Antonucci: Chicago Teachers Walkout Calls the Questions — What Does ‘Safe’ Mean, and Who Gets to Decide?

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears most Wednesdays; see the full archive.

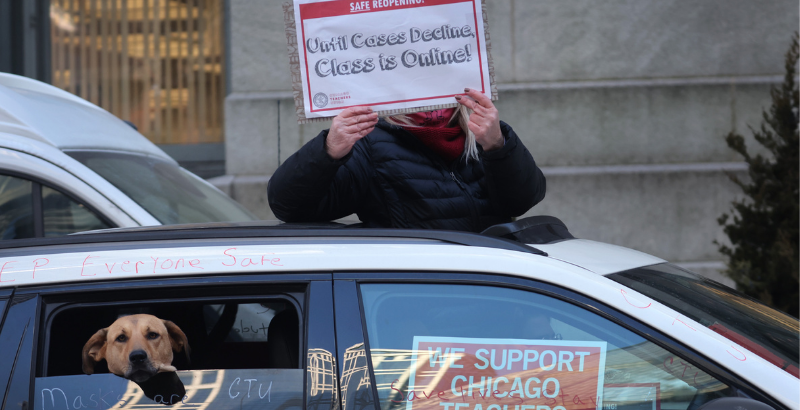

The Chicago Teachers Union decided last week to cease in-person schooling until a variety of conditions were met. In response, Chicago Public Schools refused to allow teachers to log in for remote instruction and demanded they return to the classroom. After days of negotiations, the two sides reached a tentative agreement. In-person classes resumed Jan. 12.

In the interim, familiar debates reappeared. The union claimed the surge in infections and inadequate COVID testing made the schools unsafe. The district and the mayor said the danger to children was still very low, and that measures taken made the schools safer than other indoor spaces.

“We’d rather be in our classes teaching, we’d rather have the schools open. What we are saying though is that right now we’re in the middle of a major surge, it is breaking all the records and hospitals are full,” said union President Jesse Sharkey on Jan. 5.

“Across the whole city — approximately 550,000 children — we are averaging just seven COVID hospitalizations a day right now for children ages 0 to 17,” said Chicago Health Commissioner Allison Arwady. “I want to just reassure you, especially if you are vaccinated, if your child is vaccinated, this is behaving like the flu, and we don’t close school districts for an extended amount of time because of the flu.”

When talking about safety, particularly the safety of children, people get very heated. Both sides cited “data” and “science,” but people actually decide what’s safe based on their perceptions. Chicago Public Schools reported that 82 percent of teachers showed up for work Jan. 3, but on Jan. 5 they were all out on strike. On Jan. 11, they all returned. Did the data change that drastically, or did teachers’ feelings about their safety shift during the last week?

Individual parents and teachers decide for themselves whether their school is safe. There is no compelling reason to enter a school building if you legitimately believe your life is in danger. But that’s not what caused the problem in Chicago and elsewhere. It’s when you have to decide if it’s safe for anyone else to enter the building.

These are very difficult decisions to make during a pandemic, and we elect and appoint public officials to make them, while reserving the right to decide what’s best for ourselves as individuals. Where the union went very wrong was in taking that choice away from Chicago’s parents and citizens.

The Chicago Teachers Union held a meeting of its delegates on the afternoon of Jan. 4. The delegates “overwhelmingly” approved sending to the rank-and-file a vote on whether to refuse to perform in-person instruction, which would require a two-thirds majority to pass. The vote was held online that very evening and the results announced just before 9 p.m. — 73 percent approved of a work stoppage.

But it wasn’t 73 percent of Chicagoans affected. Or 73 percent of school employees. Or 73 percent of teachers. Or even 73 percent of union members. It was 73 percent of those members who managed to get online and cast a vote with just a few hours notice, and the union did not release turnout figures.

But it was enough to shut down the city’s public school system.

Whether strikes are legal in a particular place or not, workers always have the ability to withhold their labor. Mayor Lori Lightfoot and district officials declared the schools open last week, but without enough teachers, they closed them. Even if they got a court order, how could it possibly be enforced? Who is going to fire 20,000 teachers, and how would that improve anything?

So the mayor had no choice but to work out the best deal possible to get schools reopened. That’s what happened. But what happens next?

The union released its proposal over the weekend, and it covered testing, masking, positivity rates, etc. Those items were contentious, but not any more so than demands made in past Chicago labor disputes. There is an important provision, however, that doesn’t seem to have been entirely settled. It’s the one thing that makes public school teacher strikes different from almost any other walkout: makeup days.

Since teachers don’t work every weekday for a full calendar year, losses of workdays can be restored later, and virtually every settlement includes a provision that strike days are restored so teachers won’t lose any pay. This proposal was no different, calling on Chicago schools to “make up any canceled instructional days, and no bargaining unit employee who was locked out or participated in the remote work action shall suffer any discipline or loss of pay.”

Lightfoot vehemently insisted she would not compensate teachers for the stoppage. “We will not pay you to abandon your posts and your children at a time when they and their families need us most,” she said. “It will not happen on my watch.”

She made similar statements during the 11-day strike in 2019, but ultimately had to restore five of the 11 days to get an agreement. This week, the pay schedule made it impossible for her to employ any immediate leverage. Chicago teachers are paid every two weeks, but it’s for the previous two weeks’ work. They will receive a full paycheck Jan. 14, which covers the final two weeks of December. The strike could have gone on until Jan. 28 before teachers would have missed any pay.

Whether pay will be withheld this time, or if the days will be made up, is to be left to Chicago Public Schools CEO Pedro Martinez, according to a report in Chalkbeat Chicago.

Some have suggested that pressure was brought to bear on the union from Democratic politicians and the White House, concerned that continued school closures will adversely affect them in the 2022 midterm elections. Whatever their motivations, they have been unequivocal in their support for in-person instruction.

“The president couldn’t be clearer — schools in this country should remain open,” said White House pandemic response team coordinator Jeff Zients.

“Long story short, we want schools to be open, the president wants them to be open and we’re going to continue to use every resource and work to ensure that’s the case,” said White House press secretary Jen Psaki.

“We’ve been very clear, our expectation is for schools to be open full-time for students for in-person learning,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona.

And Dr. Rochelle Walensky, head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said her agency’s guidelines “provide the tools necessary to get the schools reopened for in-person learning and to keep them open for the rest of the school year.”

But don’t overestimate their influence. The Chicago Teachers Union, like most large affiliates of the American Federation of Teachers, is its own domain, which cannot be overruled by AFT President Randi Weingarten, never mind Cardona. It is also run by officers who are considerably further to the left politically than your standard Democratic officeholder.

Schools have been closed, and are still being closed, in many places due to COVID transmission, but shutdowns of entire districts due to union strikes and work actions will be few and far between. When they do take place, as in Chicago, they will be settled — for better or worse — by the same collective bargaining methods deployed in previous labor stoppages. And don’t assume Chicago’s labor troubles are over.

“This agreement is only a modicum of safety,” said Stacy Davis Gates, the union’s vice president.

That may be frustrating to those who are only now becoming aware of the K-12 public education world we have created, but there it is.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)