Analysis: Arizona Leads in Academic Growth — and Both Charter and District Schools Contribute to Student Success

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Correction appended May 10

In 2001, the Manhattan Institute ranked states by their combination of public charter, private and home-school choice. Arizona ranked first. In 2015, the Brookings Institution measured the percentage of students who had access to one or more charter schools in their zip code. Arizona ranked first in the nation, with 84 percent of students with a charter in their zip code. A 2017 analysis of Phoenix-area district enrollment patterns found open enrollment transfer students outnumbering charter students. More recently, I had the opportunity to revise the 2001 Manhattan Institute ranking with the author of the original study and two colleagues from the University of Arkansas. Arizona ranked first again in overall education freedom.

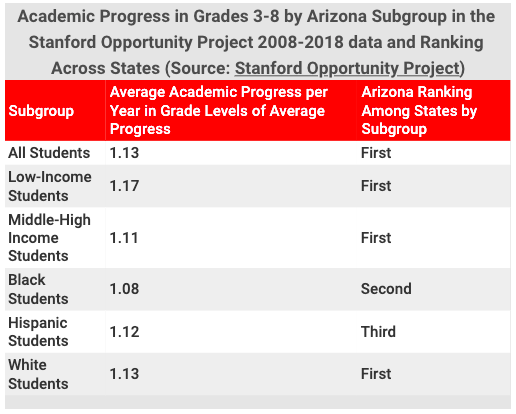

The University of Arkansas’s statistical analysis of state academic data found a positive and statistically significant relationship between additional K-12 options for parents and improved student academic performance. Separately from these efforts, Stanford University’s Opportunity Project linked state achievement data from across the country, allowing comparisons of academic proficiency and growth for schools, districts and the charters operating within them, counties and states as a whole. The project recently released new data including the 2017-18 school year, and there was again good news for Arizona. The state led the nation in student growth overall, and for growth among low-income students.

Maricopa County (the Phoenix metro area) likewise had the highest rate of academic growth both overall and for low-income students among large urban counties nationwide. What can the rest of the country take from the Arizona experience?

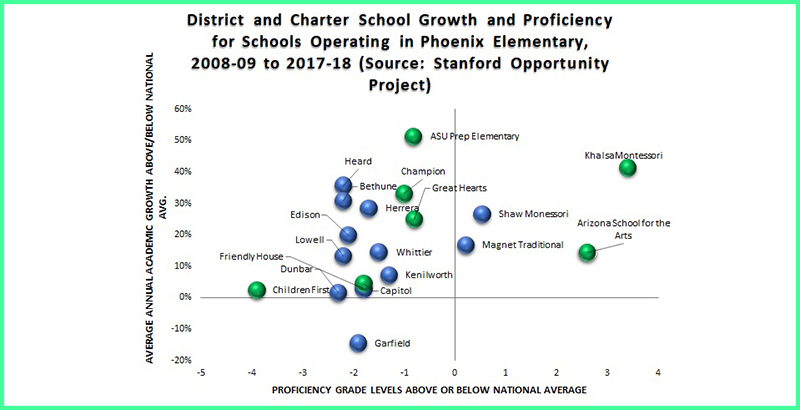

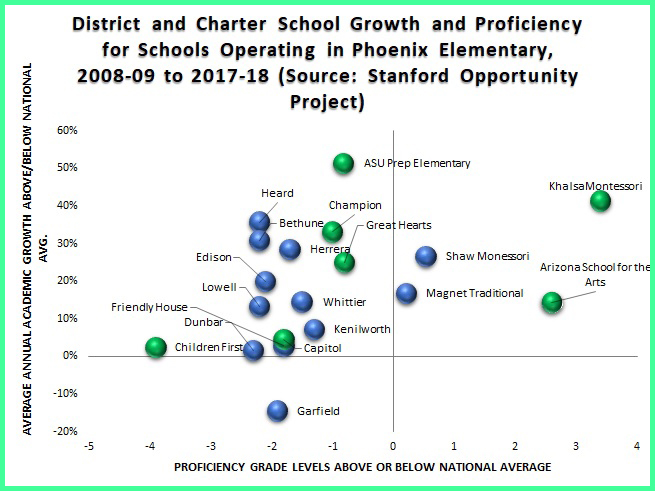

A closer look at school-level Stanford data in the Phoenix Elementary District shows how this is happening. It turns out downtown Phoenix has even a higher rate of academic growth than the state as a whole, and this was true in both district and charter schools, which give students in downtown Phoenix a wide variety to choose from.

