An Early Education Rebound: After COVID Disruptions, Report Shows Pre-K Enrollment Hitting Record Levels

NIEER’s new preschool ‘Yearbook’ reveals record pre-k levels for the 2022 school year, with Mississippi & New Mexico among the top states making gains

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Four-year-olds entering pre-K in Mississippi’s Lamar County Schools don’t spend their days on worksheets or bent over papers practicing their letters. But they do have plenty of books, Play-Doh and time for friends.

And some leave for kindergarten knowing how to read.

“But it’s not because we’re hounding them,” said Heather Lyons, the program’s coordinator. “It’s because we’re constantly trying to help them pursue this love of learning.”

That careful mix of academics and social skills is one reason demand for the program is strong. Parents start calling in January to ask about registering their kids for the fall, Lyons said. Lamar’s program is part a statewide pre-K initiative now serving a quarter of the state’s 4-year-olds — up from about 3% six years ago.

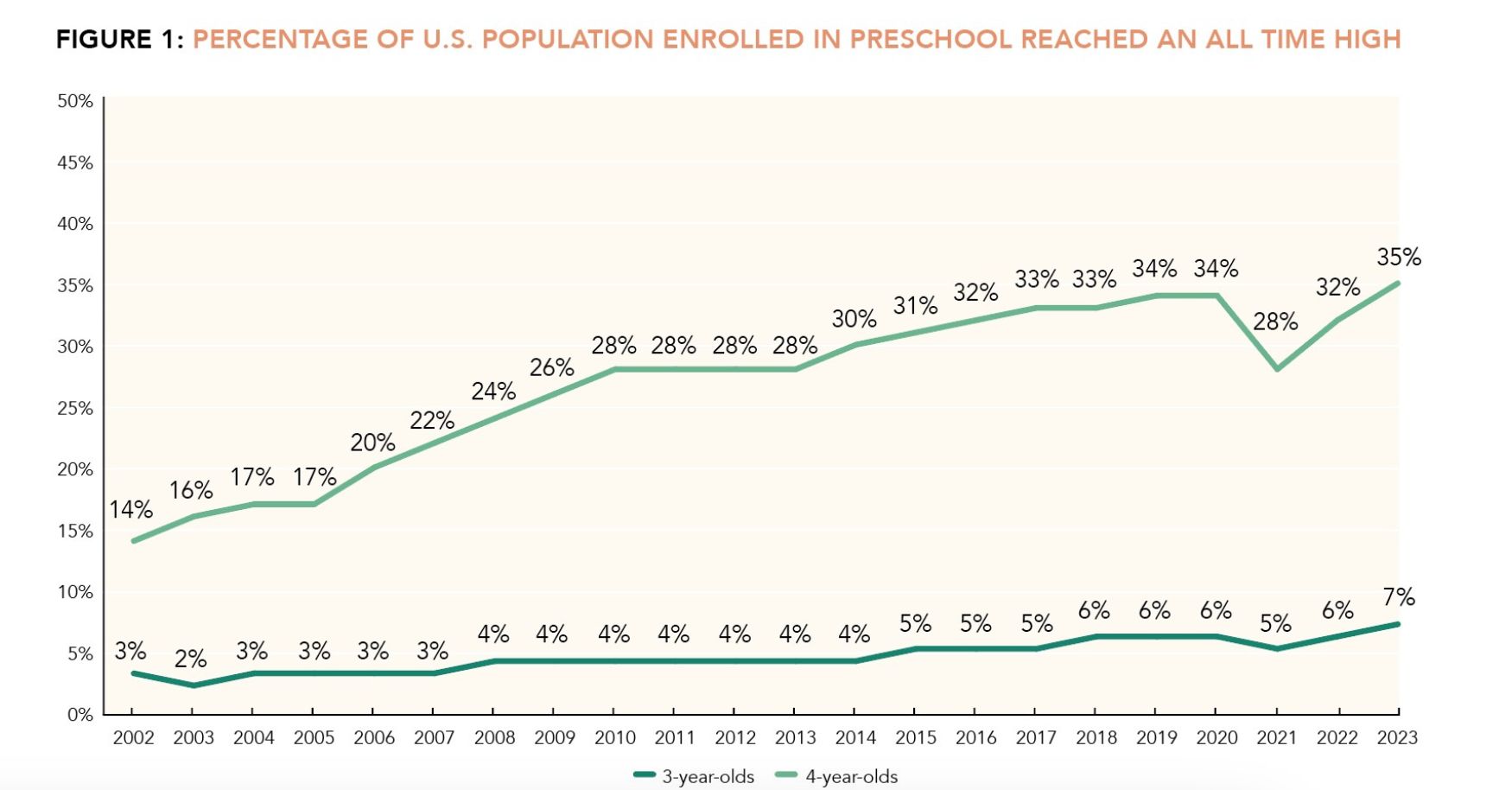

The state helped drive pre-K enrollment nationwide to record levels in 2022-23, according to the recent State of Preschool Yearbook from the National Institute for Early Education Research. Following sharp declines during the pandemic, participation in preschool is back on the upswing. Over 1.6 million children attended public pre-K last school year, with the percentage of 3-and 4-year-olds hitting new highs.

