Analysis: Halfway Through the Last Quarter of the School Year, Remote Classes Are in Session but Attendance Plans Are Still Absent

A version of this essay appeared on the Center on Reinventing Public Education blog.

Six weeks into COVID-19 school closures, and at roughly the midpoint of the final academic quarter of this school year, it is a good time to step back to assess what schools and districts have accomplished — and the gaps in learning opportunities that remain — as students, teachers and families prepare to close out 2019-20.

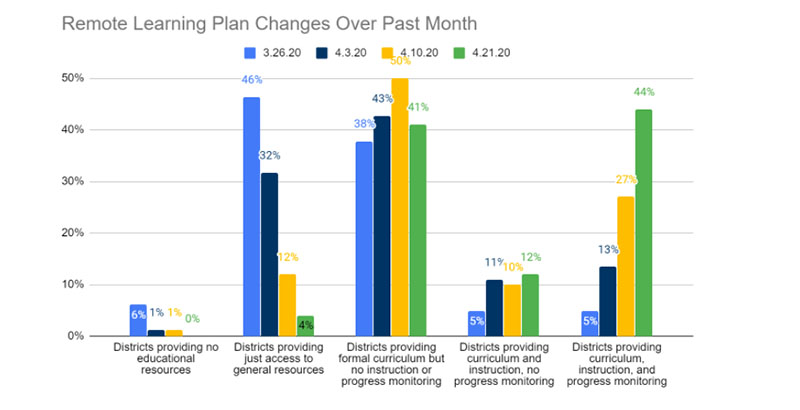

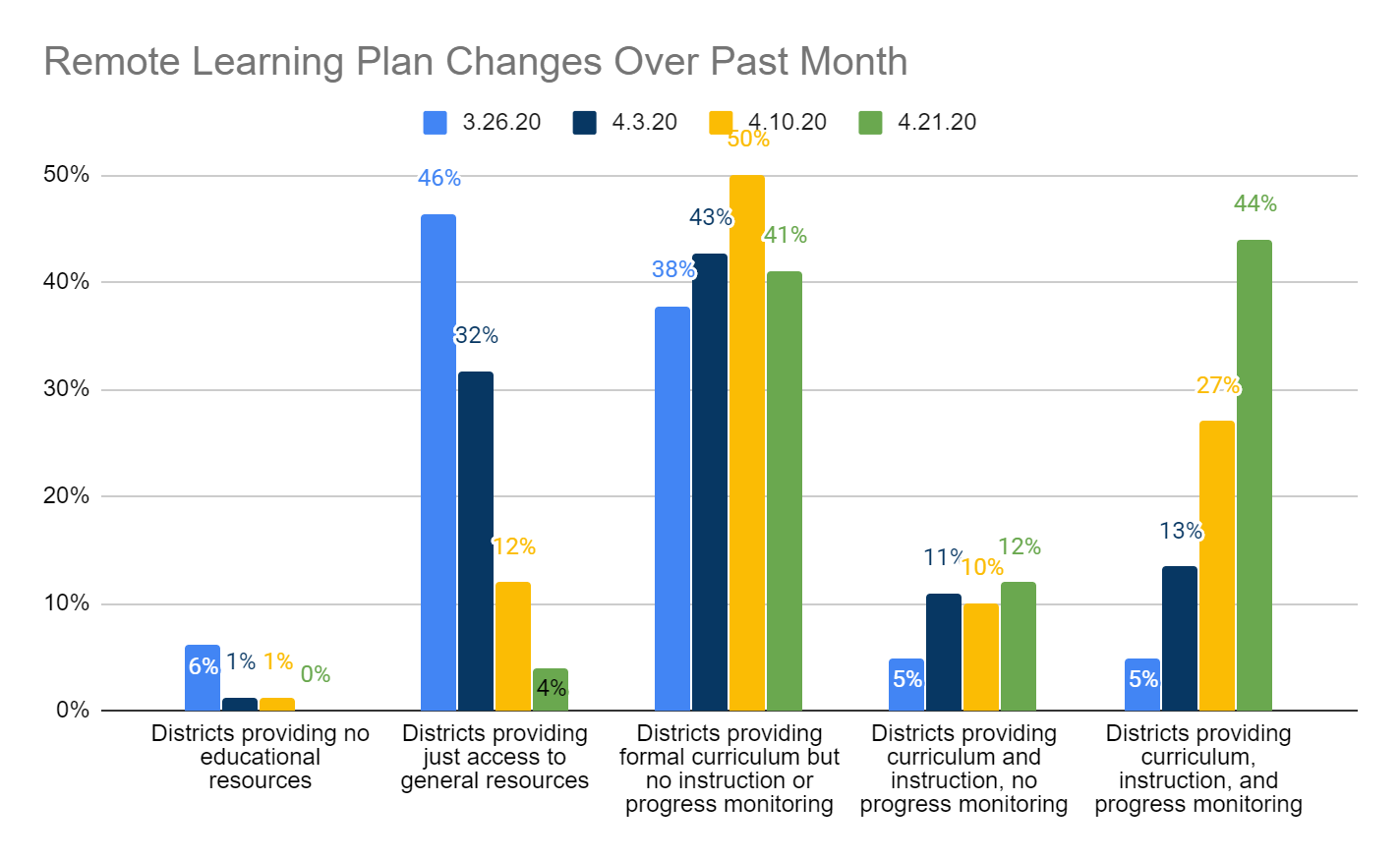

Districts have come a long way in this time. Over the past month, the percentage of 82 districts reviewed that provide a comprehensive remote learning plan (one that includes access to formal curriculum, instruction and feedback on student work) has increased from 5 percent to 44 percent.

Assuming that districts’ attention will soon turn to commencement celebrations, summer learning and fall contingency planning, it is not clear how much more progress will be made on remote learning this school year.

The districts that embarked quickly on ambitious remote learning plans may be in the best position to succeed in 2020-21. They will be able to build on the lessons learned from this spring about how to support students and teachers in remote instruction. They will be able to strengthen their systems, expectations and communications in preparation for future remote learning — which could include continued closures or partial reopenings next school year.

Also notable is that 100 percent of districts reviewed are providing access to educational resources, and almost all — 96 percent — are providing formal curriculum.

