Analysis: Focus on Grade-Level Standards or Meet Students Where They Are? How an Unintentional Experiment Guided a Strategy for Addressing Learning Loss

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

What’s the best way to support learning recovery in middle-grade math?

Should schools stay focused on teaching all students the standards that correspond to their enrolled grade levels while trying to address critical learning gaps as best as they can? Or should schools systematically address individual students’ unfinished learning from prior years so they can ultimately catch back up — even if that means spending meaningful time teaching below-grade skills?

It is a question that teachers and administrators are wrestling with as they prepare to return to school in the fall. Many will acknowledge that addressing unfinished learning in middle-grade math was a challenge long before the pandemic. It’s now just far more acute.

The nonprofit organization I lead, New Classrooms Innovation Partners, spent the last decade digging deeply into this question. We’ve consulted with top educational researchers and experts, dissected standards into their component parts, mapped out and refined how different math concepts relate to one another, and reviewed tens of thousands of high-quality lessons that we integrated into the innovative learning model we operate across the country — Teach to One.

Teach to One uses precise information about each learner to generate a personalized curriculum that includes a strategic mix of pre-grade, on-grade and post-grade concepts designed to best support his or her acceleration. To learn these concepts, students spend part of their time working with teachers, part of their time working collaboratively with peers and part of their time working independently. Daily assessment data then feeds a state-of-the-art scheduling engine, which works behind the scenes to organize the classroom so that each day, each student can experience the right lesson at the right time and in the right way.

We’ve been able to significantly enhance the program over time based on feedback from teachers and analyses of the millions of academic data points generated by the program itself. But it was actually an accidental experiment that may have shed the most light on a big key to acceleration.

In 2018, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded a study that examined the impact of Teach to One in 14 middle schools that used the program for three consecutive years. The study was focused on the learning growth that students demonstrated on NWEA’s Measures of Academic Progress, or MAP, from sixth to eighth grade.

We were a bit nervous about the study, but not because we didn’t believe in the program. What concerned us was the fact that in many schools, our desire to address students’ unfinished learning from prior years was ultimately overruled by a district or school administrator who insisted we adjust the program’s algorithms so that students would spend more time with grade-level material instead. The reason: State exams, which served as the basis for school accountability, were almost exclusively focused on grade-level standards. Student instruction needed to align with what was to be tested.

