Why Detroit’s $1.3B in COVID Relief May Not Be Enough to Both Fix Its Crumbling Schools and Rebound from a Year of Lost Learning

The long-struggling district scored more stimulus money per pupil than any other major system, but the needs in Detroit are deep and complex

When the federal government announced it would devote $190 billion in stimulus funds to help school systems recover from the pandemic, perhaps no district was in more dire need than Detroit.

Even before COVID, 9 in 10 middle schoolers in the shrinking city were below proficient in math and reading, many school buildings were structurally unsound and gaping budget deficits had landed the school system under the fiscal control of the state for the better part of the last two decades.

When relief funds began flowing, the challenges were great — a year of school closures and high absence rates had set students even further behind — but so were the means. The district scored nearly twice as much cash per pupil, over $23,000, as any other large system nationwide, thanks to a funding formula weighted for students living in poverty. Detroit has a median household income of $34,762, according to 2021 U.S. Census figures, and a childhood poverty rate roughly three times higher than the national average.

It was a test of the full power of federal relief dollars: Could $1.3 billion help get one of the nation’s most embattled school systems back on track?

Fast-forward two years and experts question whether the influx has delivered the needed boost to students. With more than half the money already out the door, less than 1% has gone toward bringing students back to classrooms, according to officials, despite two-thirds of the district’s 53,400 students last year missing school at a threshold researchers say puts them academically at risk. And the superintendent in March announced major staff layoffs to come in June.

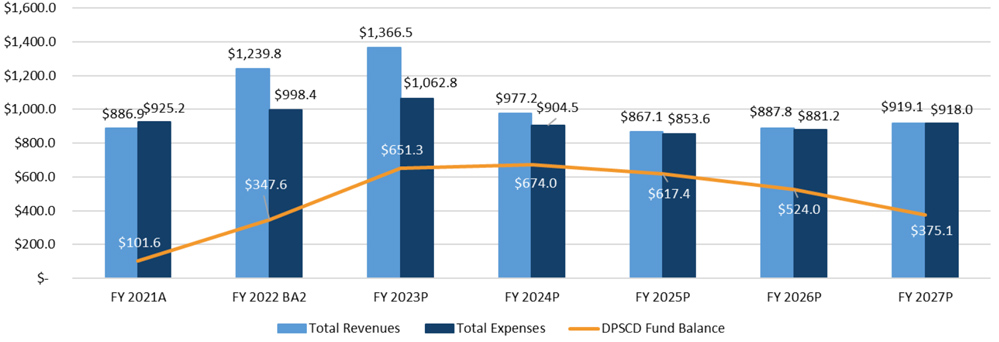

Meanwhile, the district is using $700 million of the relief cash on expenditures it normally pays for through its general fund, stockpiling money in its reserves for district-wide facilities upgrades over the next five or more years — a creative way to skirt the September 2024 deadline on the use-it-or-lose-it federal funds.

It would be “impossible” to complete the more than one thousand facility projects the district has planned in just a few years, Superintendent Nikolai Vitti told The 74 in an email. “Our students deserve to have roofs that do not leak or schools that do not close because outdated boilers break down.”

Taken together, the Detroit spending decisions paint a picture of both the promise and the pitfalls of schools’ handling of stimulus money. And they serve as a sobering reminder of what researchers have emphasized for over a year: relief cash alone likely will not be enough to offset the damage wrought by the pandemic.

Nearly a year behind

The scale of recovery efforts in Detroit and elsewhere falls short of the magnitude of learning losses, worries Harvard University education professor Thomas Kane, who researches COVID’s impact on education.

Comparing 2019 test scores to those in 2022, he calculates that students in Detroit fell nearly a year behind where they were previously. But he estimates the district’s key interventions — summer school for roughly 9,000 students and high-impact tutoring for about the same number — are only enough to spur about a fifth of the needed gains to get youth back on track.

“This is common in districts around the country,” the education economist said. “They can list the interventions that they’re fielding … but they’re not doing the math on the effect sizes that they should be expecting from those things.”

He suggests a quick sanity check: If students are a year back in their learning, catching them up will cost, at minimum, a district’s typical yearly operating budget. In Detroit, that would mean devoting roughly two-thirds of all relief dollars to academic recovery — a level the district is far from approaching.

District spokesperson Chrystal Wilson pointed out that the district is continuing to scale up small-group and one-on-one literacy and math help for struggling students. COVID money helped expand the effort initially, but now it’s built into the district budget so the support doesn’t disappear when relief funds dry up, the superintendent said.

As a result, a higher share of Detroit’s lowest-scoring students are on track to make a year’s worth of growth in reading and math this year than pre-pandemic, Wilson said.