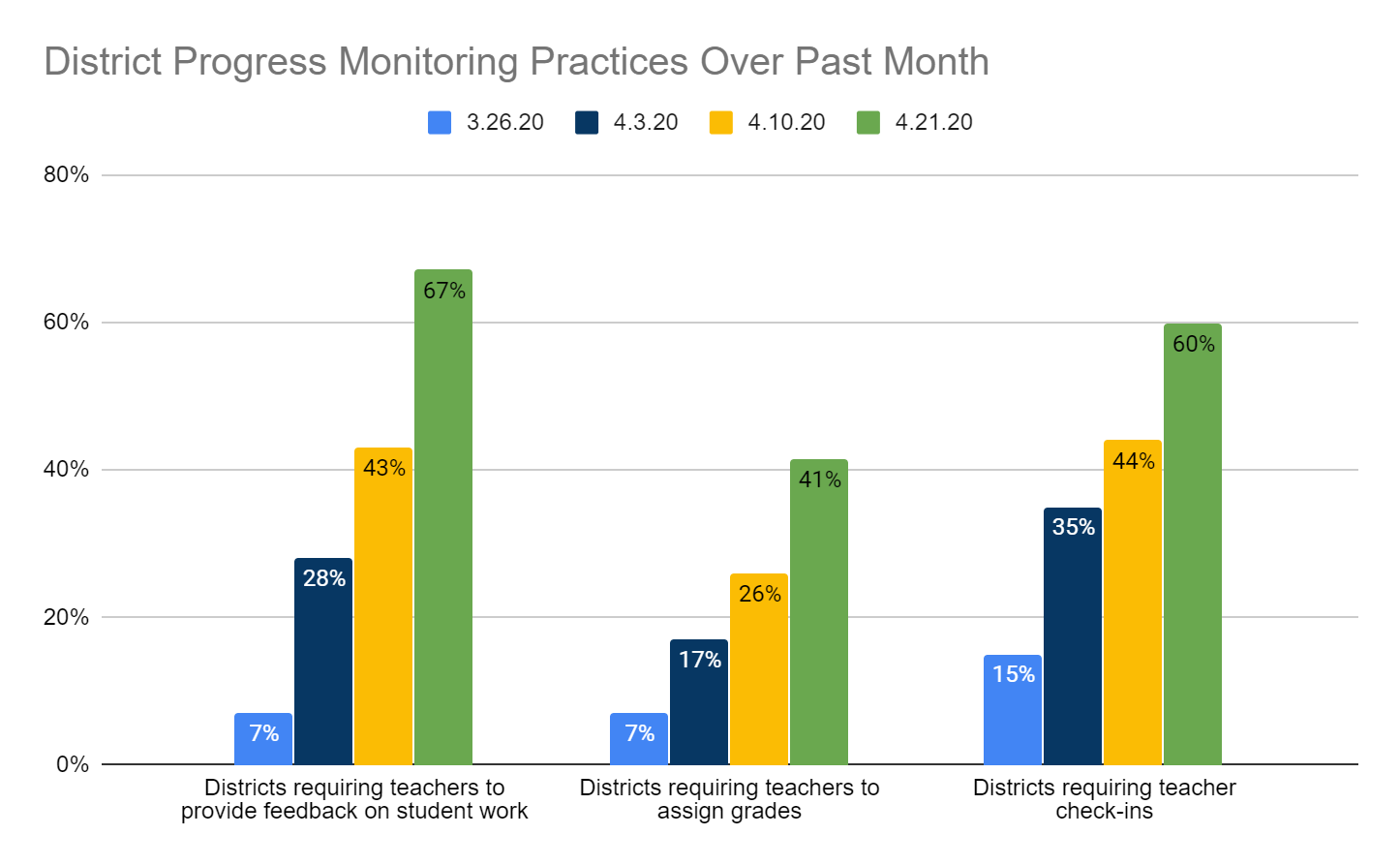

Districts reviewed make steady progress on all of our independently tracked measures of student progress monitoring. About two-thirds require teacher check-ins and feedback on student work. Slightly fewer than half assign grades.

Districts are settling into remote learning plan delivery while clarifying expectations

The movement we did see this week may be the result of states’ confirmation that schools would not reopen this year. A few districts — Detroit and Sacramento are two examples — rolled out new, comprehensive plans this week. The Motor City released its plan after securing tens of thousands of devices and internet connections for its students. Colorado’s Boulder Valley, which rolled out its comprehensive plan over a month ago, just released plans to assess students now to determine which would benefit from small-group summer school. The district plans to reassess students in the summer to determine fall assessment and intervention plans.

We have also seen a few districts now providing more specific guidance after delegating decision-making to schools. Minneapolis Public Schools, which originally implemented remote learning by having teachers design and distribute curriculum, strengthened its articulation of a centralized plan for expectations, grading and instructional time.

The majority of districts that led the pack in remote learning planning, such as New York City, Miami-Dade County, Duval County (Florida) and Fort Worth, seem to have settled into executing and not changing their plans, likely expecting to stay the course through the end of the school year.

But they still have problems to solve. And some districts might not be collecting the data they need to identify and solve gaps that persist in their remote learning plans.

Districts are still largely absent in tracking student attendance

There was little movement in attendance tracking systems, an indicator we just started to follow in our last report. Just 16 of 82 districts reviewed (20 percent) report using a system to track attendance, up from just 14 districts (17 percent) since last week.

Districts that track attendance are using the data to identify, locate and solve problems with access for missing students. All three large school districts we reviewed from southeast Florida — Broward, Miami-Dade and Palm Beach counties — are monitoring attendance. Broward County is treating its district as one virtual school and tracks attendance through online logins and student work submission. Its daily average attendance is at 90 percent. Staff are reaching out to families to solve technology access issues for those who lack laptops and internet connections. According to a video message from Superintendent Robert Runcie, the district’s social workers have received 4,400 referrals for their services and provided more than 9,700 interventions to students and their families since returning from spring break March 30.

