Analysis: No Child Left Behind Was Signed 20 Years Ago This Month. Why It’s Making Education’s COVID Recovery So Much Harder

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

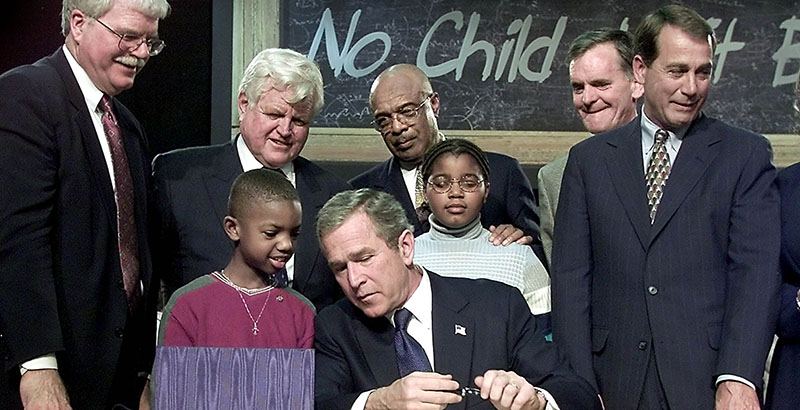

This month marks the 20th anniversary of the signing of No Child Left Behind, President George W. Bush’s landmark education legislation championed by bipartisan leaders ranging from Ted Kennedy to John Boehner. It was coherent, thoughtful and premised on a core theory as to why schools struggled: the soft bigotry of low expectations for students and insufficient attention to holding schools responsible for children’s learning.

While some good has come from NCLB’s core approach — notably a clearer focus on outputs over inputs, the disaggregation of student results by race and ethnicity, and a revolution in education data — it is hard to argue that the law has lived up to its promise. Roughly one-third of students graduated ready for college or a career back then, and the same is true today. Performance on international assessments haven’t moved in 20 years, while recent trends on the National Assessment of Educational Progress indicate that performance is going in the wrong direction.

Nor did NCLB put the nation on a path toward any semblance of educational equity, as achievement gaps haven’t shifted in two decades. Eight percent of Black 12th graders, for example, are now proficient in math — up from 6 percent back in 2005. At that rate of progress, it would take another 200 years for their performance to match that of white students, and that would assume white students’ performance stayed the same.

Now, as schools try to address the profound learning losses caused by the pandemic, the NCLB playbook seems wildly out of touch. Students returned to school this fall in need of real solutions to support their educational and social-emotional recovery following 18 months of profound disruption. But for many schools, the challenges of filling an unprecedented level of staffing vacancies, implementing COVID-19 precautions and managing parent politics have taken all priority. Accountability based on end-of-year grade-level assessments may well be the last thing on their mind.

Why did NCLB fail to deliver on its promise? Some will fault political opposition, economic conditions or bad implementation as key reasons, and there is some evidence to support each of these claims. However, we believe these explanations belie a larger truth that those who wish to improve our nation’s system of schooling can no longer ignore:

To modify the James Carville adage: It’s the model, stupid.

While NCLB shaped the foundation for the work of those looking to reform education, it left the basic century-old industrial paradigm of how schooling happens intact. Schools function, by and large, with all same-aged students learning the same material at the same time from a single teacher and textbook.

In the middle of the 19th century, this model was considered the most efficient way of supplying a factory-ready workforce that needed some assimilation and to be able to perform repetitive tasks, follow directions and apply basic numeracy and literacy skills. But from that point forward, nearly every effort at school improvement has been limited by its inherent constraints.

NCLB was only the latest of many well-intended school improvements that could not overcome the limits of the industrial paradigm of schooling. Raising academic standards can signal to teachers what they should expect, but they provide little guidance on what to do when students begin the school year multiple years behind. Good teacher training can make a big difference, but when skilled educators quit because of a fundamentally unsustainable role, it’s back to square one. Assessments can also be useful, but adjusting instruction to meet each student’s unique needs is near impossible. School choice can be a godsend for families whose children would otherwise be stuck in a low-performing school, but if the schools that are chosen are operating within the same industrial-era boundaries, differences may not be so stark.

