of reshuffle would be hard to predict, but potentially severe. According to a 2018 Pew poll, over half of Americans view the Department of Education favorably. The department collects and disseminates scientific evidence on schooling through the Institute of Education Sciences, plays a public watchdog role through its Office of Civil Rights, and helps equalize school funding with the tens of billions of dollars provided by Title I. All of these purposes are served with the smallest workforce of any cabinet department.

But while policy experts consider outright abolition a farfetched notion, they say it reflects a long-running contest between dueling urges in American education: a strong distrust of federal influence on one hand, and on the other, profound dissatisfaction with the status quo. During the presidencies of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, the second impulse was dominant, with massive new federal initiatives launched around school performance and accountability. But resistance to federal authority has been growing for a decade, and the renewed energy around abolition is breaking through just as the disgust of Republican voters — with perceived indoctrination in classrooms, federal recommendations on COVID safety, and much else — has crested.

Kevin Kosar, a senior fellow at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute who studies public administration, said that the government’s response to COVID had engendered “a clear backlash” among Republicans. Even as pandemic health measures were largely decided at the state level, he added, Washington’s guidelines on masking and vaccines in schools have fueled the party’s enmity toward federal interventions in education.

“The Right certainly doesn’t trust the federal government to lead some sort of learning recovery response,” Kosar said. “They would much rather pull the power back to local communities and have the feds stay as far away as possible.”

Jack Jennings, a retired policy maven who served as the Democrats’ top education aide in the House of Representatives, argued that shrinking the public sector is never as easy as it sounds. But he added that abolition is electorally potent with the Republican base before the 2022 midterm elections, likening it to a “red flag in front of a bull.”

“It’s not an issue that’s going to come to fruition soon, but it’s one of those things that rattles the cages of conservatives,” Jennings said.

Unions divided

The department has always had its share of detractors. At its inception, that group even included many Democrats.

