As Educators Across America Demand Better Pay and Greater Education Spending, Delaware Has a Novel Proposal: Money to Help Teachers With Their Student Loans

Rebecca Slimbock has always wanted to be a teacher, and she never expected it to be easy. But more than three years into her career, she did not think she would still be living with her parents and devoting half her monthly income toward the approximately $100,000 she owes in student loans.

Slimbock, 26, teaches third grade at Kuumba Academy, a charter school in Wilmington, Delaware, that serves mostly children of color from low-income families.

“My passion is in urban education,” she said.

But now she’s looking to take her talents to a higher-paying urban district in a neighboring state, such as in Chester, Pennsylvania, or Camden, New Jersey — both less than an hour’s drive away. The main reason she wants to leave is pay.

In an attempt to recruit new teachers and keep educators like Slimbock in Delaware, a bill proposed in March would allow the state to pay up to $2,000 per year in loan forgiveness for up to five years for some teachers. To receive assistance under the proposed bill, teachers have to be rated “effective,” which a majority of teachers typically are. The bill is aimed at those who teach in schools primarily serving low-income students or students learning English, special education teachers, and teachers who work in high-need subject areas, such as STEM and foreign languages. Delaware’s House education committee approved the bill, and it is currently awaiting a hearing in the appropriations committee.

But is it enough?

Slimbock, who has a master’s degree from Widener University and is a certified reading specialist, knew being a teacher wouldn’t be a path to the 1 percent, but she didn’t think she would worry so much about paying off her debt, especially after earning an advanced degree. An additional $2,000 isn’t enough to change her mind about leaving the state. For her, that would be just two months of loan payments a year.

“I did go into this field knowing that it can be a little hard,” Slimbock said. “But this feels very hard. This feels almost impossible.”

While her salary of less than $50,000 might go further for teachers in some states, Delaware’s cost of living is higher — and she has the crushing burden of more than $20,000 a year in student loan payments. To live near her school in Wilmington, Slimbock would need about $1,200 per month to meet the average rent of one-bedroom apartments there, according to Zillow data.

Average teacher salary in Delaware was $60,214 in 2017, according to an analysis by the National Education Association. Average teacher salaries in nearby Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania were all more than $5,000 higher that year, though the cost of living is similar.

The bill is “one piece of a puzzle” in the effort to recruit and retain teachers, said Shana Payne, director of the Office of Higher Education within the Delaware Department of Education.

“It gives schools one more thing in their toolbox to be able to either recruit or encourage” teachers to stay in the classroom, she told The 74.

Although they acknowledged that the bill is a good first step, experts said forgiving up to $2,000 in loans annually may not be enough to draw people into the teaching profession or keep them at high-needs schools. Average student loan debt nationally was about $30,100 per borrower in 2015, when about 70 percent of students were graduating with debt. That number often climbs even higher for teachers, who frequently pay out of pocket or take out loans for additional degrees and certifications after they graduate and start teaching. Federal loan forgiveness programs for teachers are complex, and a recent NPR investigation revealed a pattern of teachers having federal grants turned into loans without warning. Additionally, teacher pay lags behind that of similarly educated workers, making the burden heavier.

Elizabeth Farley-Ripple, a professor at the University of Delaware School of Education, said the state is facing an impending teacher shortage but predicted the bill would likely not be enough to entice new people into the profession.

“I totally think that this bill is in the right vein; I think it’s drawing attention to an important issue that the state needs to address,” Farley-Ripple said. But she’s hesitant to praise the proposal too much, as she thinks it needs to have “more weight behind it” to make a considerable financial impact for teachers.

Lawsuit highlights vulnerabilities

The proposed legislation, which would benefit teachers in schools serving mostly low-income students, comes as the state is dealing with a lawsuit alleging it is failing to adequately educate many of the same groups taught by those who could benefit from the program. The suit points to test scores as evidence that achievement gaps exist among groups of students in the state, with many students achieving “far below” standards set by Delaware’s Department of Education.

The suit argues that schools with high concentrations of vulnerable students lack qualified, specially trained teachers and other resources they need. It alleges that the state’s funding formula and governance system are unjust, especially in Wilmington, its largest city.

A report released in 2015 revealed that Delaware schools with high concentrations of students living in poverty have a 20 percent turnover rate for teachers, almost double the state average of 11 percent. About 39 percent of teachers leaving high-poverty schools move to schools where students are more affluent, according to the report.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Delaware filed the suit against the state on behalf of the local NAACP and a citizen group called Delawareans for Educational Opportunity. A spokesperson for the Delaware Department of Education declined to comment on the ongoing litigation.

A national problem

Like teachers around the country staging walkouts and strikes, teachers in Delaware are frustrated by low pay and what they see as a lack of investment in their schools. Though they are not considering a strike, educators there say they empathize with their colleagues in other states who have protested.

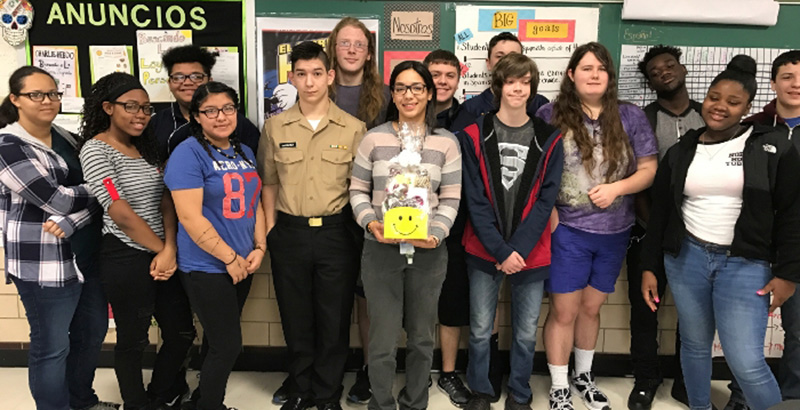

Pati Candelario, 27, teaches Spanish at Seaford High School in one of the state’s rural southern districts. To supplement her income from teaching, Candelario coaches basketball, homeschools students who cannot attend traditional schools (such as those who have given birth or gotten into violent fights), and has also worked for a summer camp. Pay is one of several reasons Candelario has decided this will be her last year in the classroom. She plans to start law school in the fall.

Candelario, who is also the union representative at her school, said she can empathize with teachers around the country who have walked off the job.

“Teachers are required to do an absurd amount of things for not a lot of pay,” in addition to dealing with intense and sometimes dangerous situations in the classroom, Candelario said.

She gets by, but Candelario said it would be much more difficult to manage her low pay and long hours if she had children. She recently had to spend the $1,000 she saved for her upcoming wedding when she got into a car accident.

“Teaching … shouldn’t be this way,” she said. “I can’t even really prepare for a rainy day.”

Slimbock said several teachers on the Kuumba staff are thinking of leaving for higher-paying jobs, but teacher turnover isn’t the only challenge. As in many schools with high concentrations of students in poverty, teachers are filling gaps left by missing social workers, school nurses, and counselors. Teachers get burned out trying to do so much, she said.

“There is something special about what teachers in these areas do,” she said, including serving students struggling with poverty, hunger, trauma, language barriers, and other challenges. “And I just don’t feel like $2,000 is enough … to keep us there, unfortunately.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)