Stacey Young is a Detroit mother of six, including three youngsters at Davison Elementary-Middle School. Last year, the school advertised tutoring and all three children attended, but the program enrolled more than a dozen students per teacher, she said, and her kids’ grades, which had suffered on the heels of virtual learning, did not improve. This year, her youngest son continues to struggle in math.

“On his report card, they said, ‘You need to seek some support,’” Young said. But the school had “nothing to offer” in terms of additional learning options, she said.

Superintendent Vitti recognizes the problem, but explained hiring staff for afterschool programming has posed a challenge.

“Our teachers are burnt out after the school day,” he said.

The students who remain the furthest behind in their learning also tend to be the ones who have had continued attendance challenges, he added, meaning the learning recovery efforts laid out by the district often miss the students who need them most.

“The issue here is not funding. The issues here are student access, quality human capital and the ability to scale human capital,” Vitti said.

Bernita Bradley, a parent advocate in Detroit with the National Parents Union, is frustrated that the district has also cut back on summer enrichment programs. After opening summer learning to all interested students in 2022, the school system will offer programming only to those in need of credit recovery this summer.

“There’s so much that’s needed for our children to catch up,” Bradley said. “This is the time for families to be getting more support … as opposed to canceling something.”

Fixing neglected facilities

It’s a delicate balance between shorter- and longer-term stimulus investments, because Detroiters — Young and Bradley included — acknowledge campuses across the city are sorely in need of repairs. The scale of efforts like tutoring or summer school are constrained in part because upgrades to buildings represent the single-biggest line item in Detroit’s COVID relief spending plan.

Capital improvements have long been on hold in the district because for most of the last two decades a state-appointed emergency manager controlled its purse, making budget cuts to close a longstanding deficit, explained Sarah Reckhow, associate professor at Michigan State University.

“An easy way to cut was simply to not spend money maintaining buildings,” she said.

It created a backlog of roughly a half-billion dollars in needed upgrades to fix issues like leaky roofs and moldy buildings, Vitti told NBC in 2019. Michigan is among the bottom five states nationwide for equitable school funding, according to a 2020 report from The Education Trust-Midwest, meaning the challenged district would have had to increase taxes on Detroiters to make facilities upgrades.

When the $1.3 billion COVID windfall hit, the district carved off $700 million to finally address conditions that many deemed shameful.

It’s a tactic common across high-poverty districts, which are more likely to have unmet infrastructure needs. School systems serving mostly low-income students have been far more likely than affluent districts to spend emergency relief dollars on facilities or transportation, a February Associated Press investigation found — meaning less cash leftover for academic support.

But from a fiscal perspective, it’s a prudent choice, said Elizabeth Moje, professor of education at the University of Michigan. Detroit’s schools need “massive renovations,” she said, and because the expenses don’t recur, the investment won’t contribute to future budgetary issues when federal funds dry up.

Still, doing so requires creative accounting as the construction projects will extend years beyond the deadline for spending relief money, said Phyllis Jordan, associate director of Georgetown University’s FutureEd think tank. Detroit is using COVID stimulus money to cover $700 million worth of expenses it typically pays for with its general fund, leaving the saved cash in its reserves with no spending deadline. The size of its general fund has swollen over 500% since stimulus funds began flowing and will be drawn down over the next five years, the district said.

“There’s a lot of that budget jiu-jitsu going on,” Jordan said.

Some 21 states, including Michigan, place no limit on the amount of money districts can keep in their reserves, allowing them to stockpile extra funds past the federal deadline so long as they first substitute COVID money for allowable expenses typically paid out of their general fund.

Meanwhile, a recently announced round of layoffs in Detroit was an even more bitter pill knowing so much cash is waiting unspent, educators said.

Daniella Borum is a college transition advisor at the Detroit School of Arts who was told in early April that her position, which she’s held since 2019, would be terminated. Now she wonders who will help the high schoolers on her campus through the stressors not only of preparing for higher education, but of navigating daily life.

“It doesn’t have to be Ms. Borum here as a college advisor, but the kids need [someone],” she said. “They need support services, period.”

Re-engaging students

A key component of COVID catch-up, in Detroit and nationwide, has been luring students back to classrooms. Student attendance took a major hit in the pandemic’s wake and chronic absenteeism, which researchers typically define as missing at least 10% of school days, reached unprecedented levels across the country’s largest districts — 69% last year in Detroit.

