‘Already in the Door’: How One California Charter Network is Recruiting Staff as Special Education Teachers with Free Credentialing, Mentorship, and Better Salaries

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As schools nationwide scramble to hire special education teachers after a pandemic-exacerbated shortage, a California charter network is turning to existing staff to fill classroom slots by paying for costly credential programs, boosting salaries, and providing mentors.

“I’ve seen this across systems, not just Aspire, where we have these great educators in our schools, who just need support in accessing credential programs,” said Aspire Charter Schools senior special education director Lisa Freccero. “They’re invested in our schools; they want to work with our kids; they want to work in special education.”

All but two states reported special education teacher shortages for the 2021-22 school year. With declines growing for years, states have rolled out cash incentives to retain and recruit more special needs teachers in recent months.

Facing similar vacancies, Aspire is acting fast to scale up their small grow-your-own program. So far, seven educators across their network of 36 California sites have participated.

Now in its third year, Aspire’s Education Specialist Intern Sponsorship program creates a pipeline of school volunteers and classroom aides “already in the door,” Freccero said, providing a pathway for uncredentialed staff, predominantly Black and Latino adults — who also reflect the network’s 15,000 students — to stay with the school community.

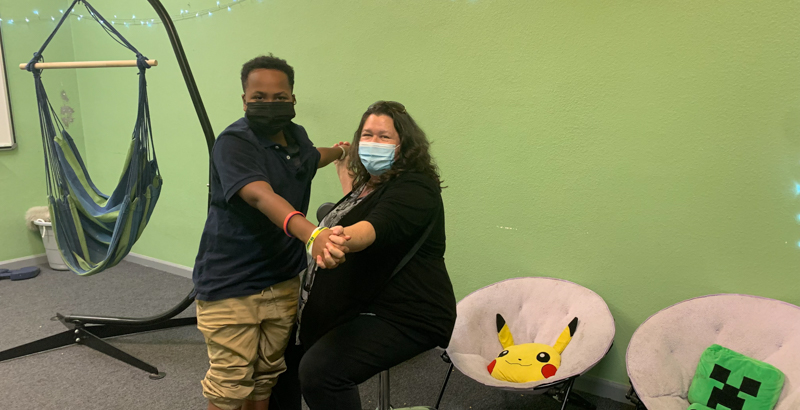

Aspire staff are hired on as first year teachers at a salary of $56-59,000. Through one-on-one coaching with administrators — including feedback from senior teachers on recorded lessons — specialist interns learn by doing, applying strategies with students in real time, with daily guidance from their senior mentor.

Even before the pandemic, Aspire’s Bay Area and Central Valley schools had persistent staff vacancies in special education. The last year saw specialist vacancies grow in their Los Angeles schools, where the Sponsorship program is now being expanded.

One East Oakland site is operating with three full-time special education aides, about half of their usual team of five to six. Their Bay Area schools have the highest shortages, currently filled by contractors or substitutes, though all regions have vacancies in every special education role — from speech pathologists and specialists/teachers to school psychologists.

“It’s a high turnover profession… We were trying to solve for that,” Freccero added. “When we talk to them, for the vast majority, [the] barrier was having to either stop their current job or simultaneously figure out a way to pay to go back to school and do a credential program.”

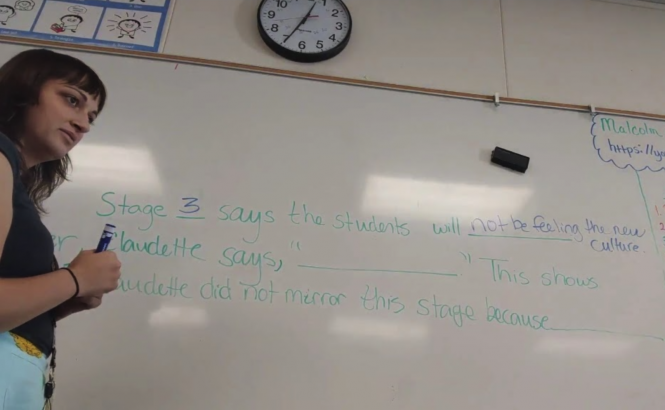

Michelle Ciraulo, a teacher in one of Aspire’s 36 schools in East Oakland, was planning to do just that: save up at least $10,000, while working full-time, to enroll in a credential program. If certified, she’d have a better chance of staying with her caseload of 10th- and 11th-graders and earn higher wages.

“The cost was a hindrance. I wanted to become an ed specialist next year, but I would have probably ended up having to do that with an emergency certification, which you can only do for one year,” she said. “[This] definitely sped up the process.”

Ciraulo said she is also more in tune with general education teachers who she partners with in an inclusion class. Students with IEPs are assisted in general education classrooms.

The connection between teachers is necessary, she said, to make stronger lesson plans and better support students. The program enabled her to form deeper connections with students, too.

“It was really a big incentive for me to just become a specialist but also to stay at this school site and continue to work with my kids and get to know them really well — and their families,” Ciraulo said.

Colleagues say that the model can also help prevent burnout many career educators experience around their fifth year. After juggling student caseloads, paperwork and learning to teach — often with little feedback or support networks — many feel overwhelmed from year one. Aspire’s model cuts down on learning curves via multiple mentors and gradually-increasing caseloads.

“Where do you think we should go next … What data do you want? What data do you need? What assessment should you use? … It takes a while to get that knowledge,” senior special education teacher Suzanne Williams said. “When you already have somebody right there next to you who has that knowledge, it’s beautiful, and it benefits the students the most.”

A parent of students with disabilities who started out as a volunteer in her childrens’ schools, Williams added that the first three years are typically the hardest for new teachers she’s witnessed in Modesto, a small city southeast of San Francisco. Williams said her mentee Stephanie’s first years were a success because of the Aspire model.

“She didn’t have to guess — she had somebody right there to ask. When she was writing her lesson plan, she was actually writing lesson plans that she was using each and every day […] She was all in 100% from the get go. We gave her a light caseload and then she worked her way up,” Williams said.

Stephanie would record general education teachers’ classes and her own instruction, and the three educators would pour over them in detail, providing and adapting to feedback. And in built-in “dry runs,” Williams roleplayed students as Stephanie practiced lessons.

The mentorship took out the guesswork that typically comes with being the only, or one few, special education specialists at a site. By the end of the one-year program, Williams said it felt like her mentee had gained three years of experience.

“She’s not focusing on all the things she needs to learn and needs to be. She already has that mentor right there, working hand in hand […] The person is going into that situation prepared or feeling confident,” Williams told The 74. “A confident teacher brings confidence to the students.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)