Pre-K Enrollment Nearly Bounces Back From Pandemic Amid Push for Universal Access

But in its 20th year, the annual preschool ‘yearbook’ shows stalled efforts to improve quality

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The nation’s public pre-K programs saw a rebound last year as enrollment nearly reached pre-pandemic levels, new data shows.

Thirty-two percent of 4-year-olds attended a state-funded program in the 2021-22 school year — up from 28% the year before, when the National Institute for Early Education Research, which publishes the annual “yearbook,” reported that COVID had “erased” a decade of growth in public pre-K.

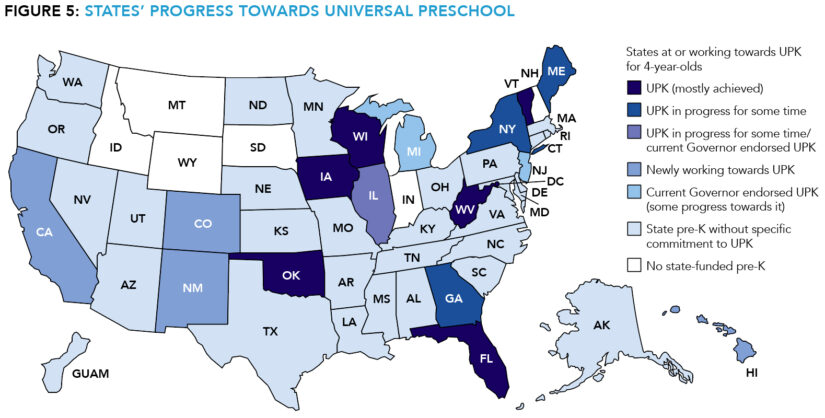

A recent push in several states to expand universal pre-K, meanwhile, could more than make up for that decline in the coming years, said Steven Barnett, founder and senior co-director of the research center based at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

California, Colorado, Hawaii and New Mexico recently passed laws to provide universal access to early-childhood education while governors in Michigan, Illinois and New Jersey have all taken initial steps in that direction.

“I don’t think we’ve had a wave like this. That dramatically changes the landscape,” Barnett said. Georgia was the first state to launch a universal pre-K program in 1992, followed by Oklahoma in 1998, but Barnett said, “That’s in the distant past.”

The institute’s latest report — its 20th — provides some perspective on how far states have come since researchers began tracking the data in 2001. Forty-five states now have publicly funded pre-K programs, seven more than when the institute issued its first report. The percentage of 4-year-olds served and the overall amount states are spending on pre-K has more than doubled.

But in some areas, there’s been little change. Taking inflation into account, average per-child spending has been relatively flat. And states only serve 6% of 3-year-olds. In New York City, where former Mayor Bill de Blasio aimed to make pre-K for 3-year-olds universal, his successor Eric Adams has eliminated the expansion from the city’s budget, citing the expiration of pandemic relief funds.

While overall state spending increased to nearly $10 billion, about $400 million of that was in COVID relief funding. Barnett, however, said he doesn’t expect states to cut funding when the funds run out because most of the expansion nationwide stems from voter-approved initiatives.

“Florida voters amended their constitution. That’s why they have universal pre-K,” he said during a call with reporters Wednesday. “At the local level, cities all over the country have taken it on themselves.”

The Biden administration is also urging districts to spend more of their Title I funds on pre-K and has proposed a $500 million grant program in the 2024 budget to expand pre-K in Title I schools.

While more states are adding universal pre-K, Barnett doesn’t see the same emphasis on improving quality. During the pandemic, several states paused efforts to strengthen programs and widely granted waivers from certain staff training requirements because of teacher shortages.

Delaware, for example, hasn’t yet reinstated classroom observations to help teachers improve, and North Carolina stopped limiting long-term substitutes to 12 weeks a year, according to the report. Substitutes are required to have an associate’s degree, but not a bachelor’s.

By noting these exceptions, Barnett said he hopes the report will “encourage states to not make this leniency permanent.”

Five states — Alabama, Hawaii, Michigan, Mississippi and Rhode Island — meet all 10 of the institute’s quality standards, the same as last year. Among the indicators are a strong curriculum that includes literacy and math, teachers with at least a B.A. and a staff-child ratio of 1 to 10.

Eleven states meet fewer than half of the standards, including three that serve the largest number of children: California, Florida and Texas.

Polis calls parents

California’s existing state preschool program for low-income children has been in place since 2008. The state then launched transitional kindergarten in 2012, but it was originally available only to 4-year-olds with fall birthdays who missed the state’s Sept. 1 kindergarten eligibility date. The state is now gradually expanding the program, which will be open to all 4-year-olds by the 2025-26 school year.

A state report shows enrollment in transitional kindergarten this school year fell well below projections, but that wasn’t the case everywhere. The Oxnard School District in Ventura County, up the coast from Los Angeles, expanded its program to younger students ahead of the state’s timeline. Leaders planned for nine classes and ended up having to open 25 due to demand.

“California will have the largest preschool program for 4-year-olds in the U.S.,” Patricia Lozano, executive director of Early Edge California, an advocacy organization, said during the press call.

Even though K-12 enrollment in California and several other states is declining, Barnett said that’s actually a boon for early childhood programs because states can serve more preschoolers without having to increase spending.

In Colorado, voters in 2020 approved a nicotine tax to fund universal pre-K, and last year Gov. Jared Polis, a Democrat, signed legislation creating the program, which will provide up to $4,300 per child annually.

He’s also been reaching out to families who secured a spot this fall. He called Mitchell Smith of Colorado Springs about two weeks ago to congratulate him on getting his first choice school for his daughter Arrow.

“I was blown away,” said Smith, a high school science teacher who also has a daughter in kindergarten. “Monday through Friday, [Arrow] sees her sister go to school. She wants to know, ‘When am I going to go?’”

Allie Caracillo, another Colorado parent, will be able to keep her daughter Giovanna in the KinderCare center that she already attends in Denver. But now the state-funded pre-K program will cover 15 hours a week.

“It was a no-brainer,” she said. She thinks she’ll be able to save several hundred dollars a week.

‘We’ve got a model’

In New Jersey, Gov. Phil Murphy is allocating $120 million in federal relief funds toward preschool facilities and expanding classes to more districts as part of his pledge to phase in a universal system. The model will expand on the state’s Abbott Preschool Program — mandated by the state supreme court in 1998 as a remedy to longstanding inequities in the state’s poorest school districts.

Barnett, who is involved in planning the program’s expansion, urged leaders not to cut back on components that have contributed to positive gains for students, such as class sizes of 15 with a teacher and an aide. A long-running evaluation showed that two years of attendance reduced half of the achievement gap between low-income children and those from more affluent families.

“We’ve got a model. We know it works. Let’s just do it,” Barnett said.

He predicts lawmakers without plans to offer universal access will likely feel pressure from neighboring states.

“If you’re a legislator in Oregon and Washington,” he said, “and California has universal pre-K, do you just say, ‘That’s nice, but we’re not going to do it’?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)