An Educator’s View: Stop Making Students Pawns in a Political Game They Didn’t Sign Up to Play

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Fifty-five years ago, my parents founded a little school in a three-bedroom house because my mother, a school teacher, had grown tired of feeling like children who looked like us were being left behind. She was tired of feeling like no one in the school seemed to notice or care or feel any sense of urgency around helping Black students in our Houston neighborhood.

In the beginning, she taught, cooked and cleaned while my dad opened and closed the school and maintained the business office. Lenders wouldn’t loan to Black businesses at the time, so my parents poured their own money into the school, and into the families. But they kept at it, motivated by the results my mom was seeing. Celebrating students’ achievements was becoming addictive, and she was witnessing children who came in below grade level beginning to attain test results that placed them several grades ahead. They were learning — and not only that, there was someone who actually cared for them, and cared about their outcomes.

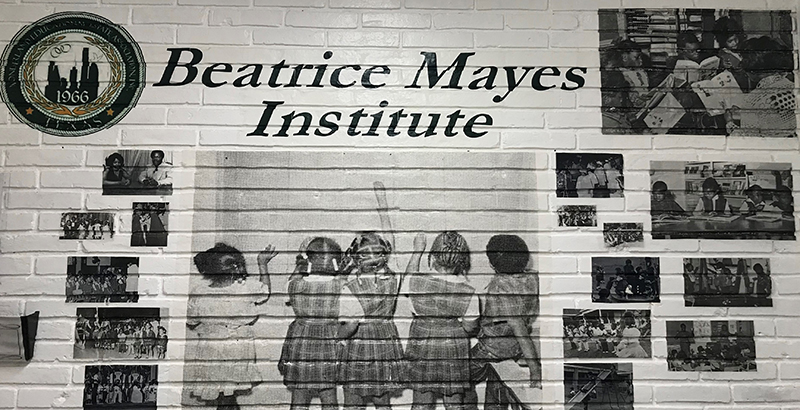

My mom often says the children became her heart, but she also has a heart for the families. Many of the parents who have come through our schools over the last 55 years had felt trapped in their local schools. But once they came to Wonderland Private School, and later Beatrice Mayes Institute, they felt safe. They knew that their children were being taken care of, and learning.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about my parents’ legacy, and my responsibility as the current superintendent of Beatrice Mayes Institute to continue the work of educating and caring for children others may be content to leave behind. I think about how far we’ve come as an education system over the last 55 years, but also about how much work there is left to do.

Gaps still persist in educational outcomes, in school discipline outcomes, in the academic opportunities presented to Black and brown children in this country. Schools that serve predominantly Black and brown populations still receive significantly less funding than schools that serve majority white populations, and that funding still comes with significantly more restrictions about how it is to be used.

I find myself increasingly frustrated that students — Black and brown and low-income children — seem to have become pawns in a political game they didn’t sign up to play. A finite and too-small pool of education resources has pitted districts and charter schools against each other to compete for funding, when we should be working together for the benefit of the students we serve. In sports, the moment a team becomes divided, it loses the game. The same is true in education. As long as we fight against each other, there will be Black and brown children who can’t read and graduate from high school unprepared for the next step.

If a child leaves my school and goes to a traditional district school, and that child is prepared for the next stage of his or her academic career, I’m excited that I’ve had the opportunity to move that student along Point A to Point B. I’m not attacking the district for stealing my per-pupil funding. It’s easy to lose sight of our shared goal of educating students, especially tough in the midst of a legislative session in Texas marked by trepidation over already too-low school funding being potentially reduced even more, thanks to the impact of a global pandemic on our economy. But it’s important to remember why we got into this work: We are in the human development business, and our students’ humanity has to remain at the center.

For too long, school funding has followed a trickle-down model. We plan for the top and expect those at the bottom to benefit. The students at schools with the highest family income bases often get the highest standardized test scores, and thus are rewarded with more funding, while the others are left to scrape and fight at the bottom of the barrel. But we know this doesn’t work. Trickle-down economics don’t work. We should be funding more at the bottom, knowing that if the students who have traditionally had the least are successful, those at the top will also succeed.

Fifty-five years after my parents founded this school and 57 years after Brown vs. Board of Education, the needle has not moved much at all on Black student achievement. In the moment we are in, one in which businesses and governments are declaring that Black lives matter and painting the slogan on their streets, it is time for us to show that Black students matter — and not just for the dollars they bring in via their per-pupil funding. We cannot give lip service to these students and these families only long enough to get them in the door, and then continue to let them fail once they are inside our doors, and then blame them for their failure. We have to remind ourselves that we got into this for the students and treat all students as if they were our own children, not pawns in our political processes.

Christopher D. Mayes is superintendent of the Beatrice Mayes Institute, a K-8 charter school in Houston.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)