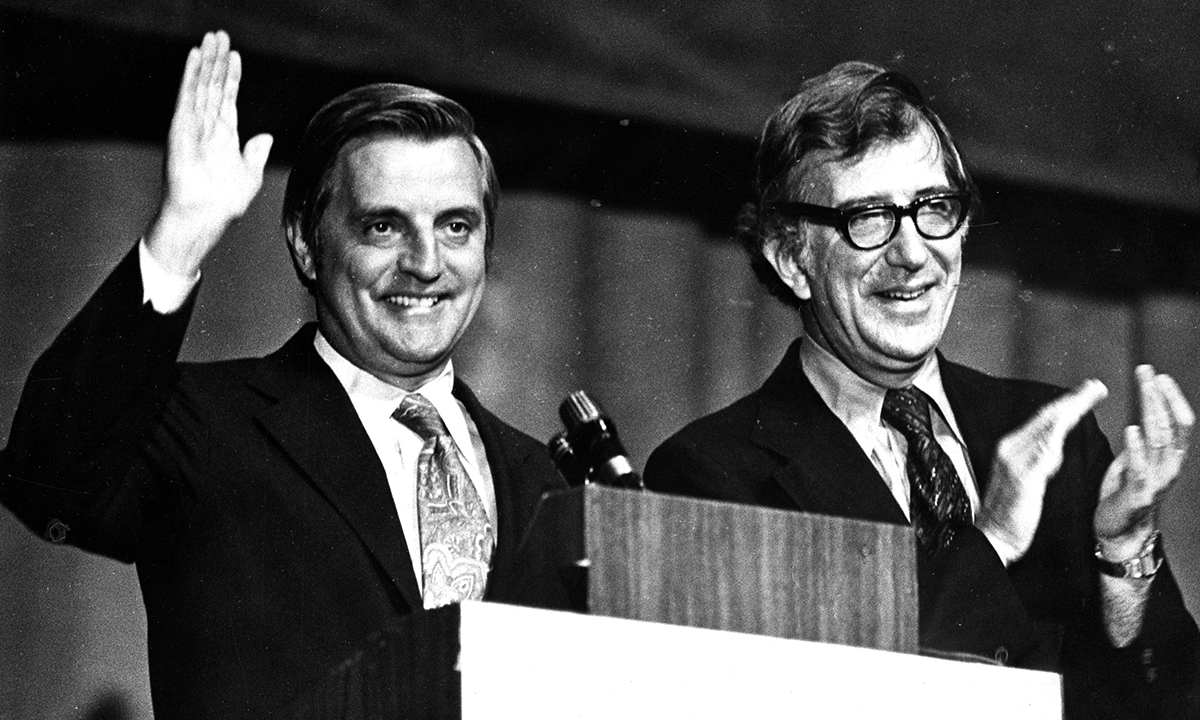

By the late 1970s, the federal government’s responsibilities over education — codified in landmark laws like the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 — were housed in the then-Department of Healthcare, Education, and Welfare. President Jimmy Carter’s insistence on carving out an entity devoted specifically to K-12 was borne of a commitment made to the National Education Agency, the nation’s largest teachers’ union, which had helped Carter secure the Democratic nomination in 1976. Until that election, the NEA had never issued a presidential endorsement.

But according to Jennings, many in the president’s own party were leery of the idea. Even fervent liberals worried that a dedicated agency would induce untold “meddling” in the affairs of schools and districts. Albert Shanker, the influential president of the American Federation of Teachers, lobbied against the change out of concern that his own union would be put at a disadvantage.

“[Carter] was fulfilling a campaign promise by sending it to the Congress,” Jennings recalled. “But when the Congress received it, Democrats were not all in favor of it.”

In the end, necessary authorizing legislation passed in the perennially Democratic House by just four votes. But Democratic resistance faded over time, as the government’s sizable outlays to educate poor and disabled students gelled easily with the party’s own priorities. Hostility among Republicans would be a feature of the policy landscape for years to come.

Ronald Reagan began campaigning to unwind the newly created department while still a presidential candidate. That pledge was only abandoned years later, following the national alarm stoked by the release of the administration’s bombshell report, A Nation at Risk; after declaring a national education emergency in its first term, it would have appeared perverse for the administration to gut the nation’s foremost education authority in its second.

Still, Reagan later appointed as education secretary the public intellectual William Bennett, whose views were thought to mirror his own. And the Republican position remained clear for years afterward. Lamar Alexander, a former Tennessee governor who led the department under President George H.W. Bush and later served three terms in the U.S. Senate, worked abolition into his abortive 1996 presidential campaign. The party platform that year for eventual nominee Bob Dole included a promise to eliminate the Department of Education (along with the Departments of Energy, Commerce, and Housing and Urban Development).

David Cleary, a former senior aide to Alexander who now serves as the Republican staff director for the Senate’s Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, said his party’s enduring skepticism toward federal overreach explained its drive to abolish. Moreover, few of the department’s functions need to be administered nationally.

“The U.S. Department of Education doesn’t establish a curriculum — thank God — doesn’t establish education standards, doesn’t establish tests, and doesn’t establish criteria for institutions of higher education,” Cleary said. “So it really is just a grant-making entity with a huge bureaucracy.”

A short-lived honeymoon

Notwithstanding the Right’s philosophical objections, however, the last quarter-century has been a time of bipartisan acceptance for the department. The key figure in that detente was George W. Bush.

It was the Texas governor’s wholesale embrace of education reform — part of a “compassionate conservative” push that helped Republicans recover from Dole’s landslide 1996 defeat — that set the stage for the No Child Left Behind Act. That law, the biggest expansion of the federal government’s educational powers since the Civil Rights era, was enacted through a generational compromise with Democrats: The Left would get more resources to improve chronically failing schools (which they later complained was short-changed), while the Right would get tighter accountability for academic results (which later trampled on local autonomy, they grumbled).

