Analysis — The Summer Puzzle: At Many Districts, Summer School Plans to Date Are Lacking

This analysis originally appeared at The Lens, the Center on Reinventing Public Education’s blog at the University of Washington Bothell.

Last April, school districts were one month into unanticipated, universal closures and still figuring out the basics of their spring remote learning plans. Many school districts were overwhelmed by shifting basic operations like access to critical services and laptop distribution. It is not surprising that summer planning in 2020 felt a bit like putting together a puzzle with pieces from different boxes.

This year, however, we are in a vastly different situation. Districts have a year of experience with remote and hybrid learning. Vaccination efforts are well underway. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona has set in motion a variety of support programs and guidance for state and local leaders, and Congress has passed a tremendous stimulus bill that provides districts with nearly $122 billion for addressing pandemic impacts.

Given all of these unmatched supports and only months until summer arrives, it is noteworthy that school districts have put out so little information about 2021 summer learning and enrichment plans. Moreover, many of the plans released are missing high-leverage strategies being discussed by experts across the country, like tutoring, assessment data, and clear communication plans.

Districts release limited summer programing plans this spring

CRPE’s review of 100 urban and large school districts for summer plans finds that, similar to last year, most summer school plans are vague. A significant majority lack explicit learning supports and feature incomplete or confusing messaging.

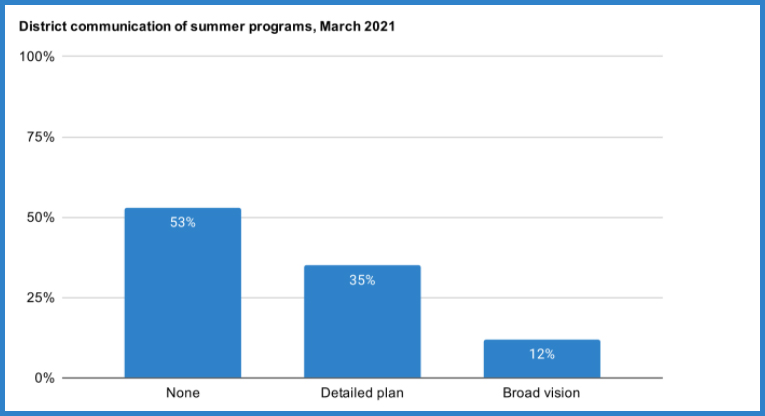

A little more than half of the districts—53 of the 100—do not share information on summer plans at all.

The others report a variety of summer learning and enrichment options. About a third—35 of the 100—have released detailed plans, including offerings broken down by grade band, learning mode options, program dates, and availability of programs targeting specific groups such as multilingual students. Some have already opened registration or presented their plans to their school boards.

The final 12 districts commit to a broad vision of summer school but lack specificity and transparency in what summer learning and enrichment options will look like.

For districts with detailed plans, specifics vary

In early March, Saint Louis Public Schools presented a summer learning plan that incorporated information about their planning committee and a tiered approach to address learning recovery, as well as postsecondary support and project-based learning options. Most importantly, their communication plan, their outline for proposed timing, and progress to date are explicit and accessible. Boston Public Schools has released a detailed plan for projected number of seats and costs by program focus, like credit recovery or summer enrichment. The School District of Philadelphia is hosting information sessions for families to learn about summer program options and is clear with parents about the risk of summer slide and the value of academic programming during those months. A Philadelphia parent would easily be able to find information about summer learning opportunities that are most appropriate for their children.

Thirty-three districts say how long their summer program will be, with a range from two to eight weeks. Twelve districts are offering a month or less of summer learning and enrichment, while 21 districts are offering five or more weeks. Dayton Public Schools is offering free two-week summer camps for students in grades 1 through 12 who need extra instruction. Orange County Public Schools is offering a longer, eight-week summer program for students in elementary to high school.

Summer learning plans may not meet students’ personalized learning needs

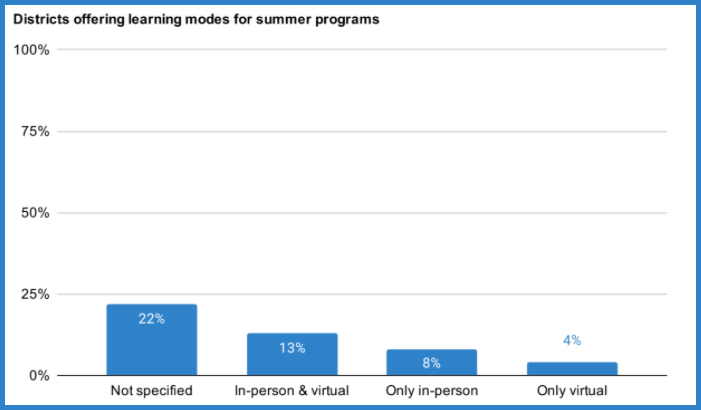

Of the 100 districts we reviewed, 47 released information on their summer learning plans—and nearly half of those (22) provided no information about learning mode. Among the others, a majority (13) will offer the choice of in person or virtual; eight will offer only in-person learning, and four will offer only virtual learning.

