At Center of MI Election, a School Choice Measure Few Residents Have Heard About

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and GOP challenger Tudor Dixon differ sharply on measure that could create one of the largest voucher-like systems in the U.S.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated Nov. 9

A proposal that would have made Michigan home to one of the largest voucher-like systems in the country is in jeopardy after the victory Tuesday night of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the likely emergence of a Democratic state legislature.

Whitmer handily defeated Trump-endorsed Republican Tudor Dixon. But it is the possibility of Michigan’s first Democratic “trifecta” since 1984 that could kill the proposal to create Education Savings Accounts in the state. Even if voters collected enough signatures to put the matter to a vote in the legislature, Democrats would almost certainly reject it, experts say.

A proposal before Michigan voters would create one of the largest voucher-like systems in the country, with the potential to offer more than a half-billion dollars in public funds for students to attend private schools.

There’s just one hitch: Most residents have never heard of it.

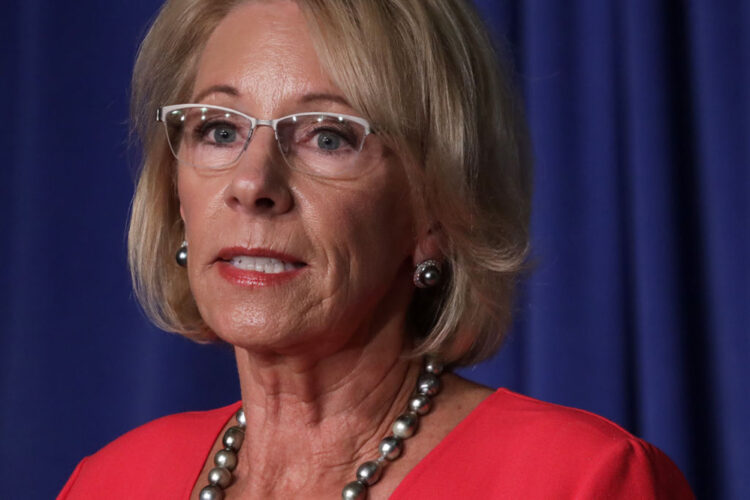

In a recent statewide poll, 93% of the electorate knew little or nothing about the proposal, which has been enthusiastically backed by former education secretary Betsy DeVos and her family, who have donated $4 million to the cause. The proposal would create Education Scholarship Accounts (ESAs) that offer 100 percent tax credit for donations to “opportunity scholarships” that pay for private school tuition and other educational services.

“There’s always conversations about vouchers,” said Terah Chambers of East Lansing. “But I haven’t heard anything from parents or others in my district about this initiative.”

Chambers serves on the board of her local school district, where her son is in sixth grade. She is also a professor of education, focusing on K-12 administration, at Michigan State University. If anyone would be expected to understand the complexities of the state’s proposed school choice initiative — or hear other parents’ concerns — it would be her.

But that’s not the case.

“I’m an education policy scholar and I don’t always understand the nuances of these types of initiatives,” she said. “They can be intentionally written in a way that masks the motivation and impact. Of course people will have trouble understanding them.”

Michigan has long debated vouchers and school choice. So far, legal efforts to overturn a constitutional amendment barring public funds from going to private schools have failed. In 2000, the state emphatically defeated a voucher initiative. But there’s some evidence that the times have changed as the pandemic exacerbated existing educational inequities and fueled parent discontent. In addition, the U.S. Supreme Court has in recent years shown itself willing to embrace broad definitions of school choice.

Along with the funds from DeVos and her family, “Let MI Kids Learn” — the political action committee backing the initiative — has received another $4 million from other supporters.

But few potential voters are focused on the measure.

A May survey conducted by EPIC-MRA, a Michigan-based polling company, found that 93 percent of Michigan voters knew little or nothing about the proposal. After respondents heard a neutral message explaining the initiative, 36 percent supported it and 48 percent opposed it, with 16 percent undecided. That reflects a majority of Democrats and plurality of Republicans, said Bernie Porn, the company’s president.

The lack of attention is in inverse proportion to the proposal’s possible outsized impact. It would create one of the largest ESA programs in the country in terms of how much money it can divert from the state, according to Josh Cowen, a professor of education policy at Michigan State University.

The scholarship fund has a $500 million cap the first year, and could increase by 20 percent annually depending on how much of the fund is distributed.

‘Tax shelters for the wealthy’

Michigan’s scholarship proposal is modeled on one passed in Kentucky, said Beth DeShone, executive director of the Great Lakes Education Project, an advocacy group established by DeVos. The Kentucky program is currently being challenged in court. The Franklin District Court ruled that the program violated a provision in the state constitution that prohibits using private money for public education. The decision was appealed, and the state’s Supreme Court heard arguments in October.

This type of initiative “is distinctly different than a state voucher that is normally given directly to a private school,” DeShone added. “Here, the families completely control where those dollars go and who the service provider will be. We fully believe that families need every opportunity in their toolbox to meet the needs of their individual students.”

The Michigan scholarships would be available to all students five years old or over whose family is defined as low-income under the proposal’s formula, has a disability or is in foster care. The money is expected to primarily fund private school tuition, but can also be used for tutoring, transportation and other education needs, according to Michael Van Beek, director of research at the conservative Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a Michigan think tank.