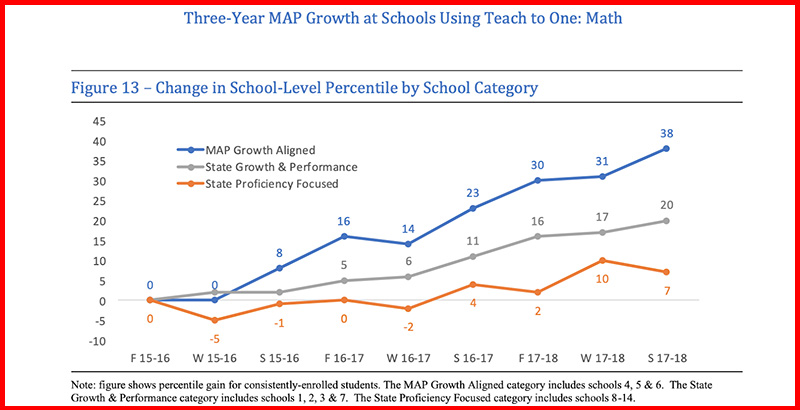

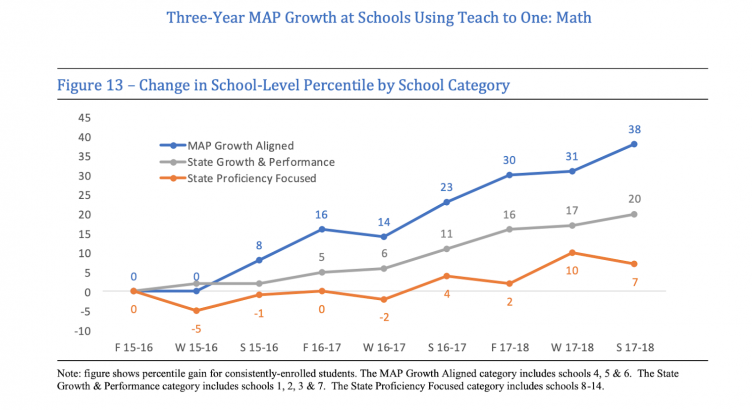

The study ultimately showed the scores for all participating schools grew, on average, 20 percentile points — a result that far exceeded our expectations. But the most interesting finding wasn’t the overall gains, but the performance difference between schools that prioritized grade-level exposure and those that permitted more student-centered instruction. The study found that performance in schools with accountability systems that focused on state grade-level proficiency (and thus prioritized grade-level exposure) grew 7 percentile points, while those that operated under accountability systems that rewarded student growth (and thus prioritized individual student needs) grew 38 percentile points.

While we had never intended to compare results across schools in this way, the stark difference in growth between the two groups could not be ignored.

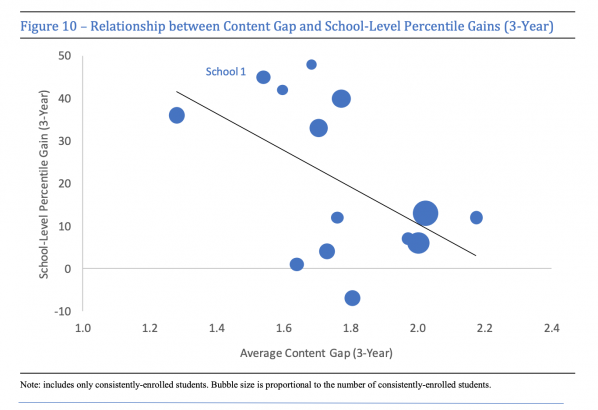

In addition, the study leveraged some of our internal data to explore a concept called the content gap, defined as the difference between the grade level a student tests at and the average grade level of the content he or she was exposed to.

In comparing students’ content gaps to MAP gains, the study found evidence that schools with a smaller content gap — those where math lessons better matched students’ actual performance levels (as opposed to their grade-levels) tended to see greater gains.

The study had its limitations. As with any school-based program, there are a number of factors — including curriculum implementation, teacher quality, staffing and external issues — that can influence outcomes. The study was not structured to establish causality. And it applies only to middle schools. (One recent report suggests that elementary school students benefit from more grade-level exposure. That may be because it’s harder in the elementary years for students to be multiple grades behind.)

But the research should also be viewed in contrast to the stronger evidence base for the negative effects of promoting students into higher grades without the requisite foundation. A policy push in the early 2000s placed many eighth-graders in algebra instead of a pre-algebra course. One California study found increasing eighth-grade algebra enrollment had a negative effect on students’ achievement. A national study using NAEP data drew similar conclusions.

Expectations matter, and there is ample evidence that in many schools, and across many subjects, schools simply do not expect enough. The movement toward the widespread adoption of grade-level-aligned instructional materials, assessments and accountability mechanisms was put into place to guard against the pernicious effects of these biases.

But expectations are not all that matter. Students need viable paths to achieve college and career readiness when they stray from the standard grade-level path. This is why those of us who argue for more personalized pathways believe we must challenge the conventional wisdom around grade-level exposure. The bar for college and career readiness cannot shift one inch — but in math, students need more ways to bridge where they are starting from to where they need to be, as Dan Weisberg of TNTP and I discussed in 2019.

Math is cumulative, and the path to proficiency often requires addressing unfinished learning from prior years. For the middle grades, administrators and policymakers would be wise to question the grade-level-only gospel as they begin to plan students’ educational recovery.

Joel Rose is co-founder and CEO of the nonprofit New Classrooms Innovation Partners.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)