Ironically, NCLB’s focus on trying to optimize a century-old delivery model took effect during the same time that other sectors saw the internet and its related technological advancements as an opportunity to modernize the ways in which they did business. From retail to energy to media to banking, the world of 2021 bears little resemblance to what existed at the dawn of the 21st century. Even churches now livestream on Sunday mornings.

Many of these shifts were funded by commercial forces looking to leverage modern technologies to capture new segments of the marketplace. When early-stage investment was deemed too risky for private capital, public investments in research and development stepped in to fund breakthroughs such as the internet, GPS and mRNA vaccines.

NCLB did little to stoke any form of R&D investment to modernize the K-12 delivery model. In 2001, the federal government authorized $264 million to the Department of Education to support R&D — dead last among all federal agencies. That expenditure was even lower in 2020 (and still dead last). And since the vast majority of education R&D dollars have gone toward research and not development, only about $50 million in 2020 was actually aimed at building things that schools could actually use. By comparison, the makers of Snapchat spent $1.1 billion in 2020 on R&D, exploring new ways for teens to send digital photos to one another.

Why has the industrial paradigm remained steadfast? Perhaps because there isn’t much effort aimed at creating any viable alternatives to it.

Beyond the lack of R&D, overcoming the limits of the paradigm was made even more difficult by the policies embedded within NCLB itself. Annual accountability for performance on grade-level-aligned exams meant everyone was on the hook for showing higher proficiency on the next year’s test. In response, many schools decided to hunker down and teach harder.

But when the pandemic hit, the implications of trying to improve schooling without really changing it were fully laid bare. While the general public was still able to do much of what it could do pre-pandemic — order groceries, watch movies, pay bills, stay connected to friends — schooling was reduced to teachers scrambling to bring their industrial-era classrooms online or somehow make them work in a hybrid context.

Make no mistake about it: It was optimization-only thinking at the heart of NCLB that left them in the lurch.

Parents are now onto all of this as well. Many had a front-row seat to Zoom school and didn’t like what they saw. A recent survey revealed they want to see more fundamental change in how school happens. On their wish list: relevant and real-world learning, improved technology to better support instruction and greater customization to meet varied learning needs.

While some schools and districts will take bona fide steps to respond to these aspirations, many know that systemically achieving them within the constraints of the industrial paradigm is futile.

It simply cannot be, in the 21st century, that the best way for students to learn about photosynthesis, parallelograms or the Vietnam War is through the pages of a tedious textbook in the company of 28 same-aged students. Yet, these core elements of an industrial paradigm from a time long past remain an ever-present design constraint that leaves millions of students bored, stressed and unable to access a high-quality education.

Nor does the factory-inspired model seem to work especially well for educators. Before the pandemic, teacher satisfaction had reached its lowest level in two decades. Now, more than a quarter of educators want to quit. The pandemic made them more comfortable using technology, but the burden of reimagining what a classroom can look like cannot fall on their shoulders.

If our ways of education are not working for students, for teachers or for the nation, how long will we continue down this path without laying the foundation for new ways of schooling? Can we not conceive of more effective ways to educate students that are not viewed through the industrial-era prism?

The architects of NCLB were right: Expectations matter. However, policies that center exclusively on optimization around the existing model of schooling reflect just the opposite — that the century-old way of doing school is simply the best we can hope for in the 21st century.

It’s not.

As policymakers look forward to more recovery investment and to future reauthorizations of the federal education law itself, they would be wise to heed the most important lesson from the last 20 years:

Our nation cannot force an educational system that leaves no child behind. It must invent one.

Jenee Henry Wood is head of learning at Transcend, a national nonprofit organization that supports communities to create and spread extraordinary, equitable learning environments. Joel Rose is CEO of New Classrooms Innovation Partners, a national nonprofit organization focused on the development and adoption of innovative approaches to learning that personalize education for each student.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)