Education choice has also been a hot topic in the Michigan governor’s race. Democratic incumbent Gretchen Whitmer opposes the education proposal, while her Republican challenger Tudor Dixon supports it. DeVos is also a big Dixon supporter and has contributed at least $7 million to her campaign.

Last year, both houses of the Michigan legislature passed bills that would have created ESAs, but Whitmer vetoed them, saying they would “turn private schools into tax shelters for the wealthy.”

In most other states, that would be the end of the story: Advocates would have to wait for a more sympathetic governor or put it before voters in 2024. But in Michigan, supporters have another option: Residents can petition to send the matter to the legislature. They have already turned in the needed number of signatures (8 percent of those who voted in the last gubernatorial election — in this case, 340,047 signatures) and once they are certified by the secretary of state, the proposal will go before the legislature.

If it passes, the governor cannot veto it. If it is defeated or not acted upon, it will go before voters in 2024.

The idea was that the Republican-dominated legislature would “rubber stamp” the initiative, said Bill Ballenger, a political pundit who served as a Republican state legislator almost 50 years ago and now publishes The Ballenger Report, an irreverent look at Michigan politics. “It would be an end-run around the governor.”

But he predicted Benson will not submit the initiative to the legislature until after the Nov. 8 election.

And since an independent commission redrew the state’s districts, “everything is up for grabs,” Ballenger said. “There is rampant speculation about whether the Republicans will control one or both of the Houses or if the Democrats will.” And while Whitmer is still ahead of Dixon in most polls, her lead is shrinking as the election nears.

Ballenger, noting the 2000 private-school voucher initiative that “got killed,” nonetheless wonders if “the pandemic has shifted public opinion.” But he still believes the measure will be defeated if it goes on the ballot in 2024.

‘Money should follow the child’

Unlike most potential voters in the state, Katie Woodhams, a mother of three in the Kalamazoo area, is well-aware of the opportunity scholarships and is a big supporter.

Her oldest, a high school freshman, has high-functioning autism and does most of his schooling remotely. But he participates in archery on-site. He can also meet with teachers at school or, if room is available, sit in on a class.

Her middle son is attending seventh grade in-class in a public school, but was previously enrolled in virtual learning because of severe asthma. And her daughter, a first-grader, is also going virtual for the time being.

The schooling is provided without cost through the public system, and she believes her children have received “a great education.” She’s become a strong advocate for choice, she said, because that’s what her children have enjoyed.

“It’s extremely important we are funding the students and not funding systems,” she said, echoing a common message among supporters.

She’d also like financial help, which the act could give, to provide sports for her middle son, arts programs for her daughter and social coaching for her older son; Woodhams said she and her husband now pay $150 monthly for the social skills coaching.

Part of the trouble are widely conflicting estimates about how the tax credits — which allow residents to divert state taxes to the scholarships — will affect spending on public education. Much of that depends on how many students now going to public schools would use scholarships to switch to private schools.

Based on research conducted by the nonprofit EdChoice, 60-90 percent of scholarship uses would come from public schools, Van Beek, of the Mackinac Center, said. The financial impact on the state would be minimal, because what it would lose in taxes, it would gain by not paying for students who have left public education, he added.

Cowen, who has researched voucher programs around the country for 17 years — including five as an official evaluator of Wisconsin’s voucher program —noted that both Arizona and New Hampshire recently expanded private school voucher programs. In Arizona, 75 percent of the new voucher users were students already in private schools and in New Hampshire, that figure was 90 percent.

“Don’t take my word for it, don’t take Mackinac’s word, look what happened in other states,” he said.

Peeling back the layers

The main group opposing the initiative, the For MI Kids, For Our Schools coalition, has raised far less money than its opposition — the majority from the Michigan’s teachers union PAC. Mark Schauer, treasurer of the opposition coalition, argues that the program has “the potential to siphon up to $1 billion in public tax dollars away from the state.”

Chambers, the school board member and education professor, worries that the proposal “is a mechanism to put public funds into private hands. The trouble with initiatives like this is that they sound great on paper — who wants to oppose the idea of opportunity scholarships — but if you peel back the layers, this will not help us accomplish what we want to in this state.”

Despite a very favorable education budget passed by the state last year, Chambers said the state is facing “a long-time disinvestment in education that is cumulative.” She pointed to the fact the state ranked 36th in the recent National Assessment of Educational Progress released in October.

One thing that is often lost in school choice debates, Cowen said, is how students do academically. Research, especially more recent studies, shows that children who use vouchers to move to private schools often do worse academically based on standardized test scores than comparable students in public schools. That’s because there simply aren’t enough good private schools to serve at-risk students, he said.

For Bernita Bradley, a Detroit resident and a director with the National Parents Union, a network of parent organizations and activists, neither side is looking out for the interests of Black and brown children.

She has tried city and suburban public, charter and private schools for her children and wasn’t satisfied with any of them. She agrees with Republicans that “money should follow the child,” but asks, “Who’s going to make sure that’s equitably done?”

For that reason, she practices what she calls “extreme choice.” In 2020, she started Engaged Detroit, a homeschooling co-op and advocacy network. She homeschooled her own daughter, who has now graduated, for a year and a half.

Lack of satisfactory educational opportunities for many of Michigan’s children “is not a pandemic thing, or a last 10- or 20-years thing,” she said. “This has been going on for generations.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)