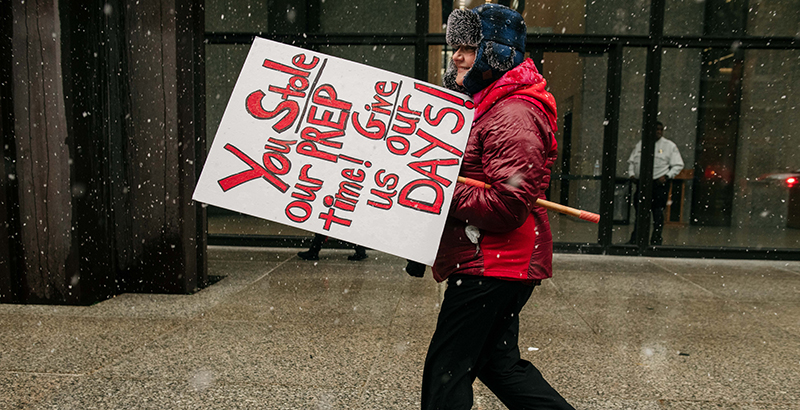

Union Report: A Look at the Before-and-After of the Chicago Teacher Strike Raises the Question — Was the Walkout Worth It?

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears most Wednesdays; see the full archive.

The Chicago Teachers Union agreed to suspend its strike and accept a tentative agreement after 11 school days on the picket line. The agreement was held up for a day by the union’s insistence that the days on strike be restored to the school calendar — so members would be paid for the time they lost during the walkout. The union’s 24,000 members have 10 days from the date the strike was suspended to mull over the deal before voting at school sites all over the city.

Here is a CTU bargaining summary dated Oct. 29 that spells out the progress of negotiations up until that point. It is a useful timeline showing where things stood before and during the strike. (Click here for a larger view)

Bargaining Summary 10 29 19 (Text)

The union lauded the “landmark” agreement and listed a number of positive provisions that had been won in negotiations, most of which involved increased staffing. It was less forthcoming about the areas where it made little or no progress. These were considerable.

Salaries. The original offer by Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Chicago Public Schools was for a 14 percent increase over five years. The union wanted 15 percent over three years. In August, an independent fact-finder recommended a 16 percent hike over five years, to which Lightfoot immediately agreed. The union immediately rejected the offer.

CTU ultimately accepted the fact-finder’s recommendation.

Health insurance. The district had unilaterally raised premiums by 0.8 percent earlier this year, but the union filed an unfair labor practice complaint. Under the agreement, the district rescinded the increase and the union rescinded the complaint. Otherwise, the fact-finder’s recommendation for premiums was accepted by both sides: no increases for the first three years, a quarter-percent increase in the fourth year and a half-percent increase in the fifth year.

Term of contract. The union insisted on a three-year deal, which would have meant negotiations on the next contract would have begun before the next mayoral election. Lightfoot insisted on a five-year deal. The union said it would bend only if Lightfoot would ask the state legislature to repeal the 1995 Amendatory Act (which limited the scope of collective bargaining) and restore an elected school board. She refused, but the union relented anyway after speaking with the governor and legislative leaders about the issue. The tentative agreement is for five years.

Elementary prep time. The union’s bargaining team demanded 30 minutes. They got zero.

Class size limits. Unchanged, except that if they are exceeded, a teacher may appeal for a remedy to a newly constituted Joint Class Size Assessment Council, consisting of six members appointed by the district and six by the union. The council will determine if, and what, action is to be taken. If class size limits are greatly exceeded, the council will act automatically, without waiting for a teacher request.

Staffing. CTU emphasized this issue in all public statements. The union won 209 additional social workers and 250 additional nurses over the duration of the contract. The district will also hire additional case managers according to a formula based on the number of students with individualized education programs.

In the short term, this means an additional 44 social workers and 55 nurses next year above what the district had already budgeted. Chicago has more than 600 schools.

As for school psychologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech language pathologists and audiologists, the district simply agreed to reduce the ratio of students to each of these professions by an unspecified amount. Considering that enrollment in Chicago Public Schools is falling, this can be achieved simply by not laying off anyone.

School closings. The previous contract contained a side agreement with a moratorium on school closings. That was not renewed.

The agreement to limit the number of charter schools was renewed, but the word “moratorium” was deleted and replaced with “net zero increase” in the number of charter schools.

In addition to the above provisions, there were a number of items of primary interest to the union itself, and not so much to its members.

● The union can now review and provide input on district capital expenditures.

● The school board must provide the union monthly (weekly during August, September and October) contact information for all employees, including phone numbers (cell included) and email addresses (personal included). The information must include whether the employee is a dues-paying member and contributing via payroll deduction to the union’s political action committee. Additionally, the board must provide the union with notice of all meetings of 25 or more new employees and allow the union space for an information table at district staff centers.

● The contract increases the number of CTU members released for full-time union work from 45 to 50, and includes those elected to municipal, county, state or federal office. They will be unpaid by the district but will continue to accrue employee health and pension benefits at their own expense, and will maintain their seniority.

● Staffing was a priority issue for the union, but CTU won a provision that reduces the pool of librarians and teacher support positions. To ensure those will be union jobs, the contract stipulates that the district will not “contract out or otherwise privatize” those positions and will reduce to the point of elimination all contract or agency nurses.

Despite these mixed results, CTU President Jesse Sharkey emphasized to the union’s house of delegates that there were no “givebacks” in this contract, implying there had been in previous contracts. He said the 2012 strike was a defensive job action that resulted in some losses.

Sharkey’s reinterpretation of the contract achieved after the “historic” 2012 strike continues.

The relatively slim margin (362-242) by which the CTU delegates accepted the 2019 agreement and sent it to the rank-and-file members for ratification highlights the skepticism they felt about the results. Economic considerations certainly pushed the affirmative vote over the top, which is why the demand to make up the strike days became a sticking point. Lost pay would have amounted to almost the entire first two years of increases in the new contract.

But staying out was only making the problem worse. If the union had remained out for a week, or a month, in a dispute over strike days, then an additional week, or month, would have to be restored, running the school year well into the summer. Ultimately, Lightfoot agreed to restore five of the 11 days, but even this compromise came with an asterisk.

All Illinois school districts are required by state law to provide 176 days of instruction. If they don’t, they lose state funding for the missed days. In order to maintain full funding, Lightfoot had to restore at least three days.

The teachers were also up against the expiration of their health benefits. On Nov. 1, they would have been shuttled over to COBRA, which would have continued their coverage but with the full cost being paid by the teacher.

The strike is over. The question is not whether teachers came out ahead; rare is the contract in which teachers end up with less than they already had. The question is not even whether the strike improved the district’s offers; both sides are required by law to bargain in good faith, so it is even more uncommon to find negotiations in which neither side budges.

The question is whether the benefits gained from the strike exceeded the costs. In economic terms, what were the strike’s marginal gains? For example, the teachers ended up with a 16 percent pay raise, but they could have had that without surrendering six days of pay.

This kind of conclusion to the strike was certainly predictable. In fact, Politico reporters Shia Kapos and Adrienne Hurst did predict it, back on Oct. 3. “In the end, CTU and CPS could very well agree on a deal close to the one that’s already on the table,” they wrote.

So what did the strike achieve? Well, for the best part of a month, a wave of media attention has washed over Chicago schools and its teachers union. There have been rallies, marches and name-calling, all designed to draw the eye. Now that the strike is over, the attention will move elsewhere, but the union will try to ride that wave to increased membership numbers, political power and community support.

As long as that keeps working, there will be more strikes, regardless of the quality of the contract settlements.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)