Some of the virtual summer programs will include both synchronous and asynchronous instruction. San Antonio Independent School District, for instance, will offer the Digital Learning Playground for PK-8 students, which blends the two. Such an approach accommodates the significant swath of families who prefer a remote learning environment, but it is unclear whether such virtual-only approaches will provide enough individualized learning or opportunities to rebuild relationships.

While many districts describe how students can enroll in summer learning, only one of the 100 districts said diagnostic assessments will be used to determine which students need summer learning.

That district, Shelby County Schools, in Tennessee, plans to prioritize students using two assessments, but will not mandate anyone’s participation. In addition, Shelby County Schools will increase the amount of learning time over typical summer weeks by decreasing summer school weeks and moving up the start of the 2021–22 school year.

After a year of unprecedented disruption, it’s discouraging that more districts are not, like Shelby, using assessment and academic data to determine which students are most in need of summer learning support.

Districts focus heavily on summer enrichment programming, for better or for worse

This year’s summer programming has the potential to simultaneously provide individual student instruction while helping schools prepare for good assessment, tutoring, and personalized support in the fall.

School districts are most frequently offering opportunities for enrichment, academic content, credit recovery, and learning acceleration for summer 2021:

- Twenty-three districts will offer enrichment programs. For example, Gwinnett County Public Schools plans summer enrichment and acceleration for students in grades K-8.

- Twenty-one districts will offer reading/math programs. For example, Atlanta Public Schools Academic Recovery Academy (ARA) is a full-day summer program for all grade levels that combines literacy and math learning.

- Eighteen districts will offer credit recovery programs, like Milwaukee Public Schools. Nine districts will offer learning programs. For example, Kansas City Public Schools plans summer accelerated learning in preparation for the 2021–22 school year.

Among the significant number (23) of school districts who identified enrichment as a top priority, community partners were often incorporated into plans for additional services and support. Leveraging community partners in this way builds on communities’ strengths and allows districts to prioritize the delivery of other—likely academic—services. Columbus City School Board of Education outlined multiple partnerships with local organizations, such as the historical society and conservatory. In March, San Francisco Unified School District established a coalition of community organizations, nonprofits, and business leaders for Summer Together, a free program for students and families.

What is most worrisome is what’s missing in 2021 summer school planning

So far we’ve reported on what we noticed, but what is most troubling are the things we didn’t see in the 47 plans reviewed:

1. High dosage tutoring. Despite the growing evidence base and broad support for high dosage tutoring, this strategy was almost completely absent in the summer programs we reviewed. Only one district outlined a detailed plan for tutoring: in Idaho’s West Ada School District, the tutoring will be available by appointment only.

2. Standardized assessment data. With many districts forgoing their typical testing schedules this year, either interim or summative, it is not surprising that prioritizing students using assessment data are not included in more of the summer learning plans. That said, without end-of-year data, it will be difficult for school districts to identify priority students for inclusion in summer programs or determine the extent to which students receiving special education services are in need of compensatory education. Lack of student academic data will leave educators and leaders flying blind as they prepare for summer and fall and leaves the door open for reductive strategies to address unfinished learning (e.g., interventions targeting content from earlier grades).

3. Public transparency about funding. Twenty percent of the American Rescue Plan funding for education agencies must be used to address learning loss. This category is very expansive and includes summer programming and extended learning time as options for expenditures. Because districts have not yet shared details on how they will spend the first tranche of these funds, it’s unclear how much districts will rely on these funds for 2021 summer school and the extent to which they will be transparent about their funding strategies.

This is an initial analysis describing the landscape of what summer learning and enrichment opportunities we may see this year. As district plans develop and evolve we are hopeful that the puzzle pieces will come together with more clarity and grounding in the things we know will help students prepare for another unprecedented fall.

Dr. Christine M. T. Pitts is Research and Evaluation Manager at Portland Public Schools. As a facilitative leader, she also collaborates and coordinates across policymakers and state leaders to investigate and advocate for policies that prioritize equity in education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)