Analysis: Minnesota Cheers a Booming Graduation Rate — Even as Fewer of Those Grads Can Read or Do Math at a High School Level

Some years ago, I was visiting with an inmate in a state prison, a young black man. We’d finished combing through his case, which was a study in sundry miscarriages of justice, and were making small talk.

“You know what gets me about this place?” he said, gesturing at the other convicts in the concrete block visiting room. “All these guys graduated from high school.”

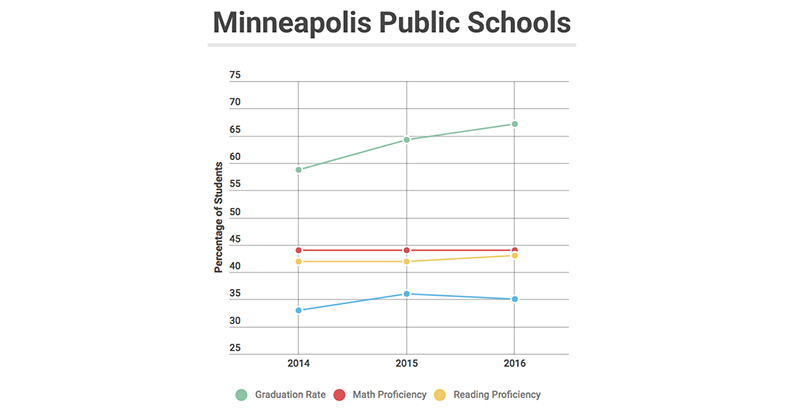

Covering courts, I didn’t get his point back then. But I thought about him the other day upon reading an analysis published by MinnPost, a nonprofit Minnesota news site where I used to work, showing that graduation rates in the state are rising even though other measures of academic achievement are not. The problem is particularly acute in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

For young people from families that aren’t affluent, a high school diploma marks the end of the education we, as a society, have long agreed should prepare them for citizenship and a job, if not college. Diplomas notwithstanding, many of the inmates in the room couldn’t fill out an application for a job at McDonald’s or calculate the price of a dozen Happy Meals.

The MinnPost story sketched a laudable rise in recent years in graduation rates but sounded a cautionary note. “Establishing high graduation expectations seems essential to ensuring the state has a more equitable public education system,” wrote Erin Hinrichs. “However, gains on this front are often celebrated — in the media and by state education officials — out of context. While graduation rates are on the rise, proficiency rates in math and reading have remained relatively stagnant. And for some student groups, proficiency rates have actually decreased at the same time that their graduation rates have increased.”

In short, the number of students who graduate without being able to read or do math at a high school level is going up. And although it’s hard to argue that life with a diploma isn’t preferable, I worry that celebrating huge gains in the graduation rate masks the fact that nationwide, millions of students of color and Native American students still are being left behind.

This isn’t a Minnesota problem per se; it happens to be the place where I, as an education reporter and parent of two, have watched a succession of strategic plans and accountability systems attempt to alternately illuminate and cloud how well schools are serving their neediest students.

Consider Minneapolis Public Schools’ Roosevelt High School, which sits solidly in the middle of its district in terms of socioeconomics. Between 2014 and 2016, its graduation rate rose from 58 percent to 75 percent. During the same time, reading proficiency — the number of 10th-graders who pass the 10th-grade reading exam — fell from 18 percent to 14 percent. Proficiency in math, assessed in 11th grade, fell from 18 percent to 12 percent.

Significantly, this chasm between literacy and numeracy and graduation rate opened wide after passage of a state law that put increased emphasis on high school graduation.

Between 2013 and 2016, the number of Latino students graduating from Roosevelt nearly doubled, from 43 percent to 80 percent. The percentage passing state tests, meanwhile, has been nearly flat at 8 percent. The percentage hitting targets for academic growth started at 41 percent, fell to 14 percent in 2016, and rebounded to 25 percent last year.

Critics of standardized tests rightly complain that they provide but one snapshot of students and schools, but given what I have just told you about three very different high schools, would we be able to pinpoint inequities based on graduation rates alone?

It’s not an issue particular to Roosevelt. Across the city, at the most impoverished high school, North Community, a rising graduation rate is being celebrated despite the fact that the number — not the rate, but the number — of students passing the exams has ranged from two to seven. The composite score of the 70 North students who took the 2016 ACT was 15.7; Minnesota’s lower-tier state colleges generally look for a 22 on admissions applications.

The graduation rate in the district’s wealthiest, majority-white school — Southwest High, which my older son graduated from — rose from 80 percent in 2012 to 90 percent in 2016. Alas, it’s impossible to say whether proficiency and growth among these high achievers fell like it did in other, poorer schools, because almost none of its students — egged on by many of their teachers — took the annual state assessment.

Which underscores a crucial point: Critics of standardized tests rightly complain that they provide but one snapshot of students and schools, but given what I have just told you about three very different high schools, would we be able to pinpoint inequities based on graduation rates alone?

One of the earliest lessons an education reporter learns is that graduation rates are notoriously fungible. Rarely does this data point reflect what it sounds like it should: the number of students who started in a high school in ninth grade and received a diploma by the end of 12th. Rates rise and fall according to a dizzying array of factors.

Are students who were expelled or pushed out counted? Those who were referred to an alternative learning center? What about students learning English or persisting with a disability, who in some places are given extra years of schooling? Or one I’ve never gotten a graspable answer to: What’s the difference between a dropout and a student who is simply no longer attending any school?

It’s also a statistic that’s not hard to manipulate. Between 2011 and 2016, the Los Angeles Unified School District saw a phenomenal 20-point rise in its graduation rate. The Los Angeles Times attributed 13 percent of LAUSD’s graduation boom to online credit recovery classes whose integrity has been challenged.

“As a Times editorial revealed in 2016, the online courses, created by an outside vendor, are of dubious value,” the paper reported. “They have a well-designed curriculum, but they’re set up so that students can skip entire units by taking 10-question, multiple-choice quizzes beforehand.”

At the same time, notes the Brookings Institution, the district’s passing grade was lowered to a D — never mind that a D in a core course would leave a graduate ineligible to enter any college in the University of California or California State systems. Minneapolis students, too, pass with a D.

Down the Pacific Coast, in San Diego, a months-long tussle over public records between the nonprofit news organization Voice of San Diego and San Diego Unified Schools led to the revelation that the district’s eye-popping 91 percent graduation rate was partly achieved with a D standard and online credit recovery.

Another factor revealed by the public-affairs news site: San Diego students who were not on track to graduate were often counseled out of district schools.

Students “said they were informally advised by staff members to transfer to charter schools due to low grades and problematic behavior,” one story reported. “At least 30 percent of the students from the class of 2016 left a San Diego Unified high school for a charter school after the start of their freshman year, according to numbers the district has provided.”

I’ve had a photo pinned up over my desk for years, sent to me by the inmate I was visiting 14-plus years ago. He sent it to me during an optimistic window when he thought he would be able to go to barber school or learn another trade and support the baby boy he’s pictured taking a nap with.

I checked in on him this morning. Public records reveal he’s been on probation for three years. He’s 42. That baby boy is the age of one of my own, presumably college-bound, sons.

I know what the statistics predict, but I’d like to think that somehow he’s on track to graduate and that his diploma truly will equip him to interrupt the cycle he was born into. We all need that to become true.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)