Students attending the Phoenix Elementary district and the charter schools operating within the district’s boundaries are more than 90 percent non-Anglo, and 78 percent qualify for free or reduced-price school lunch. Yet their average academic growth rate for low-income students was 27 percent higher than the national average; for Arizona’s low-income students overall, it was 19 percent higher. To give some perspective: The Stanford data shows Orleans Parish — the much-celebrated (and rightfully so) portfolio district — has an average growth rate 10 percent higher than the national average during the period studied.

A caveat before proceeding: The Stanford data represent a snapshot in time between 2008 and 2018 and may not reflect recent trends. Still, when you examine the individual district and charter schools, two big things jump out — high rates of academic growth and the huge diversity of approaches.

Stanford defines the horizontal zero line above as “learned one grade level per year.” If your school is at the zero line, your students are making progress, but on average you won’t be closing deficits. Downtown Phoenix has a whole lot of district and charter schools closing deficits.

Next, notice the variety of school models. Both the district and a charter school offer a Montessori model (and both show strong academic growth). There are two schools focused on the arts (one did not appear in the chart due to missing data) operating in the boundaries of Phoenix Elementary. Students had access to one classical and one traditional education school, one district and one charter during this period. Students also had access to a charter school sponsored by Arizona State University. While opponents have long charged that letting families choose their children’s school would harm public school performance, neither Phoenix Elementary nor Arizona more broadly square with this assertion. Rather than withering, district schools in Arizona show high levels of academic growth.

Some of these schools draw students from far and wide. My trumpet-playing son, for example, graduated from the Arizona School for the Arts and is now studying mechanical engineering in college, but we never lived in the area. He had classmates from the area, but others from across the Phoenix metropolitan area. All the more reason to focus on the high levels of growth.

The district and charter schools in downtown Phoenix both strongly contribute to these high levels. Neither sector did it on its own, and families in the area are fortunate to have so many high-quality options to select from. The story here isn’t about district versus charter, but rather about students’ needs and the ability of families to choose a school that is a good fit for those needs.

A bipartisan group of Republicans and Hispanic Democrats set this in motion in 1994 by passing a robust charter law and forbidding districts from charging tuition for open enrollment. Arizona’s charter sector grew steadily, and when the Great Recession hit, charter operators with revealed demand in the form of waitlists took the opportunity to serve more students by acquiring inexpensive property.

The growth of this diverse and geographically inclusive charter sector increased incentive for districts to participate in open enrollment as well. About 20 percent of enrollment in the Scottsdale Unified School District comes from out-of-district transfers, demonstrating that a key to moving the needle for disadvantaged students lies not in focusing on a particular type of school model or community to the exclusion of other, but in transforming suburban districts from islands of privilege to active players in a system of choice.

As this improvement did not happen within the confines of a randomized study, any number of factors could have influenced the trend both positively and negatively. Arizona, however, suffered some of the largest Great Recession per-pupil funding cuts during the period covered by the Stanford data and transitioned from a small predominantly Anglo K-12 population in the early 1990s to a much larger and majority-minority student body. The state’s NAEP data shows broad improvement across student subgroups over time and higher overall performance. These trends sit comfortably with a thesis of choice benefits.

“Diversity. Pluralism. Variety,” progressive icon Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote in 1978. “We cherish these values, and I do not believe it excessive to ask that that they be embodied in our national policies for American education.” Milton Friedman, a Moynihan contemporary from an opposing intellectual tradition, noted, “A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both.” Arizona’s choice system has been proving out both of these statements for the benefit of families.

Correction: The Stanford data begins in 2008.

Dr. Matthew Ladner is director of the Arizona Center for Student Opportunity at the Arizona Charter School Association and executive editor of the weblog RedefinED. Previously, he served as a senior research fellow at the Charles Koch Institute and senior adviser for research and policy at Excel in Ed.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)