Miami-Dade reports that 99 percent of its students have logged onto their online platform and that average daily attendance is around 92 percent. Superintendent Alberto Carvalho has previously called out the “digital desert” that many Miami-Dade students face. He is now directing staff to use these data to call and conduct home visits for missing students and provide laptops and training to parents.

States can require districts to collect attendance data that help ensure that all students have access to remote learning. However, some, such as Ohio, have directed districts to mark all students present. Other states, such as Georgia, have waived state attendance policies during the crisis, or signaled to districts that they will not be penalized in average daily attendance calculations for funding purposes, as Missouri has done.

Colorado has encouraged districts to track attendance but has not required it. Some Colorado districts in our database (Denver and Boulder) are tracking attendance, while others, such as some Denver-area schools, are not.

Wyoming has set a statewide expectation that districts monitor attendance during remote learning and has secured commitments from all 48 districts that they will do so. The state appears to be one of the standard-bearers when it comes to setting clear expectations for remote learning and following up to make sure districts meet them.

While states may play a role in attendance reporting, simply tracking attendance data provides invaluable information for districts’ efforts to ensure that all students can access remote learning. We hope to see more districts piloting attendance tracking and response strategies in the remaining school year.

Robin Lake is director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell. You can find her on Twitter @RbnLake. Bree Dusseault is practitioner-in-residence at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, supporting its analysis of district and charter responses to COVID-19. She previously served as executive director of Green Dot Public Schools Washington, executive director of pK-12 schools for Seattle Public Schools, a researcher at CRPE, and as a principal and teacher.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)