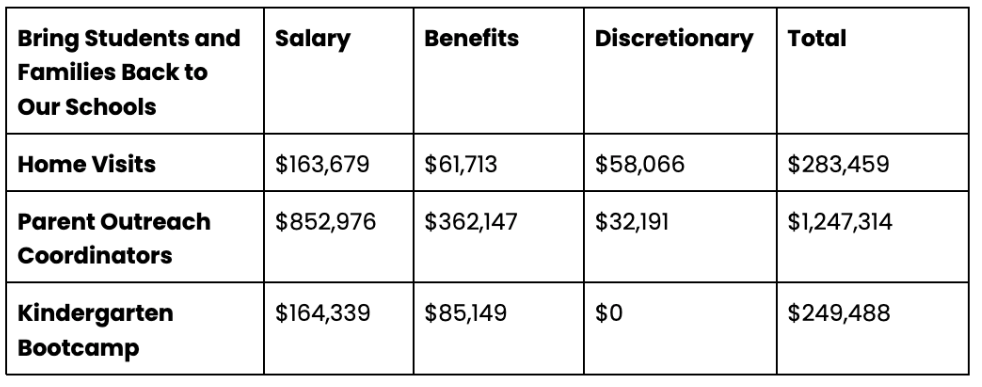

The district deployed staff to knock on the doors of families whose children were absent, seeing if there were ways they could help get those students to class.

“Families wanted their children coming back,” said Gwendolyn Jachim, a Detroit elementary school teacher who signed up to knock on doors in the summer of 2021. Still the conversations were difficult, and many parents remained unconvinced. She recalls virus-wary parents who, after the nearby Flint, Michigan, water crisis left children with lead poisoning, said they didn’t trust the government on public health matters.

For its youngest students, the district also ran summer boot camps to help children prepare for the transition into kindergarten. Detroit educator Kristy Kitchen co-led a cohort of a dozen youngsters in six weeks of programming, including weekly field trips. While the program’s past iterations had sometimes required teachers to purchase supplies themselves, educators last summer were flush with markers, science experiments and backpacks for students, she said.

“It was a very good opportunity for the kids,” Kitchen said. “They’ve had kindergarten boot camp prior to that year, but they didn’t have all those resources that we had.”

The two campaigns, door knocking and kindergarten boot camp, together amounted to roughly $1.8 million, according to figures provided by the district — less than 1% of its total stimulus allotment.

This year’s chronic absenteeism rates have dipped slightly to 60%, which the district attributes to its efforts. Still, 6 in 10 youth are missing class at a level that researchers say puts their education in peril.

Using stimulus funds, the district also invested in several fan-favorite activities aimed at boosting morale and engagement. The city paid thousands to vendors like Chuck E. Cheese, Top Golf, Video Game Mobile, Dave & Buster’s and Zap Zone Extreme, according to spending records obtained by The 74 through a Freedom of Information request. Some $47,000 went to field trips to Blake’s Orchard & Cider Mill, which Detroit Federation of Teachers President Lakia Wilson said is an annual tradition.

“These are city kids, so it’s good that they get to go out … picking their own apples, seeing pumpkins grow in a patch,” Wilson said. “You can’t live in Michigan and not go to the apple orchard.”

Contracts come under scrutiny

In a district with a past history of kickbacks and corruption, Detroit’s emergency relief spending has not been without its share of expenses some saw as questionable.

For its tutoring contract worth over $3 million, the district chose a vendor led by Superintendent Vitti’s wife, Rachel Vitti, ex-director of the literacy nonprofit Beyond Basics. Leaders disclosed the relationship when they discussed the contract in 2021 and said the provider was chosen because of its strong track record. Still, amid pushback, Rachel Vitti last summer resigned from her role leading the nonprofit.

And the district’s $68 million COVID testing contract received scrutiny for a price tag twice as high as the nearby University of Michigan’s, which used the same provider and served a comparable number of students.

The contracts “cannot be compared apples to apples,” Rebecca Throop, a spokesperson for testing provider LynxDX Inc., said in an email. Detroit schools requested a higher number of tests and the university hired staff independently to assist collecting samples, she said.

LynxDX Inc. is now a donor to the Detroit Public Schools Community District, listed as providing support at the $20,000 to $99,999 level.

“As a company, we recognize the importance of giving back to the communities we serve and where our employees live,” Throop said.

But zooming out beyond individual contracts, Reckhow, at Michigan State, sees the Detroit school district’s position as inherently difficult. The $1.3 billion is a lot of money, she acknowledges, but doesn’t think the time-limited boost can erase all the problems of the last decades.

“There’s the assumption that you get a one-time infusion of money and you recover,” she said. “But when you’re talking about a district where the needs are as high (as Detroit’s) and where the pre-existing issues of inequality were already enormously pronounced, the timeframe of these relief dollars is just not really up to the task.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter