Analysis: New Study of DCPS Examines Why High-Performing Teachers Leave — and What Can Be Done to Retain Them

Teacher Appreciation Week means lots of candy bars, apple magnets, and pep rallies in teachers’ honor. But are these gifts what mean the most to today’s teachers? In a new Bellwether analysis, we studied DC Public Schools’ teacher exit survey data to figure out why teachers were leaving the district, where they were going, and what DCPS could have done to keep them. By disaggregating the responses by teachers’ latest performance ratings, we were able to zero in on potential strategies for retaining the best educators in the district.

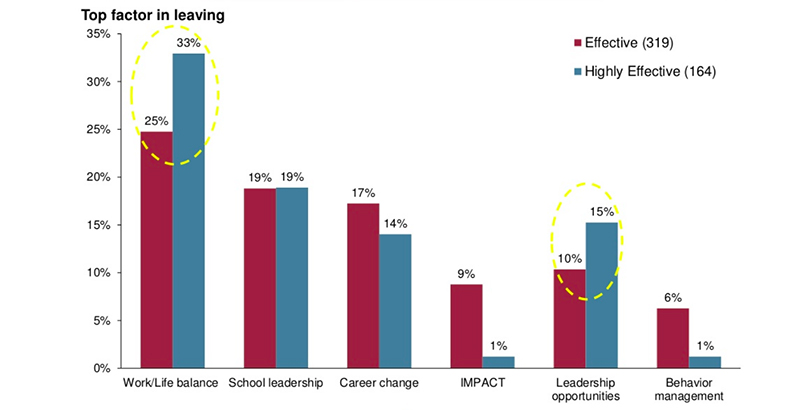

The top job-related reason highly effective teachers cited for leaving was work-life balance. This makes sense: Good teaching is hard, and it’s even harder in a district where 3 out of 4 students are economically disadvantaged. The second most common factor was school leadership. Also understandable, because a principal’s impact on teachers’ day-to-day satisfaction is enormous. However, the third factor intrigued us. Fifteen percent of highly effective teachers left the district to pursue a leadership opportunity somewhere else. These are educators who want to grow in their profession and take on more responsibility as they gain proficiency.

For the average public school district, this wouldn’t have surprised us. Many districts lack a streamlined, transparent career ladder that rewards performance and lets early career teachers take on responsibility. But DC Public Schools is not one of them.

In 2012, DCPS launched the Leadership Initiative for Teachers (LIFT), a five-stage career ladder on which teachers advance based on their annual performance rating. With each new stage, teachers have access to a host of opportunities for growth, possibilities to coach and mentor others, or engage in policy and curriculum design. Since 2013, the Teacher Leadership Innovation program has let high-performing teachers reduce their teaching load and spend part of their day coaching their colleagues. After five years of pedagogical experience, teachers can apply for the Mary Jane Patterson Fellowship for Aspiring Principals, DCPS’s 30-month-long principal preparation program.

Now, we have no way of knowing how many more teachers might have left DCPS had it not been for LIFT. But according to teachers, the district still has more to do to retain its aspiring leaders.

This is especially true for teachers of color, who cited leadership opportunities as the No. 1 factor that would have kept them in the district, while white teachers put “more leadership opportunities” only in fifth place, after retention efforts related to school leadership and work-life balance. This data point alone is reason enough for DCPS to examine their leadership pipeline and consider reaching out to teachers of color or addressing issues of bias in hiring decisions.

Where did high-performing teachers eager for leadership opportunities go after DCPS? While most continued working in a public school district, we found that those leaving for a leadership opportunity were more likely to switch to the charter sector. In fact, the share of high-performing teachers switching to a charter school tripled when just considering the subgroup that left for a leadership role.

Research shows that, compared with traditional districts, charter principals typically have fewer years of teaching experience before becoming a school leader. In some charter school networks with high teacher turnover, it’s not uncommon for teachers to be promoted to the principal role in their early 30s. So are teachers switching to charters to get promoted faster? Are aspiring leaders perhaps deterred by the red tape that comes with public school leadership? Or is there some other reason?

We would need more refined exit surveys to understand how teachers make these decisions.

Still, we were able to identify some potential strategies for keeping the best educators in the district:

● Give experienced teachers more options for extended leave and part-time employment.

● Make sure school leaders show encouragement and recognition, and provide behavioral and instructional support.

● Pay attention to what high-performing teachers want and where they go when they leave, to learn about specific changes or incentives that would retain them.

● Don’t focus on retaining potential career changers, as most say there was nothing the district could have done to retain them.

● Market opportunities for leadership toward teachers of color and address potential bias when hiring for leadership positions.

Even though 92 percent of high-performing teachers stay in the district, as any student will tell you, every great teacher matters. And retaining them, especially teachers of color, should be top of mind in any school district.

Kaitlin Pennington is a senior analyst with Bellwether Education Partners in the policy and thought leadership practice area. Alexander Brand is an intern in Bellwether’s policy and thought leadership practice area and a candidate for a master’s degree in STEM education from the University of Augsburg in Germany.

Disclosure: Andrew J. Rotherham, a co-founder and partner at Bellwether Education Partners, is a senior editor at The 74 and serves on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)