Expanding access, however, doesn’t mean states have to cut back on quality by lowering training requirements for teachers or increasing class sizes, the report’s authors note.

They point to Mississippi as an example of a state that’s managed to boost enrollment while maintaining high standards.

In fact, the state is among the few that have written the institute’s “quality benchmarks” into law. Those include having teachers with a bachelor’s degree, assistants with early-childhood training, and screenings for vision, hearing and health problems.

“We’re keeping an eye on them,” said Allison Friedman-Krauss, an assistant research professor at the institute. “They started small with a focus on quality. They are also working hard to fund more coaches to support teachers, so they’re committed to quality in that way.”

There are now 36 early learning collaboratives — local partnerships that include school districts, Head Start providers and child care centers — that offer the pre-K program.

“We’re moving out of the baby stage and into the teen stage of the law,” said Rachel Canter, executive director Mississippi First, an advocacy group. She added that including Head Start, the federal preschool program serving children in poverty, is one reason the program receives bipartisan support. “People across the political spectrum see how it can benefit their own community. That has allowed us to expand it statewide while also making sure kids who need it most are getting access.”

Due partly to her advocacy, the legislature has increased annual spending on the program five times since 2016.

Now the challenge is to increase the number of child care providers that participate and continue to expand, she said.

In communities without a program, parents are often left with lower-quality options or end up juggling their child between multiple caregivers during the day. Other parents, Canter said, might take fewer hours at work to stay home with their children. “That’s a terrible situation for a working family.”

Supporting the workforce

Advocates and policymakers are often the forces behind efforts to expand early-childhood education. But in New Mexico — another state making major moves in pre-K — it was the voters who demanded more access when they passed a 2022 ballot initiative by an overwhelming 73%.

The law creates permanent funding for early learning, resulting in the legislature appropriating $100 million for preschool last year. School districts, child care providers and tribal governments are now using some of those funds to strengthen the program by boosting teacher pay to match what K-12 teachers receive, using high-quality curriculum and giving preschoolers an extended school day.

The state also provides scholarships for teachers still earning their degree and pays for substitutes so teachers can take time off to attend courses.

“The early childhood workforce has just been historically undervalued,” said Sara Mickelson, deputy secretary of the state’s Early Childhood Education and Care Department. “We’re really a state that is supporting access to degrees.”

Meanwhile, 70% of New Mexico 4-year-olds now attend public preschool, making the state one of just a handful that serves at least two-thirds of eligible students.

But states serving the most preschoolers — like California, Florida and Texas — are not always examples of high quality.

California spent over $830 million in 2022-23 on preschool and is moving toward making all 4-year-olds eligible for its transitional kindergarten program by the fall of 2025. That figure accounted for over 70% of the total $1.17 billion increase in spending for the whole country, said Steve Barnett, the institute’s senior co-director.

But since it began a decade ago, the transitional program has met only a few of the institute’s 10 quality indicators. Teachers weren’t required to have special training in educating young children and class sizes were far larger than recommended — as high as 33 students, compared with the institute’s benchmark of 20.

“There were no guidelines from the state,” said Rahele Arakabi, director of educational services for the Washington Unified School District in West Sacramento. Classrooms, she said, looked more like first grade than pre-K, with students sitting in rows facing the whiteboard. “Teachers really were in that mode of drill and kill.”

But the outlook for the program has improved. Statewide, class sizes are now capped at 24 students with two teachers; districts and charters that don’t comply face fines. By the 2025-26 school year, ratios will be set at the institute’s standard of 10-to-1. The state also offers a new credential for educators teaching preschool through third grade, and by next year, teachers will be required to have college training or experience in early-childhood education.

In Washington Unified, which serves 130 transitional kindergarten students in six classes, ratios are even lower, 8-to-1. Some teachers who worked in the district’s separate preschool program have already earned a credential to teach in transitional kindergarten.

Arakabi used a $400,000 state grant to make classrooms more child-friendly, with age-appropriate furniture and play areas. She implemented a new curriculum specifically for pre-K and provided a year of coaching and support on child development. The investment, she said, is making a difference.

“My worry was always buying curriculum and then it just sits there in the shrink wrap,” she said. “This group of teachers is not easy to please, but they’re actually using it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)