Both parties returned early from their political honeymoon, with Democrats and teachers’ unions striking most of the early blows against a law they helped shepherd into being. But it was Republicans, disenchanted with the department’s broader scope over local schools, that migrated further from the vision of a more muscular federal role.

Their distaste only grew as responsibility for implementing NCLB fell to the Obama administration. As Secretary of Education Arne Duncan backed ambitious policy initiatives like Race to the Top and Common Core, Tea Party conservatives — increasingly in concert with the leadership of both NEA and AFT — demanded a reversal of the department’s growing remit.

Chester Finn, a senior fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution and president emeritus of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, compared the public’s attitude toward education reform to a pendulum that periodically swings toward greater federal involvement.

“But then we suddenly discover that that’s too pushy…and it’s embarrassing people, so there’s a backlash,” Finn remarked. “That’s what was beginning to happen in the late Bush and Obama years, and that’s when they started giving waivers and making exceptions so that the pushing wasn’t as hard or as uniform.”

The retreat from NCLB’s strictures in the mid-2010s was not total. The law that supplanted it, 2015’s Every Student Succeeds Act, left in place some Bush- and Obama-era accountability measures while granting states more freedom to chart their own course. But even the relaxation of regulations couldn’t shield the department from the dissatisfaction that would follow in the pandemic era.

“It still felt like there was a truce, fundamentally — that the federal role in education was legit,” said AEI’s Kosar. “Then we get some of the executive orders in the Obama administration that struck the right as ‘woke.’ And now we get schools being an epicenter for debates about how to respond to the coronavirus. That’s what sparked the most recent revolt against the feds.”

‘Anyone pushing this is going to be savaged’

If the intellectual history of abolition is well-documented, its potential as a governing proposal is hazy.

To put it simply, the Department of Education is a well-known entity with countless supportive constituencies. Eliminating its offices and employees would require relocating the trillion-dollar federal student loan program, which plays an integral role in sending millions of students to college. Title I, which dispenses billions to districts and schools that serve children facing academic and socioeconomic challenges, has its own army of defenders in both Congress and the states. Billions more go to special-education students.

“It’s going to be a heavy lift,” Kosar said. “Every interest group is going to come out and want to keep its programs alive. And of course, anyone pushing to do this is going to be savaged viciously as anti-education.”

Even if a future Republican administration were to keep the most popular initiatives intact, they would face two significant logistical hurdles. First, relocating those programs in other agencies — student loans at the Treasury, for instance, or the Office of Civil Rights at the Justice Department — would almost certainly require a statutory change that Democrats wouldn’t go along with. So full GOP control of government, plus filibuster-proof majorities, would be a necessity.

If this could be achieved, the federal role, however shrunken, would be scattered in pieces across the executive branch. Without the unified leadership provided by a secretary, their effectiveness could be severely hampered.

Jennings, the former longtime House staffer, said the end result would be a succession of functions “spun off into different areas of the federal government. And there would be no coordination among them because they would be answerable to different people.”

Cleary, the Senate HELP Committee aide, conceded that the political obstacles would be significant. But a more limited administrative campaign against the department, entailing the systematic elimination of Democratic regulations and mass block-granting of its various programs, could be achieved under a future Republican administration, he said.

“If I were the secretary of education, or advising one, I would do a hiring freeze and just not hire new people, and start to burn out the Deep State, if you will,” he said. “You don’t really need as many people as they have.”

Finn, a former department hand who openly desires a “serious rethinking” of the federal role in education, said that neither wholesale elimination nor reform was likely on any near-term timeframe. Entering an era of greater partisan divides on the Department of Education, he added, Republicans would be forced to offer greater specificity around their signature education promise.

“The question’s always the same: Do [conservatives] just want to abolish the building with the name over it that says ‘Department of Education?’ Or do they want to abolish the federal functions that it contains? Because those are such different things.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter